Global| Aug 19 2019

Global| Aug 19 2019Bilateral Trade Balances – Whack-A-Mole?

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

President Trump has imposed higher tariffs on U.S. imports from Mainland China, in part, to narrow the bilateral trade deficit that the U.S. runs with China. The president's tariff policy appears to be working. As shown in Chart 1, [...]

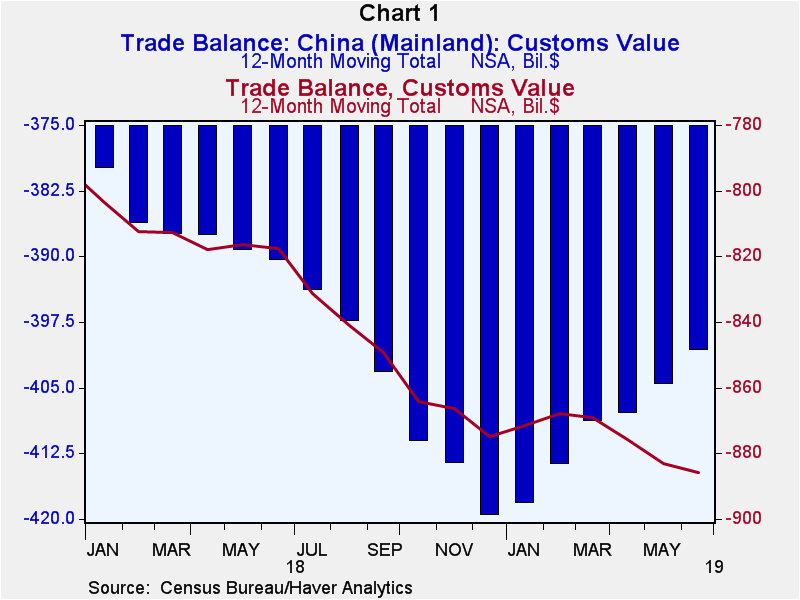

President Trump has imposed higher tariffs on U.S. imports from Mainland China, in part, to narrow the bilateral trade deficit that the U.S. runs with China. The president's tariff policy appears to be working. As shown in Chart 1, the 12-month cumulative U.S. trade deficit in goods with Mainland China (the blue bars) is narrowing. For example, after a reaching a record goods deficit of $419.5 billion in the 12 months ended December 2018, the U.S. goods deficit with Mainland China narrowed to $400.7 billion in 12 months ended June 2019.

President Trump has imposed higher tariffs on U.S. imports from Mainland China, in part, to narrow the bilateral trade deficit that the U.S. runs with China. The president's tariff policy appears to be working. As shown in Chart 1, the 12-month cumulative U.S. trade deficit in goods with Mainland China (the blue bars) is narrowing. For example, after a reaching a record goods deficit of $419.5 billion in the 12 months ended December 2018, the U.S. goods deficit with Mainland China narrowed to $400.7 billion in 12 months ended June 2019.

So far, so good for President Trump's desire to see the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China narrow. But, I think it is fair to say that the president believes that it is in the best interest of the U.S. to not only reduce our bilateral trade deficit with China but our trade deficit with the rest of the world as well. And here, things are not moving in President Trump's desired direction. Also shown in Chart 1 is the 12-month cumulative U.S. trade deficit in goods with the world (the red line). Although the U.S. bilateral goods trade deficit with China has been narrowing in recent months, the U.S. goods trade deficit with the world widened to a record $886.0 billion in the 12 months ended June 2019. This seems like a game of Whack-A-Mole. President Trump hikes tariffs on imports from one country in order to reduce the bilateral trade deficit with that country, and our trade deficits with other countries widen.

So, if President Trump wants to reduce our trade deficit with the rest of the world, should he increase tariffs on all imports, those from Afghanistan through Zimbabwe? In other words, why not whack all of the moles simultaneously? As I argued in a March 5, 2018 commentary entitled “The Expected Widening in the U.S. Federal Budget Deficit Has Trade Protectionist Implications”, fiscal policies that widen a country's government budget deficit can also cause the country's trade deficit to widen. (I suggest you read this March 5, 2018 commentary to get a more fully articulated explanation of the argument I am making in this current commentary.) If an individual spends more than they (please forgive me Ms. Mintz, my 6th grade grammar teacher, but this is the new convention for he or she) earn, then they must be either borrowing or selling assets. The same holds true for an economy. If the residents of an economy are collectively spending more than they are producing, the economy must be running a trade deficit, which is being financed by borrowing from and/or selling assets to the rest of the world. If an increase in a government's fiscal deficit leads to an increase in aggregate spending on goods and services in the economy such that aggregate spending exceeds aggregate production of goods and services, the increase in the fiscal deficit will result in a widening of the country's trade deficit.

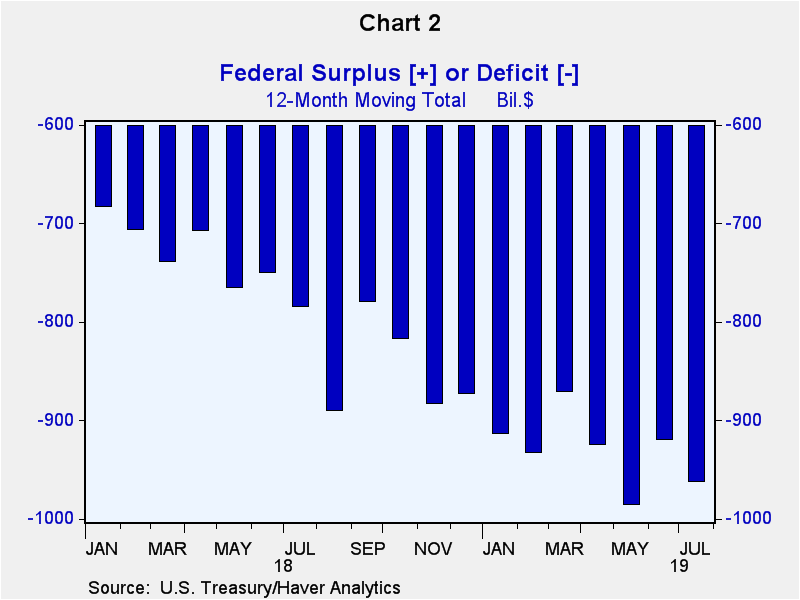

Chart 1 showed that the U.S. trade deficit in goods (the red line) has been widening of late. Chart 2 shows that the U.S. federal government's fiscal deficit also has been widening. In the 12 months ended July 2019, the U.S. federal government deficit was $962 billion compared with $683 billion in the 12 months ended January 2018.

Chart 1 showed that the U.S. trade deficit in goods (the red line) has been widening of late. Chart 2 shows that the U.S. federal government's fiscal deficit also has been widening. In the 12 months ended July 2019, the U.S. federal government deficit was $962 billion compared with $683 billion in the 12 months ended January 2018.

I believe that the widening in the U.S. federal budget deficit has contributed to an increase in aggregate spending in the U.S. economy compared to aggregate production and, therefore, the widening U.S. federal budget deficit has contributed to the widening U.S trade deficit. The implication of all this is that the imposition of higher tariffs on U.S. imports will not materially reduce the U.S. trade deficit so long as the U.S. government federal budget deficit continues to widen, which it is forecast to do. Imposing higher tariffs on imports to reduce a trade deficit while at the same time pursuing a fiscal policy that widens the government budget deficit is akin to chasing one's tail.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Paul L. Kasriel

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Mr. Kasriel is founder of Econtrarian, LLC, an economic-analysis consulting firm. Paul’s economic commentaries can be read on his blog, The Econtrarian. After 25 years of employment at The Northern Trust Company of Chicago, Paul retired from the chief economist position at the end of April 2012. Prior to joining The Northern Trust Company in August 1986, Paul was on the official staff of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago in the economic research department. Paul is a recipient of the annual Lawrence R. Klein award for the most accurate economic forecast over a four-year period among the approximately 50 participants in the Blue Chip Economic Indicators forecast survey. In January 2009, both The Wall Street Journal and Forbes cited Paul as one of the few economists who identified early on the formation of the housing bubble and the economic and financial market havoc that would ensue after the bubble inevitably burst. Under Paul’s leadership, The Northern Trust’s economic website was ranked in the top ten “most interesting” by The Wall Street Journal. Paul is the co-author of a book entitled Seven Indicators That Move Markets (McGraw-Hill, 2002). Paul resides on the beautiful peninsula of Door County, Wisconsin where he sails his salty 1967 Pearson Commander 26, sings in a community choir and struggles to learn how to play the bass guitar (actually the bass ukulele). Paul can be contacted by email at econtrarian@gmail.com or by telephone at 1-920-559-0375.