Global| Mar 01 2021

Global| Mar 01 2021Pioneer of the Inflation Targeting Adds Asset Prices to Its Framework, While The Fed Adds More Fuel

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

Starting March 1, The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RNZ) will consider the impact on housing prices when it debates monetary policy decisions. In doing so, RNZ becomes the first central bank to acknowledge that monetary policy [...]

Starting March 1, The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RNZ) will consider the impact on housing prices when it debates monetary policy decisions. In doing so, RNZ becomes the first central bank to acknowledge that monetary policy decisions could influence asset prices at times adversely---lifting valuations far beyond fundamentals.

RNZ argues that the inclusion of house price sustainability fits in with their financial stability mandate. RNZ would be using prudential tools – like loan-to-value ratios, bank stress testing, and capital requirements against particular types of mortgage lending---when it decides whether monetary policy action is needed to "ensure house price sustainability."

News that RNZ now includes asset prices in its policy deliberations has been ignored or overlooked by most. Critics may say it's a small country, and their approach to monetary policy should have no carryover or import to what others do.

But that would be wrong. RNZ pioneered the inflation-targeting framework, introducing this policy regime in 1990; since then, it has been adopted by central banks worldwide.

One would think that the central bank that created and has been using the inflation-targeting framework the longest would know a lot about the pros and cons of this approach more than anyone else. RNZ has learned, as have other central banks, that a simple inflation-targeting rule to conduct monetary policy is not easy or without unintended consequences.

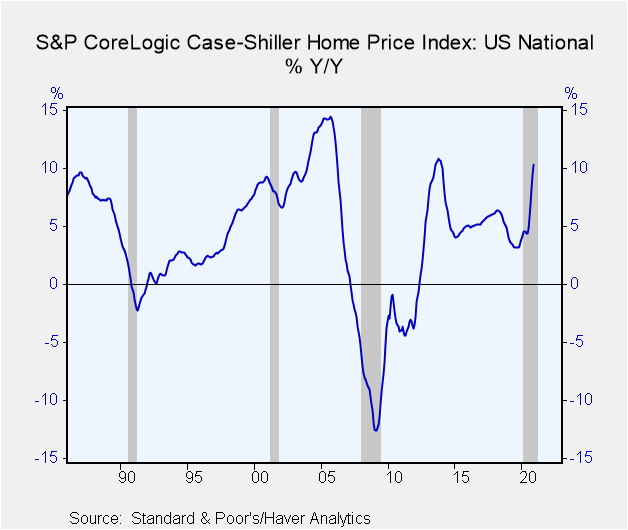

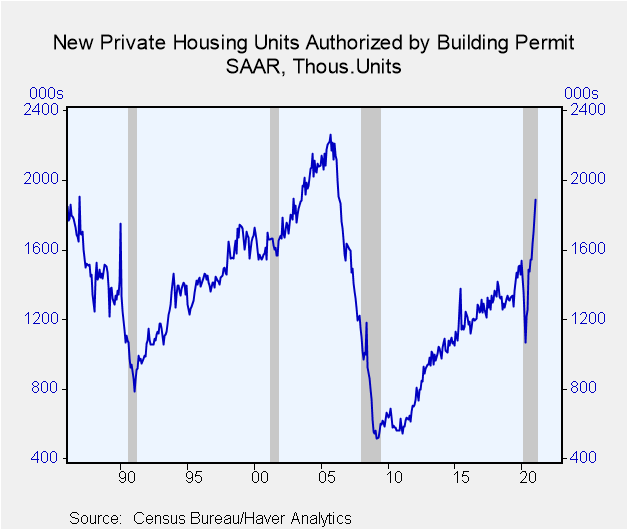

Boom-bust credit and asset cycles have been two of the unforeseen side effects of inflation targeting. In the US, boom-bust asset cycles, linked directly to easy money policy and the promise to maintain it for an extended period, triggered the last two recessions.

Central banks have for decades struggled with how to incorporate financial stability issues (i.e., unhinged gains in asset prices) within the structure of the inflation-targeting framework. The decision by RNZ puts financial stability as a co-equal to that of price stability. It would be wise for other central banks, including the Federal Reserve, to consider the actions by the RNZ.

Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve does not appear to be on the same page. Unlike the RNZ who is now monitoring monetary policy influence on asset prices, the Fed adds fuel to the asset price boom.

When testifying before Congress last week, Mr. Powell stated, "The housing sector has more than fully recovered from the downturn." That is an understatement. The housing sector is booming, evident with record-high prices, following double-digit gains in 2020, and sales of new and existing homes and permits to build new ones at the highest levels since the housing bubble mid-2000s.

But even after acknowledging the robust housing sector, Powell said the Fed would continue with mortgage-back securities purchases providing more monetary fuel to a red-hot sector.

Senator Pat Toomey, the Republican senator from Pennsylvania, suggested to Mr. Powell that the Fed's easy money policy contributes to "bubbles," citing rapid increases in real estate, commodities, and other assets. Mr. Powell admitted, "There is certainly a link," but cited other factors as well.

With asset prices at record levels, the RNZ and the Fed employ diametrically opposite policies to ensure price and financial stability. Who is right? My money is on the tiny central bank on the other side of the world.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.