Global| Mar 19 2021

Global| Mar 19 2021The Fed's Dot Game: "Something Missing"

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

The Federal Reserve members' updated projections at the March 16-17 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) paint an optimistic economic view and an unrealistic monetary policy picture. Policymakers now agree with private forecasters [...]

The Federal Reserve members' updated projections at the March 16-17 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) paint an optimistic economic view and an unrealistic monetary policy picture. Policymakers now agree with private forecasters that the US economy will experience in 2021 its faster growth rate (+6.5%) since the early 1980s. And relatively strong growth will continue for an additional two years, enabling policymakers to hit their mandate of full employment by 2022 (3.9% jobless rate) and price stability (2%) as well. Yet, policymakers plan to keep official rates near zero into 2024.

How realistic is that? It's not. Policymakers will soon have a credibility problem, if not already, as the economy and markets force a policy adjustment long before 2024.

The Dot Game!

The Federal Reserve started to provide economic and policy projections in 2012. The projections summary comprises the members' estimates of growth, unemployment, and inflation, and it also shows a "dot" plot of each member's view of official policy rates. The summary is not an official Fed economic forecast, nor is it intended to be used as a script to alert the market for the timing of potential changes in policy rates. But the financial markets view it as one.

At the press conference following the Federal Open Market Committee meeting of March 16-17, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell stated that actual economic outcomes would dictate policy decisions and not forecasts.

Nonetheless, it would be interesting to see how Mr. Powell would have responded to a reporter asking, "If the economic projections are close to the actual outcomes, is it realistic to think that policy rates remain at zero until 2024"?

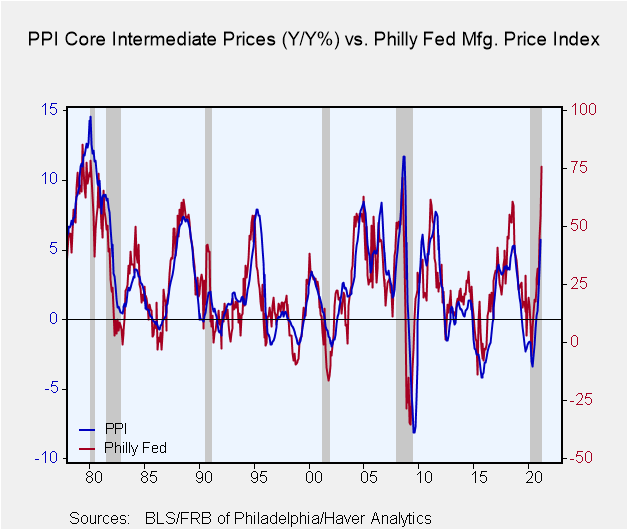

How long the Fed can continue to push this dovish policy view is difficult to pinpoint, but economic conditions are quickly changing for the better. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia composite index of manufacturing jumped nearly 30 percentage points to 52% in March, the highest reading since 1973. The price index, which has a remarkably high correlation with the producer prices core intermediate price index, jumped 20 points to 75%, highest reading since 1979.

How long the Fed can continue to push this dovish policy view is difficult to pinpoint, but economic conditions are quickly changing for the better. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia composite index of manufacturing jumped nearly 30 percentage points to 52% in March, the highest reading since 1973. The price index, which has a remarkably high correlation with the producer prices core intermediate price index, jumped 20 points to 75%, highest reading since 1979.

Recovery in the manufacturing sector is always a harbinger of faster economic growth. But pent-up demand in the current cycle is centered more so in the service sector. So if the manufacturing industry is expanding at a rapid rate at the same time, the odds of solid growth performance and rise in inflation increases doubly so.

A dovish monetary policy was necessary to help cushion the economy from the fallout from the pandemic. A dovish rate stance is the wrong policy approach when the economy runs full speed as it will foster imbalances that threaten economic stability. The jump in long-bond yields following the FOMC meeting indicates financial market participants believe there is "something missing" in the "dot" plot on policy rates.

A dovish policy stance (i.e., zero rates for the next three years) is not a friendly finance policy when inflation pressures are building. Expect long-bond yields to rise to 2% soon, and then 3% by year-end.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.