Global| Dec 18 2020

Global| Dec 18 2020Good Riddance 2020!

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

It's that time of the year when economic forecasters typically publish reams of documentation containing their expectations for the year ahead. And it is fairly safe to assume that all of these forecasters are anticipating a much more [...]

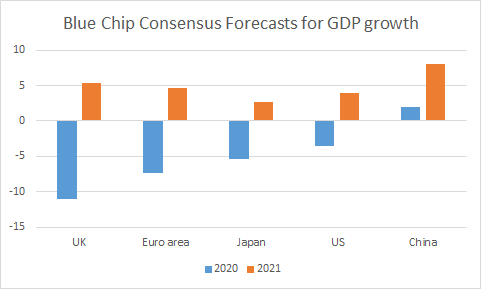

It's that time of the year when economic forecasters typically publish reams of documentation containing their expectations for the year ahead. And it is fairly safe to assume that all of these forecasters are anticipating a much more buoyant performance from the world economy in 2021 compared with the sorry saga that was 2020. In fact the latest consensus forecasts from the monthly Blue Chip survey of economic forecasters suggest that deep contractions in output this year should give way to a strong rebound in GDP growth in 2021 (see figure 1 below). Among major developed economies, the UK and Euro area are expected to see a relatively robust recovery in growth though the US and Japan should not be that far behind. But with GDP growth projected to be 8%, China is expected be one of the strongest performers next year (and certainly relative to major developed countries) and even though it will almost certainly not see any drop in output this year and thus outperformed other major economies as well. This can largely be chalked up to firmer underlying growth potential, an earlier recovery from the COVID pandemic as well as solid policy support.

Figure 1: Blue Chip Consensus Forecasts for GDP growth in 2020 and 2021

Source: Wolters Kluwer/Haver Analytics

It is not our intention here in this brief commentary to wade through all the finer details that underpin those aforementioned forecasts. Instead we lay out below a few of the likely key global drivers. We look too at some of the key issues that policymakers are likely to grapple with as the world economy finds some renewed poise.

Our key points are as follows:

• Further vaccine relief alongside milder temperatures in the northern hemisphere ought to help generate a synchronized revival in global growth from around Q2 2021. Ebbing uncertainty will be a key driver of this revival via the likely venting of pent-up demand.

• High levels of uncertainty pervade many sectors and many countries. While there is – at present – still a great deal of uncertainty about the COVID-19 virus, the world economy has also been restrained in recent years by elevated uncertainty about international trade. On both counts – COVID and trade – there are good grounds for anticipating that uncertainty will ebb.

• Additional global factors that ought to offer support to economic growth in the period ahead include loose financial market conditions, renewed economic vigour in China (as already discussed above) and inventory restocking. Low inflation and a likely still-high degree of fiscal and monetary policy accommodation will also be key.

• The key policy challenge that had been dominating macroeconomic debates prior to the virus is likely to dominate again as a revival in global growth matures. How can we generate firmer growth and higher inflation in a world of near-zero (or negative) equilibrium real interest rates and lacklustre productivity growth? The merits of activist fiscal policy over monetary policy and how to harness new technologies in order to boost underlying productivity growth will probably feature more strongly in that debate.

In what follows we examine some of the latest trends in some key data points that reinforce some of these key messages.

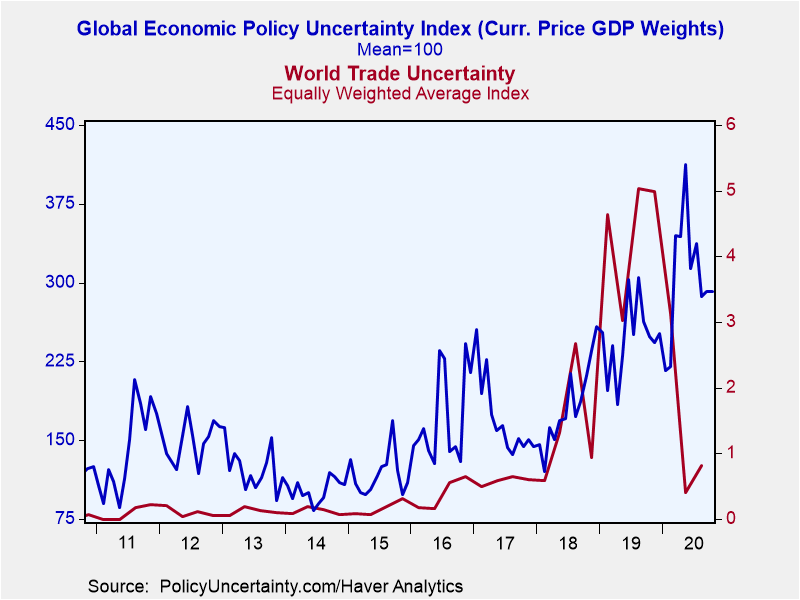

We look first at uncertainty. Measuring uncertainty is of course fraught with great difficulty. But there are now several indices that are compiled by researchers (at www.policyuncertainty.com) that aim to capture this elusive concept by tracking mentions of the word ‘uncertainty' in relation to other factors (e.. policy, trade, the COVID pandemic). As measured these indices suggest at the global level that uncertainty about global trade issues has fallen dramatically over the past 12 months. Equally, global economic policy uncertainty, while still relatively high, has declined quite sharply in recent months as well (see figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Global economic policy uncertainty and trade uncertainty

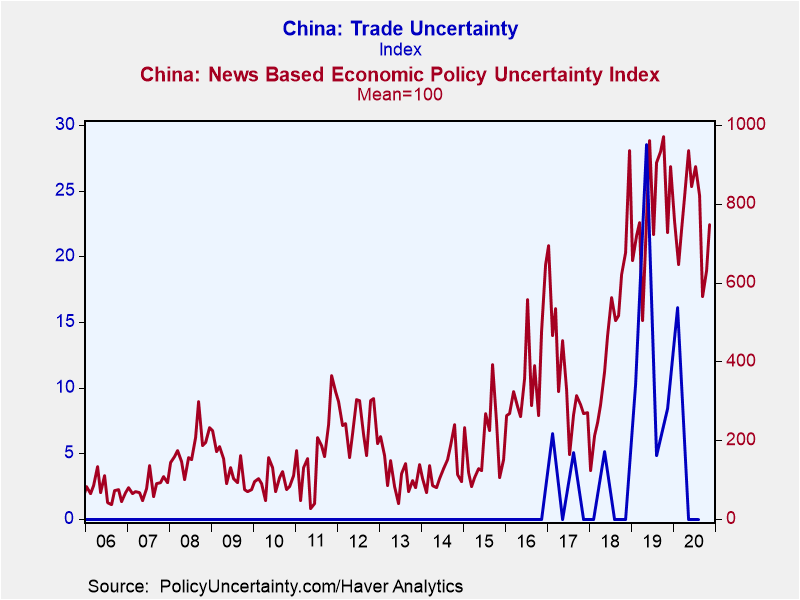

One of the country-specific drivers of these global trends is China. Trade uncertainty concerning China as well as uncertainty about the evolution of economic policy have both declined in recent months (see figure 3 below). On the trade side it is possible moreover that US-China trade tensions ease under the new US Biden administration which could elicit a further decline in uncertainty in the period ahead. Current low levels of Chinese inflation, an elevated current account surplus and some success (relative to other major economies) in dealing with the COVID crisis also leave greater scope for policy to deal with economic and financial instability in the coming months as well.

Figure 3: China's trade and policy uncertainty

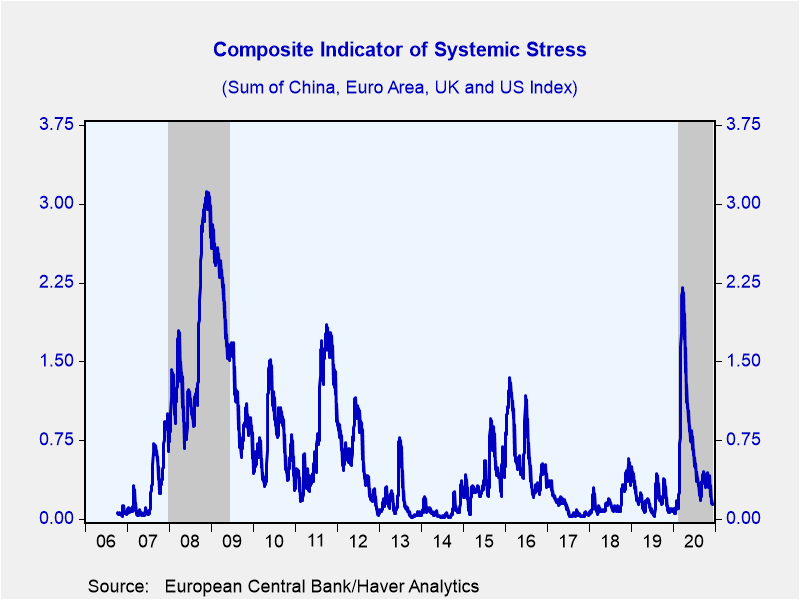

As for financial market stress, recent trends in the ECB's composite indicators also give cause for optimism (see figure 4 below). These indicators capture the underlying stress (or risk premium) that is priced into a whole range of financial market segments. They are aggregated in figure 4 below from the data for the US, Euro area, UK and China. That figure suggests that financial stress has declined markedly from a peak in late March. But it's only since encouraging news on vaccines has been reported over the past few weeks that these indices have returned to what might be construed as normal levels. This fits though with the idea that just as uncertainty about trade and economic policy has declined in tandem with encouraging news about vaccines so too has financial market uncertainty. And that bodes well for domestic demand growth in the year ahead.

Figure 4: Financial market stress indicators have fallen back to normal levels

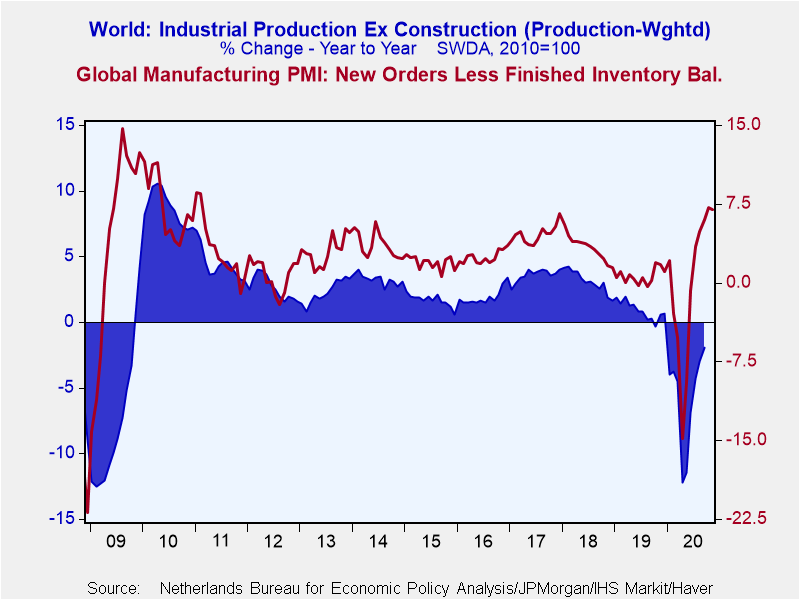

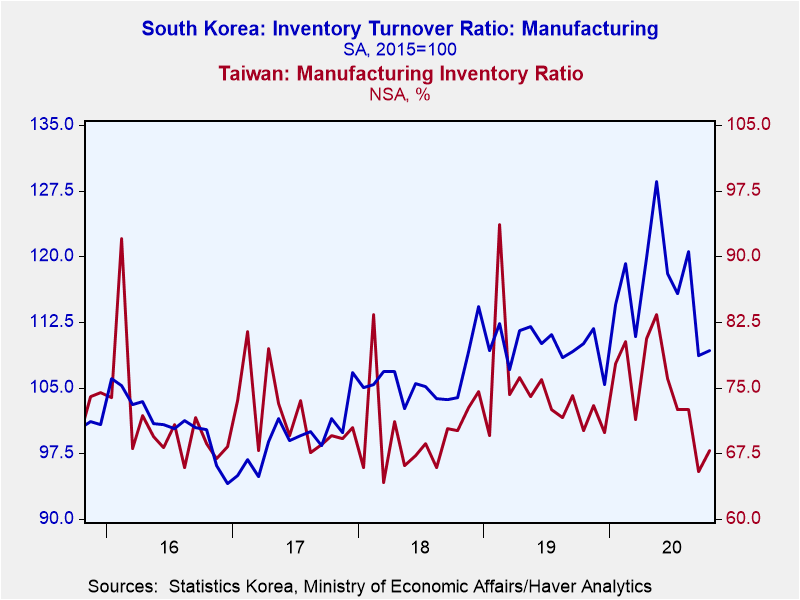

As for inventories, the latest raft of purchasing managers surveys show that stocks of finished inventory are falling at the same time as new orders for manufactured goods are rising. This has meant that the average spread between balances on new orders and inventory – typically a very good leading indicator of the global economic cycle – has climbed very close to decade highs (see figure 5 below). Furthermore inventory to shipment ratios (also known as inventory turnover ratios) have fallen to low levels in some of the Asian countries that are key bellwethers of the global trade and tech cycle (e.g. in South Korea and Taiwan, see figure 6). These developments bode well for the likely cyclical evolution of global industrial production and global trade in the coming months.

Figure 5: New orders to inventory spread in Global PMI survey close to decade highs

Figure 6: Inventory to shipment ratios in Korea and Taiwan

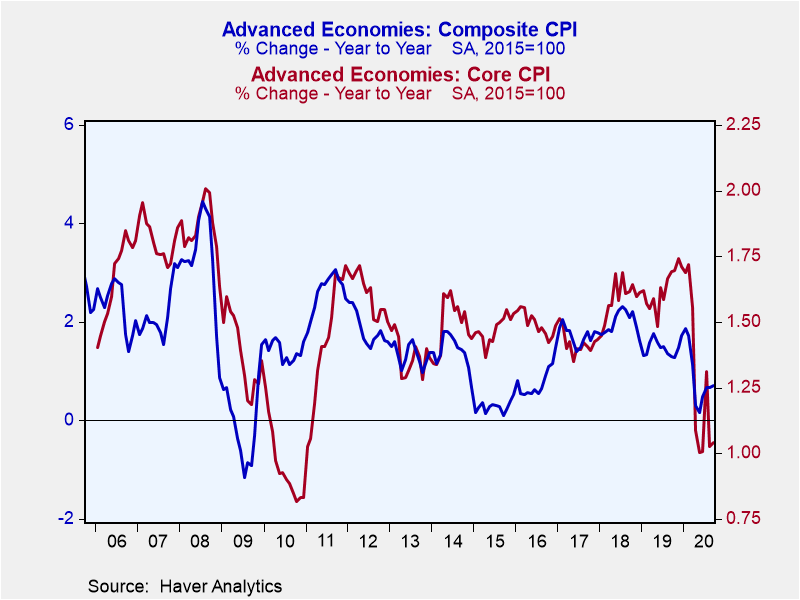

Our next positive support valve for global growth concerns low inflation levels and the degree to which this should help maintain accommodative monetary (and fiscal) policy. Haver's aggregations of consumer price inflation in the advanced economies (see figure 7) illustrate a well-known feature of the global macro environment in recent years namely that headline and underlying (core) inflation levels have on the whole been below the 2% levels that typically earmark Central Bank's inflation targets. And that's notwithstanding extraordinary degrees of monetary accommodation from the world's major Central Banks. What's more, both headline and core inflation levels are at present well below these target levels despite the provision of even more monetary accommodation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks to the pandemic and the large pockets of excess capacity that have opened up in various sectors, it seems highly likely moreover that inflation levels will remain quiescent in the coming months.

Figure 7: Headline and core CPI inflation in advanced economies

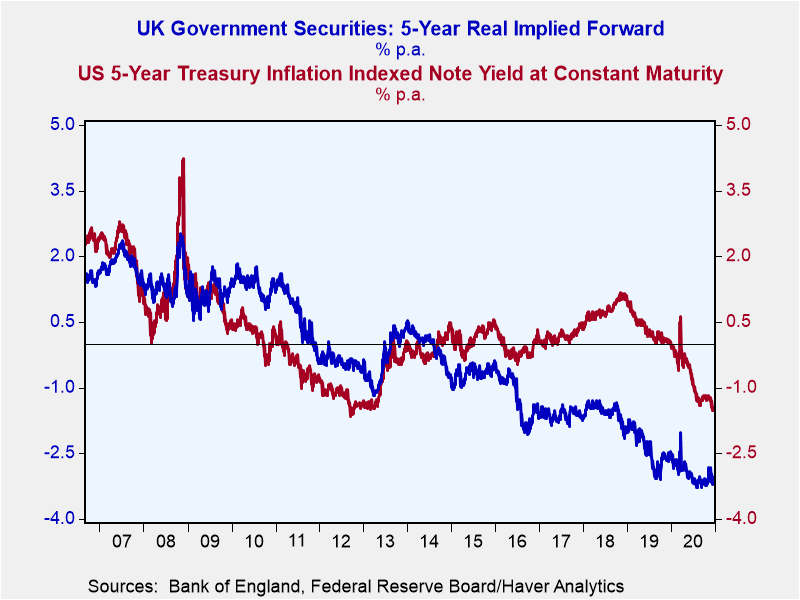

This brings us to the final issue that will clearly be of some importance in looking ahead to 2021 which will be how much monetary and fiscal policy accommodation can policymakers afford to leave in place as the world economy regains some poise. The answer to this, at least in the monetary policy nexus, concerns the trajectory of inflation (and growth). For fiscal policy the broad trajectory of real interest rates will matter as well. Understanding why real interest rates are as low as they are (see figure 8 below) and whether or not they will rise in coming months will certainly be a critical talking point at upcoming Central Bank meetings. The appropriate monetary and fiscal policy mix and how to harness higher productivity growth will surely form part of that discussion among other policymakers too.

Figure 8: Real market-determined real interest rates in the US and UK

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.