Global| Feb 06 2019

Global| Feb 06 2019A New Working Theory of Inflation

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

It has long been observed that inflation is a monetary phenomenon. The foundation for this observation was developed decades ago when accelerating and decelerating rates of consumer price inflation were associated with similar [...]

It has long been observed that inflation is a monetary phenomenon. The foundation for this observation was developed decades ago when accelerating and decelerating rates of consumer price inflation were associated with similar patterns of growth in money. Nowadays, the concept of money itself is under constant refinement, and money growth is no longer part of the Federal Reserve objectives, which raises an important question, is there a new working theory of inflation?

It has long been observed that inflation is a monetary phenomenon. The foundation for this observation was developed decades ago when accelerating and decelerating rates of consumer price inflation were associated with similar patterns of growth in money. Nowadays, the concept of money itself is under constant refinement, and money growth is no longer part of the Federal Reserve objectives, which raises an important question, is there a new working theory of inflation?

I raise this question for the simple reason that structural changes in the financial markets coupled with regime changes in the conduct of monetary policy have altered the transmission process of monetary policy in a way that inflation is no longer predictable based solely on money growth nor limited to the standard price measures.

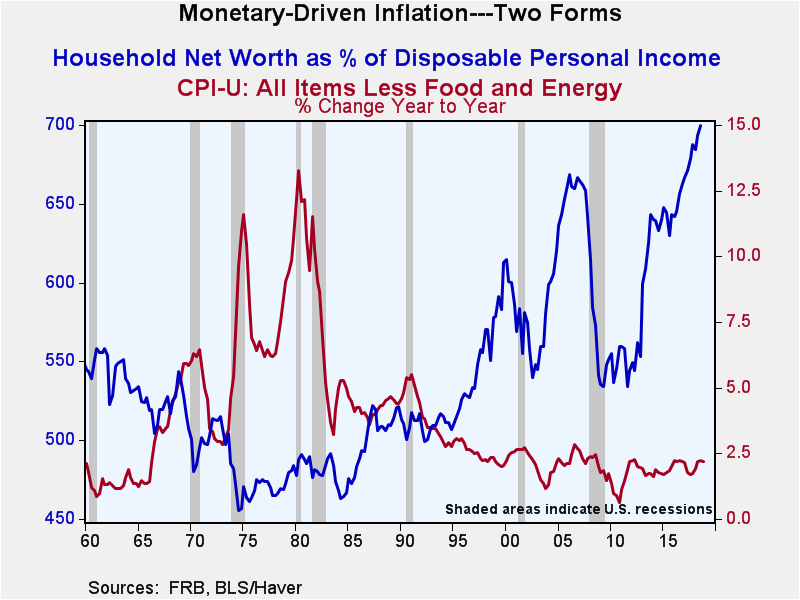

In the past several decades, the US has experienced two fundamentally different types of inflation (or price) cycles, with one associated with fast growth in money while the other form was not, and yet each cycle proved to be a monetary-driven event with similar outcomes.

For example, from the early 1960s to the early 1980s the US economy experienced successive periods of relatively fast gains in consumer prices and all were associated (fueled) with fast gains in money. And, from the mid-1990s to today, the US economy has experienced consecutive cycles of unprecedented gains in asset inflation, fueled by relatively low interest rates, easy credit conditions assisted in part by growth of non-bank banks, and more recently with additional monetary accommodation via the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Although of a different form, the inflation (or price) cycles had a number of common characteristics. For example, all cycles proved to be persistent as each one had a self sustaining feature as the more and more prices rose it led to the expectations of more price gains, creating an inflationary (or speculation) mindset that was hard to break in the real economy or in the minds of investors. Also, inflation cycles created market distortions, such as allocating too much capital towards inflation-benefitting industries (i.e. commodities) or conversely sending too much capital towards asset-price benefiting industries (finance and housing). Yet the important common feature was that all inflation cycles ended with a bad outcome (recession); although the jury is still out on the current asset-price cycle.

Policymakers confront traditional inflation cycles because inflation feeds in part on itself, creating uncertainty and distortions in the economy and the flow of capital, depriving the economy of reaching its potential and eventually forcing a substantial tightening of financial conditions and a recession to unwind the destabilizing forces. Yet, asset inflation cycles also feeds in part on itself, triggering unbalanced capital flows, wealth inequality, ultimately leading to costly real and financial imbalances that eventually unravel driving the economy into recession.

If both forms of inflation cycles have like outcomes shouldn’t monetary policy view them similarly as they relate to the Fed’s mandates of financial stability, maximum employment and price stability?

Many questions remain unanswered, but perhaps the most important question has already been answered in that asset price inflation has become a new permanent feature of the transmission of monetary policy. Part of this is due to regime shifts in the conduct of monetary policy as policymakers moved from targeting money to targeting real interest rates (consumer prices less official rates) and now directly targeting consumer price indices. Real and financial asset prices are not part of the published prices so their price cycles have been able to run free of monetary oversight. Also, the new policy tool, the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet, is intended to work through the portfolio channel, directly lifting the price of a broad range of assets.

The new working theory of inflation is that it is still a monetary phenomenon but today’s inflation form is shaped by how monetary policy is implemented. The new targeting regimes has let the real cost of credit for real estate and equity purchases to remain too low for too long, driving fast asset price cycles. Admittedly, asset prices are determined by many factors other than monetary policy, but recent perceived shifts in monetary liquidity (first tighter and then looser) followed by abrupt declines and sharp reversals in equity prices illustrate how closely linked the asset price cycle is to expected shifts in the stance of monetary policy. Policymakers should not ignore these price signals as past asset price cycles have led to bad outcomes.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.