Global| Feb 22 2021

Global| Feb 22 2021Conversation With BLS About Price Mismeasurement For Housing

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

Recently, I shared my concerns about price mismeasurement for owner-occupied housing with a senior official who works in the Division of Consumer Prices at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The senior official agreed with me, [...]

Recently, I shared my concerns about price mismeasurement for owner-occupied housing with a senior official who works in the Division of Consumer Prices at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The senior official agreed with me, "That, in theory, treatment of owner-occupied housing in a CPI measure sounds easy, but in practice, it is not." Here's a summary of the main points of the conversation.

Recently, I shared my concerns about price mismeasurement for owner-occupied housing with a senior official who works in the Division of Consumer Prices at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The senior official agreed with me, "That, in theory, treatment of owner-occupied housing in a CPI measure sounds easy, but in practice, it is not." Here's a summary of the main points of the conversation.

First, the senior official noted the International Labor Organization (ILO) manual of Consumer Prices states: The treatment of owner-occupied housing in consumer price indices (CPIs) is arguably the most difficult issue faced by CPI compilers.

I used to share that view, but no longer. The most challenging problem in price measurement is the pervasiveness of item replacements. It isn't easy to get a continuous price series when products have a short shelf-life. Technology products create a problem for price measurement as the characteristics of items change frequently. The stock of housing does not change much from year to year, so it's not an issue.

Moreover, the quality of house price statistics has dramatically improved in the past few decades. Repeat sales series adjusted for the time between sales provides government statisticians with price information that was not available in the past. In the early 1980s, BLS cited poor data quality on house prices as one reason to change the measurement of owner housing costs. Nowadays, there is better data on prices for owner housing than there is for rents.

Second, according to ILO, "Depending on the proportion of the reference population that are owner-occupiers, the alternative conceptual treatments can have a significant impact on the CPI, affecting both weights and, at least, short-term measures of price change."

But the hard evidence shows that alternative measures have had a significant short-term and long-term influence on reported inflation.

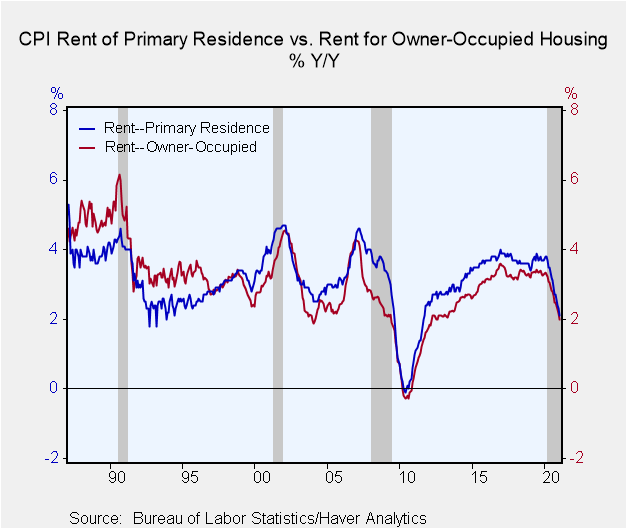

In 1999, BLS adopted an alternative measure for owner-occupied housing. Due to an inadequate sample of homes for rent, BLS decided to use rent data to gauge the owner-occupied housing implicit rents. Before the change, the rate of inflation for owner-occupied rent ran consistently above rent inflation. But after the change, that pattern flipped. Since 1999, the inflation rate for rent for primary residences has always run above what BLS estimated for owner-occupied housing.

That pattern of rents runs counter to market fundamentals. During periods of economic expansion, the vacancy rate for owner-occupied housing is falling, while the rental market's vacancy rate often moves in the opposite direction. Shrinking supply with rising prices for homes should yield a rent-inflation rate for owner-occupied housing that is much faster than the rent for a primary residence.

BLS data shows that the cumulative increase in rents for a primary residence is 20% greater than that of owners-occupied over the past two decades. It would seem improbable that based on market fundamentals alone, the owner's rent rate would run below that of primary rents.

The weight of owner-occupied housing accounts is substantial, accounting for approximately 30% of the core CPI. And given its vast scale, the continuous understatement of rent-inflation for owner-occupied housing has created the false impression that cyclical inflation is "flat". But in reality, it's not.

Third, the senior official stated that it is not "impossible" to measure owner-occupied implicit rents from rental markets. I said it is.

The two markets are separate. Research has shown that location is an essential factor for housing price, and it makes sense it would also influence rents. Owner housing is of a much higher quality than renter housing. Over 80% of owner homes are detached single-family versus less than 30% for rentals, and owner-occupied homes are much larger in scale. Five states, including two of the largest rental markets (New York and California), have rent control or rent stabilization policies. Trying to match the inflation rate from a partial-regulated rent market with one that is not regulated creates the potential for large-scale price mismeasurement.

Janet Norwood, the legendary BLS Commissioner, stated, "The goal of a government statistical agency must be to produce data that are objective, relevant, accurate, and timely." BLS measure of owners' housing costs fails all four.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.