Global| Nov 04 2019

Global| Nov 04 2019Fed's Insurance Rate Cuts Don't Eliminate Risks They Create New Ones

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

Preemptive policy moves have been a defining feature of monetary policy. In the past policymakers have made preemptive rate adjustments in response to potential inflation pressures, financial market turmoil, and now perceived risks [...]

Preemptive policy moves have been a defining feature of monetary policy. In the past policymakers have made preemptive rate adjustments in response to potential inflation pressures, financial market turmoil, and now perceived risks from trade disputes. The paradox in this approach is that taking out "insurance" against a perceived risk shifts monetary policy in a new direction creating the potential for other risks to develop. In the end, it's hard to prove that the economic outcomes are any different following a series of preemptive policy moves, but what are different are the timing and the imbalances that eventually ends the business cycle.

Fed's Insurance Cuts of 2019 & 1998

Although there is more than 20 years that separate the "insurance" cuts of 2019 and 1998 there are a lot of similarities.

For example, in 1998 policymakers was facing an economy that was not in any apparent need of monetary stimulus. The US economy was on a solid growth path, marked with the jobless rate of mid-4% at its the lowest since the late 1960s, core consumer price inflation in the mid-2% range and all of the broad equity markets at or near record highs. Based on domestic factors a number of policymakers thought official rates should be raised over the course of 1998.

Nonetheless, the double whammy of the Russian debt default and the follow-on default of a major hedge fund created the potential for major turmoil in the domestic and global financial markets. Even though the Fed thought there was a low-probability of these events derailing the US economy—and there was zero evidence of any impact in the hard data---policymakers cut official rates three times over the short span of six weeks from late September to mid-November.

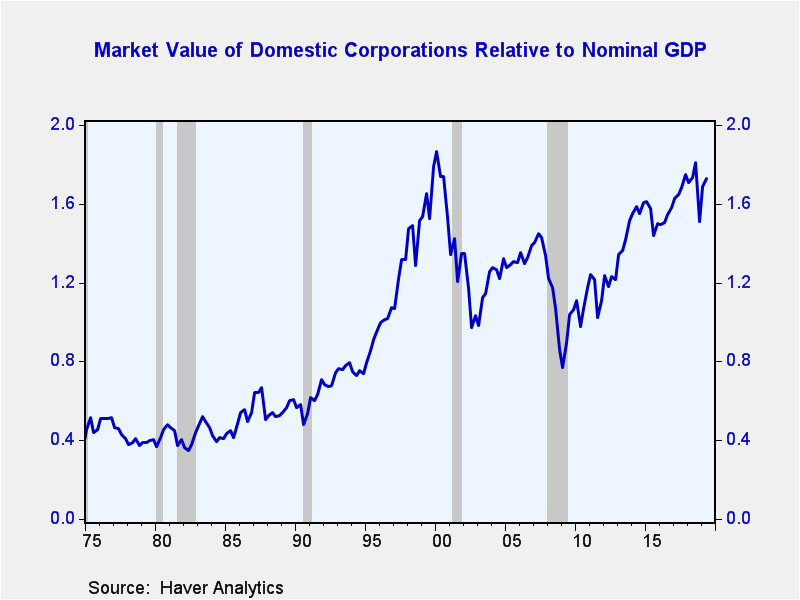

It is hard to say what would have happened to the economy had policymakers had not decided to lower official rates, but given the economy's strong performance—expanding nearly 6% annualized in the second half of 1998 –suggests strongly that the economy would have been fine without any policy adjustment. Nonetheless, most financial market participants are in agreement that adding monetary stimulus and not removing it until a year later helped fuel speculation in the financial markets, lifting the market valuation of domestic companies relative to nominal GDP to record levels only to end with a crash in equity prices and the economy in 2000 when profits failed to meet lofty expectations.

It is hard to say what would have happened to the economy had policymakers had not decided to lower official rates, but given the economy's strong performance—expanding nearly 6% annualized in the second half of 1998 –suggests strongly that the economy would have been fine without any policy adjustment. Nonetheless, most financial market participants are in agreement that adding monetary stimulus and not removing it until a year later helped fuel speculation in the financial markets, lifting the market valuation of domestic companies relative to nominal GDP to record levels only to end with a crash in equity prices and the economy in 2000 when profits failed to meet lofty expectations.

In 2019, policymakers started the year with the expectation that official rates should be raised. Yet the double whammy of a sharp sell-off in the financial markets and the potential hit to the economy from the trade dispute between China and US forced policymakers to hit the "pause" button on rate decisions.

Since mid-year, even though many viewed it to be a low-probability that the trade dispute would derail the US economy policymakers cut official rates three times. It's worth noting that today's economic and financial backdrop---the jobless rate of mid-3% at its lowest rate since the late 1960s, core consumer price inflation in the mid-2% range and all of the broad equity markets at or near all time highs---is very similar to that of 1998.

Policymakers are well aware of the fact that no level of official rates can help businesses overcome the uncertainty and the potential lost of markets from trade disputes. Yet, by easing policymakers are hoping other parts of the economy that are sensitive to interest rates---like segments of consumer spending and housing---can be stimulated enough to offset the drag from business spending. This policy decision comes with the "big" risk, as its adding monetary stimulus to a domestic economy that is not in apparent need of any, possibly fueling more speculation to already "hot" asset markets.

Is 2019 another 1998? There is one more similarity that should not be overlooked—the trend in company profits. Operating profits peaked in 1997 and continued to move lower over the course of the next three years, even though the economy and the equity markets did not peak until 2000. Operating profits peaked 5 years ago and despite the weakness in company profitability equity markets have continued to move higher, hitting new record highs in the process.

Will history repeat itself? By lowering official rates policymakers have extended the lifespan of the business cycle, similar to that of 1998's decision, but in doing so they probably also wrote the script for its ending. Once again, equity market gains—which have lifted the market valuation of domestic companies relative to nominal GDP to levels last seen in 1999/2000--- are linked to easy money and not stronger corporate profits. History sometimes repeats itself in the world of finance and in the economy---and odds are high it will again.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.