Global| May 04 2021

Global| May 04 2021Global Ripple Effects from US Policy Stimulus

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

Last week the Biden administration announced that it is contemplating a further major package of fiscal policy measures for the US economy. While the size of the package that is being touted caught the imagination of many observers it [...]

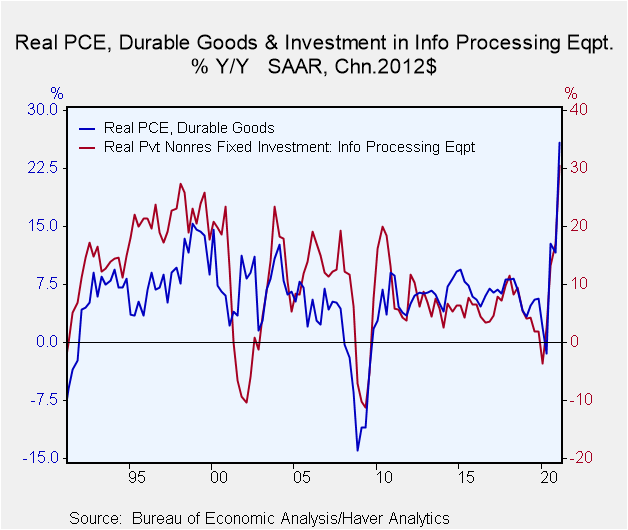

Last week the Biden administration announced that it is contemplating a further major package of fiscal policy measures for the US economy. While the size of the package that is being touted caught the imagination of many observers it was the timing - relative to the publication of Q1 US GDP data – and its underlying details – that was also noteworthy. The latter’s headlines centred on a 6.4% annualised gain in real GDP and a 10.7% gain in nominal GDP. The details though revealed that these impressive gains owed a great deal to a surge in both consumption of durable goods and in investment in information processing equipment (see figure 1 below). Indeed over half of the growth rate in US real GDP in Q1 can be traced to the additional spending from these two components.

Figure 1: US consumption of durable goods and investment in information processing equipment

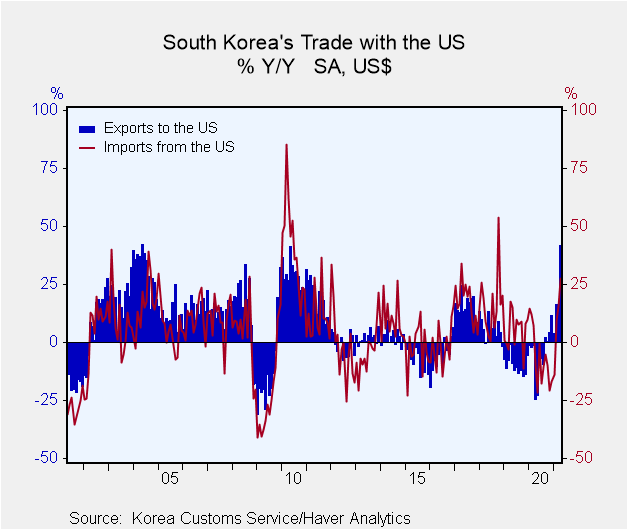

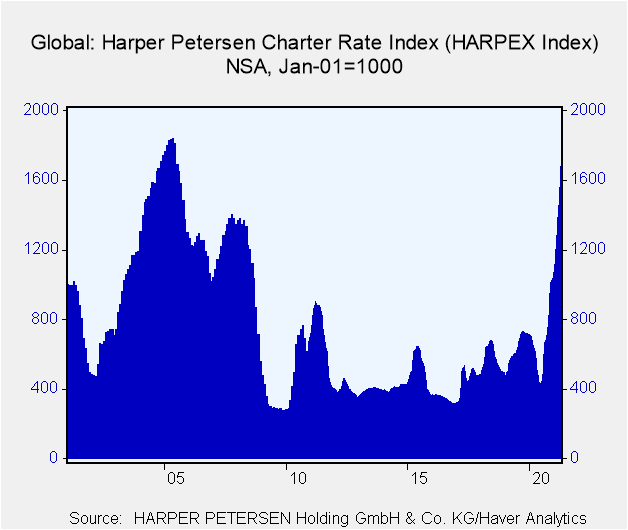

It is the global ramifications of this spending, however, where matters are arguably even more noteworthy. For this surge in US demand for goods and ICT equipment is generating some impressive ripple effects for some – though not all – parts of the rest of the world. Asia’s trade growth, for example, is soaring and in many respects because of firming US demand. South Korean exports – typically a great bellwether for Asia’s trade – climbed by 42% y/y in April (see figure 2 below) fuelled in large part by strong US import demand. China’s export volumes are estimated to have risen by 57% y/y in February while import values from the US were up 31% year-to-date in March. Rising prices for container ship leases and ocean freight rates relay a similar message about the heady pace of trade activity (see figure 3)

Figure 2: South Korean exports and imports from the US

Figure 3: Harper index of container ship prices

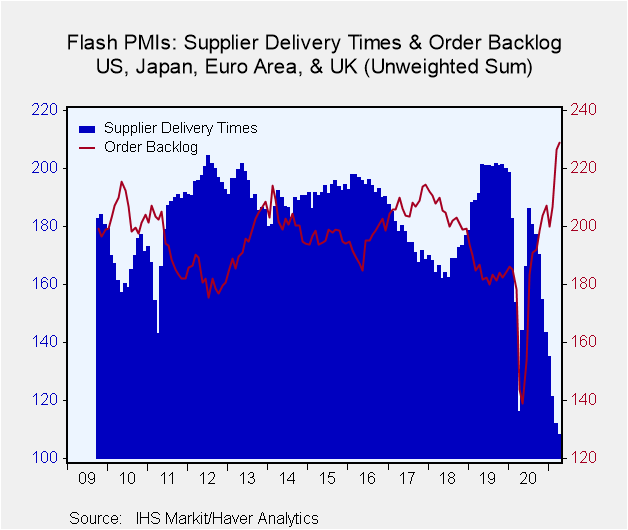

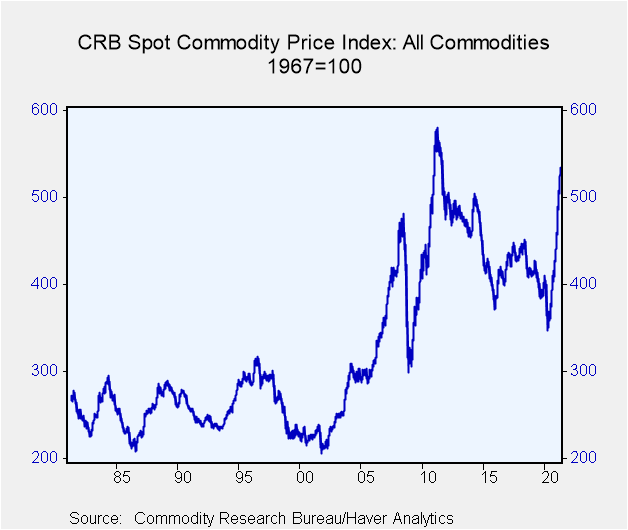

Another ripple effect of note against this buoyant demand backdrop concerns supply disruption. The US Census Bureau’s latest Small Business Pulse survey reveals increasing difficulties from delays in shipping and supply-chain bottlenecks. These problems moreover seem to be particularly acute for the wholesale and retail sectors. This chimes, moreover, with broader evidence from recent Purchasing Managers surveys. Average supplier delivery times for the US, Japan, Euro area and the UK lengthened to unprecedented levels in April (relative to the history of 12 year history of this survey) while order backlogs rose to unprecedented highs (see figure 4 below). And unsurprisingly against these demand and supply considerations commodity prices have been rising sharply (figure 5).

Figure 4: Flash PMIs: Supplier delivery times and order backlogs in the US, Japan, Euro area and UK

Figure 5: CRB Commodity Price Index

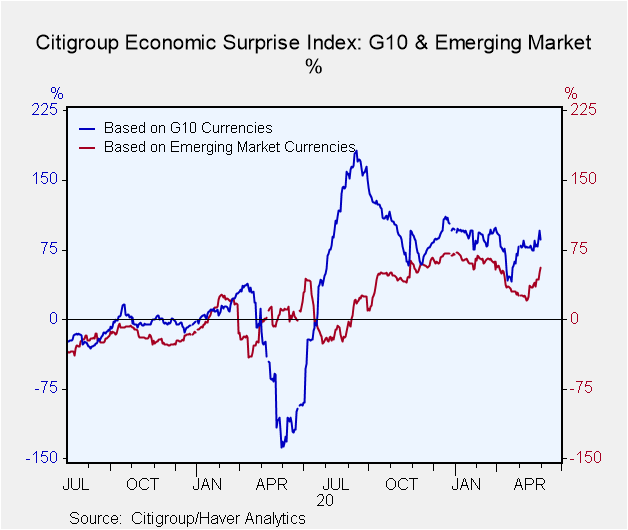

It’s also unsurprising – and with no pun intended – that surprise indicators for some emerging economies have been conveying a more buoyant picture of economic conditions (relative to expectations). Indeed incoming economic data have on the whole tended to beat consensus forecasts more frequently than in developed economies in the past several months (see figure 6). A number of factors are surely at play here including COVID considerations and China’s economic recovery. But a US policy-fuelled pick up in world trade and commodity prices have clearly been of some importance too.

Figure 6: Citigroup economic surprise index for emerging and G10 currencies

Of course, much of the above could be ephemeral and a function of a temporary shift in demand patterns that have been driven by US stimulus cheques and COVID-induced lockdowns. On the latter, a work-from-home tilt in demand for goods and technology products has been partly counter-balanced by much weaker demand for services (e.g. for restaurants, travel and tourism). We should note too that while economic data from emerging regions has - on the whole - tended to surprise positively, much less buoyancy is conveyed by trade indicators in areas such as Latin America and Eastern Europe. In other words Asia is the clear hot spot for trade in the emerging complex at present

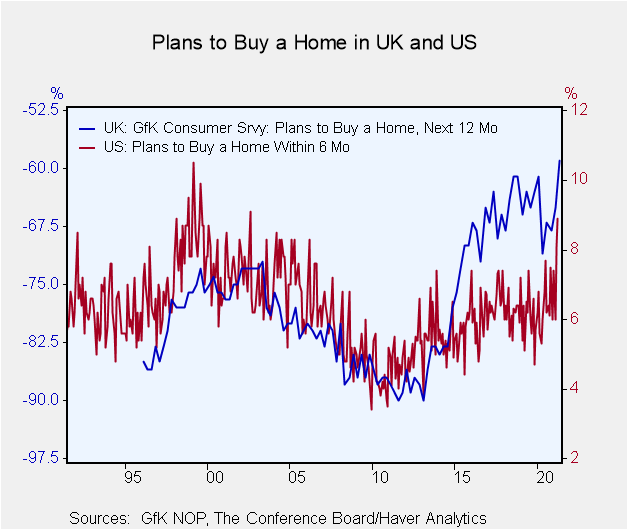

Still, it is arguably somewhat premature to expect this aggregate pattern to reverse itself anytime soon not least of course if a further package of US fiscal measures is on its way. It’s noteworthy on this score that consumers – and not just in the US – seem increasingly minded to carry on spending on big ticket items in the period ahead (see figure 7 below). Details of both the US and UK consumer confidence surveys, for example, reveal multi-year highs on plans to buy or build a new home. Ripple effects from this housing activity both for broader economic activity as well as for financial market activity could be of some further significance.

Figure 7: US and UK consumer confidence surveys – plans to buy a home

The ripple effect though that probably remains most critical to how financial market evolve in coming months concerns of course the broader impact from this on consumer price inflation. That will, in turn, hinge on a number of other issues including the global evolution of the pandemic, how much spare capacity is absorbed and on monetary policy responses. We will have more to say about this in the weeks ahead. For now though it seems clear that upside inflation risks are rising and that monetary policy settings seem extraordinarily loose for a world economy that’s in very firm recovery territory and where US fiscal policy is also already offering ample support.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.