Global| Nov 24 2020

Global| Nov 24 2020The Light at the End of the Tunnel

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

"Light at the end of the tunnel" is a phrase that will likely be deployed very frequently in the coming weeks. That's because of the news concerning several vaccines for COVID-19 which have clearly generated heightened hope that the [...]

"Light at the end of the tunnel" is a phrase that will likely be deployed very frequently in the coming weeks. That's because of the news concerning several vaccines for COVID-19 which have clearly generated heightened hope that the crisis could soon be over. But how bright is that light, how long is the tunnel and how much time will it take to reach the end?

Our focus with these metaphorical questions is obviously on macroeconomic matters. And - staying with the metaphoric - our answers below assess some of the obstacles that need to be navigated as we approach the end of the tunnel and that could still brake progress as we emerge into the light. Some of those obstacles involve the near-term challenges that concern second waves and/or still-high virus incidence levels in some economies. And some of them concern more structurally-rooted barriers including a) debt sustainability issues; b) higher levels of long-term unemployment; and c) a likely further shift to de-globalize the world economy. Those structural barriers may well restrain progress toward normality when those near-term challenges have been overcome. At the very least though they argue for a very slow withdrawal of policy stimulus in the period ahead as well as intensified international policy co-ordination.

Near-term hurdles

Let's start with some of the near-term hurdles that could still derail the world economy's path to normality in the coming weeks. To be clear we will not address vaccine efficacy, the logistics of roll-out programmes and how long herd immunity might take to achieve, as important as those issues are. Our focus instead concerns current incidence levels and how these are inhibiting efforts to ease lockdown restrictions, reduce social distancing and more generally bring economic activity onto a more normal setting.

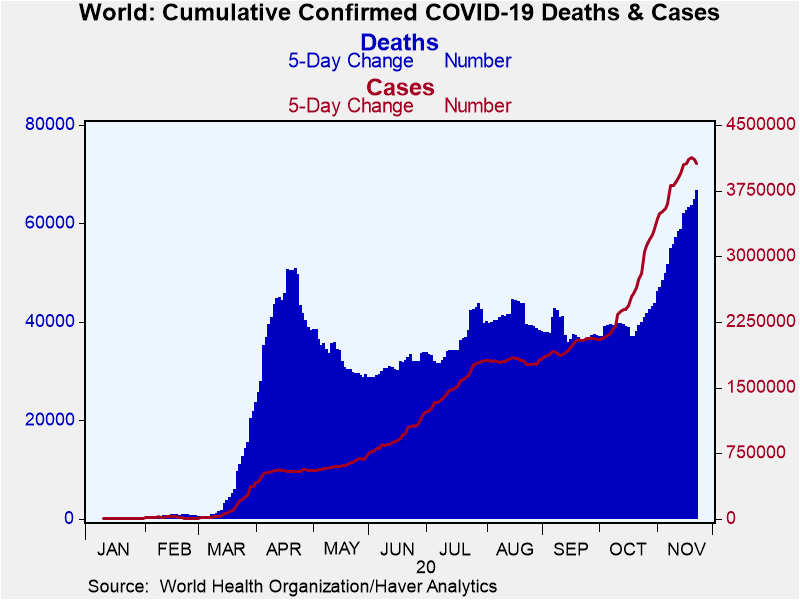

On current incidence levels the latest data reveals bad news and good news. The bad news is that global case numbers have continued to climb sharply in recent weeks as evidenced in figure 1 below. The daily global mortality rate has also continued to rise and has increased more than 80% since mid-October.

Figure 1: Global COVID case numbers and deaths

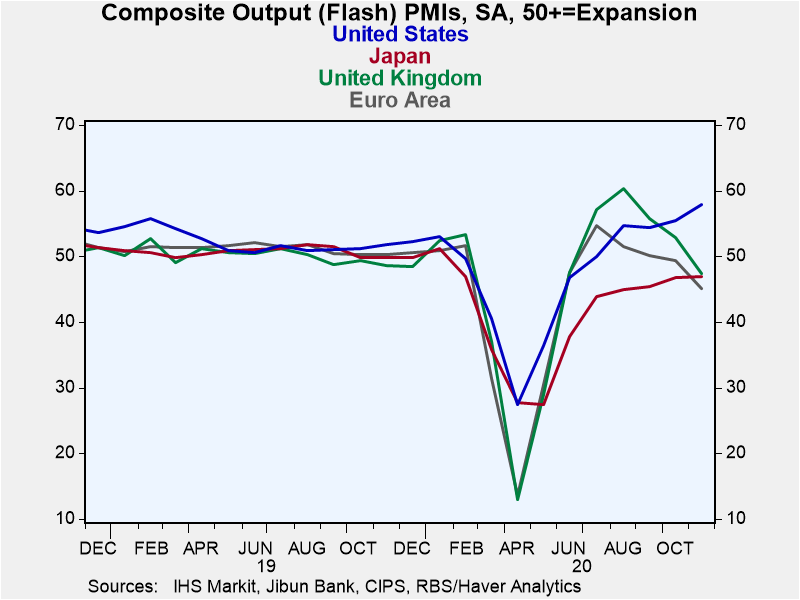

The latest data this week also suggest heightened economic damage from recent efforts to stifle the virus. Flash composite Purchasing Managers surveys for November, for example, fell sharply in the UK and Euro area. And notwithstanding a better-than-expected reading from the US, most of these surveys, including Japan's, have either moved into - or have remained in - contraction territory (see figure 2 below). Many forecasters had already slashed their forecasts and are anticipating negative outcomes for GDP growth in these economies in Q4. But if these PMI survey results find an echo in other data points, there may well be some further downward revisions in the days ahead.

Figure 2: Flash PMI survey results suggest negative Q4 GDP prints in Europe and Japan

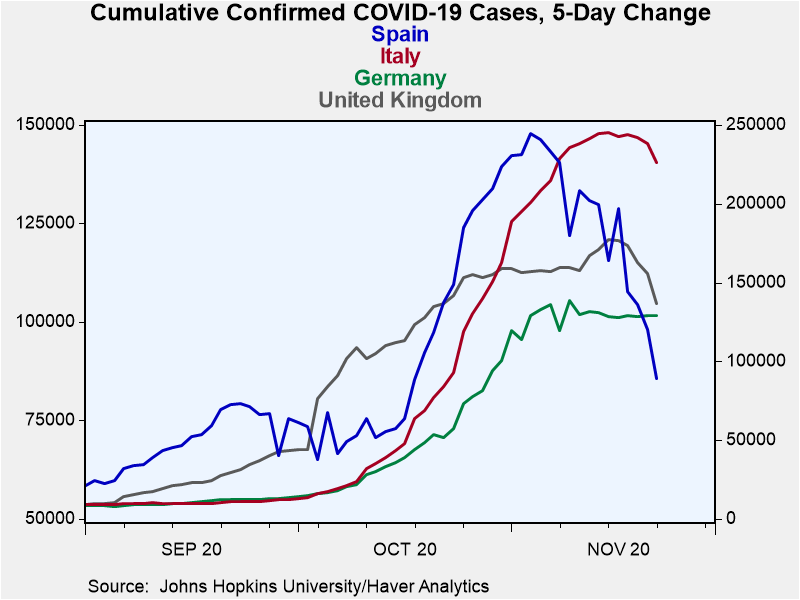

The good news though is that many European countries are now showing signs that they have turned a corner on new COVID cases. Over the past two weeks a number of countries have reported a decreasing daily incidence level after implementing more restrictive mitigation measures. In Europe as a whole the overall biweekly change across the continent is still extremely elevated but it is trending steadily downwards (see figure 3 below).

Figure 3: COVID case numbers in selected European countries

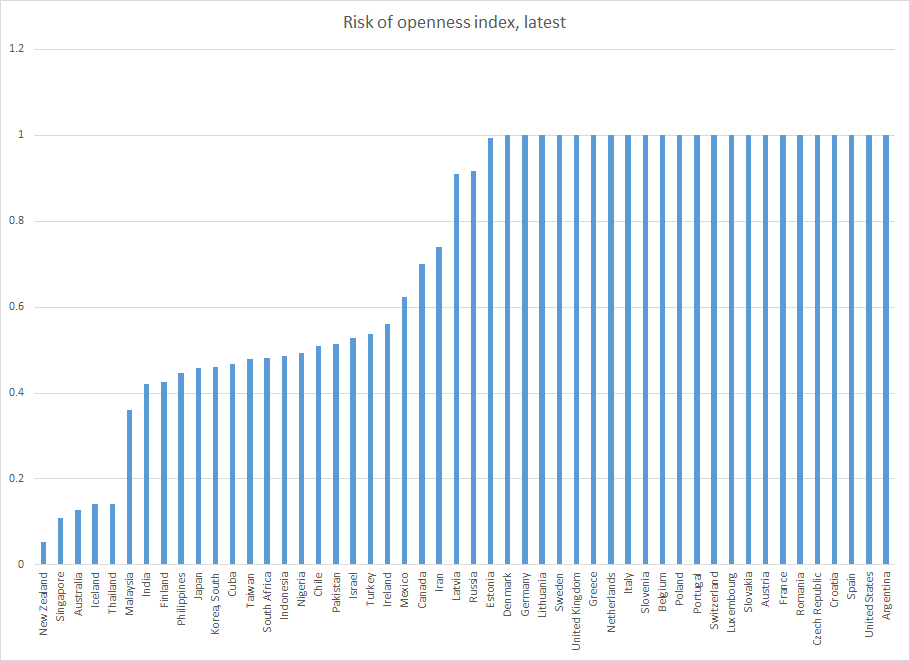

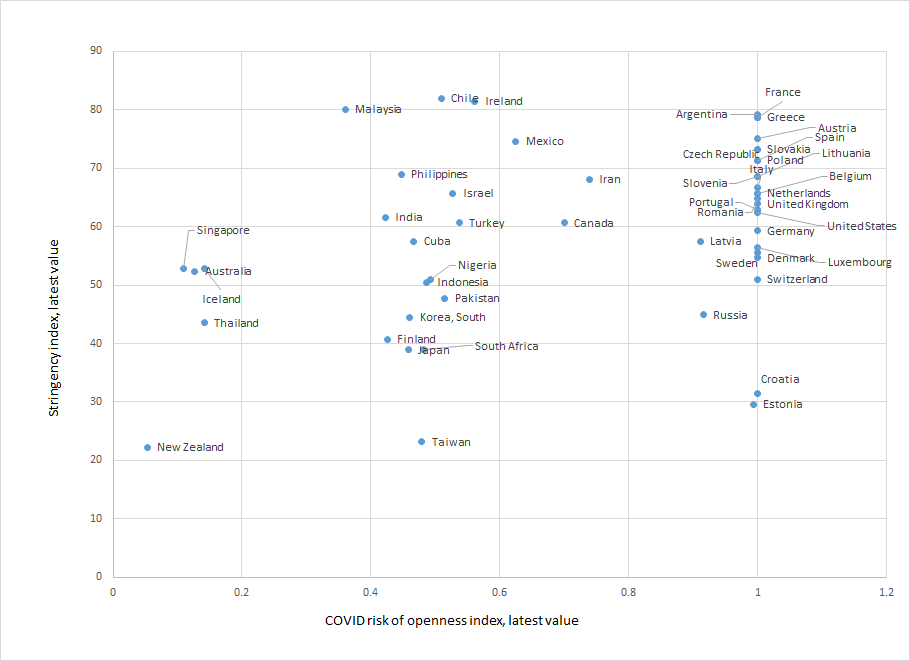

It's still obviously far too soon to sound the all clear however. Oxford University's Risk of Openness Index still shows that many countries remain at very high risk of further infection absent offsetting policy initiatives as evidenced by the relatively high number of countries that appear on the right hand side of figure 4 below.

Figure 4: COVID risks of openness index for a selection of developed and developing countries

Source: Oxford University, Haver Analytics

Measured moreover with reference to Oxford's Policy Stringency index it's possible that some countries may have to instigate further measures that restrict mobility in the coming weeks in order to fend off the virus (and before a vaccine arrives in force). In figure 5 below we've charted the latest data for the Oxford Risk of Openness index versus the Oxford Policy Stringency index. Countries that appear in the northwestern area of the chart have low COVID risks and highly stringent regimes to deal with those risks. Conversely countries that appear in the southeastern area of the chart have high COVID risks but relatively relaxed lockdown regimes. This admittedly simplistic analysis suggests that several Asian countries as well as Australia are more likely to ease lockdown stringency in the period ahead. Several Eastern European countries such as Croatia, Estonia and most notably Russia together perhaps with Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland may need to see tighter restrictions.

Figure 5: COVID risks of openness versus policy stringency

Source: Oxford University, Haver Analytics

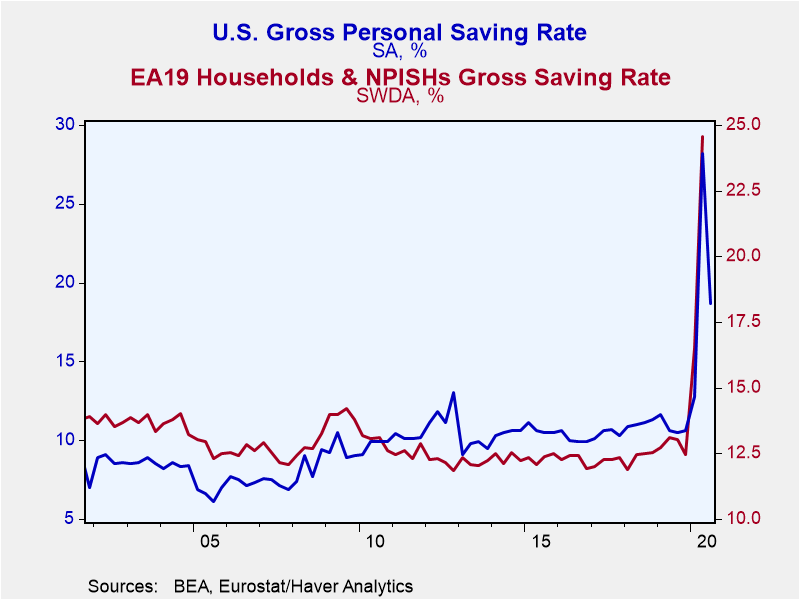

Still, notwithstanding these near-term concerns, recent vaccine developments undeniably bode well for a significant easing of restrictions on economic activity in 2021. Many developed countries ought to be able to implement speedy vaccination programmes for the most vulnerable members of their society in the coming months. Indeed some policymakers are even suggesting – largely because of this - that ‘normality' may have resumed by next April. From an economic standpoint that would mean those sectors that have been severely hampered by impaired mobility, such as hospitality and travel, will be much more viable. It will mean more generally that a great deal of pent-up demand can be vented into those sectors (as well as others) as uncertainty unwinds. It's worth noting on that last score that household saving rates in the US and Euro area stood at 19% (in Q3) and 25% (in Q2) respectively. So, there are ample resources to fund satisfying pent-up demand.

Figure 6: US and Euro area household savings rates

Longer-term obstacles

This, in turn, means that although the risks to Q4 2020 GDP forecasts (and possibly Q1 2021) are still probably tilted to the downside, the outlook for growth in 2021 is much more promising. Indeed forecasts for the year as a whole are more likely to be revised up than down. The great challenge though in gauging the degree of upside risk concerns the trade-off between policy accommodation, cyclical positives from vaccine (and broader virus) relief and some of the structural obstacles to trouble-free economic growth that we alluded to above. Those obstacles concern extraordinarily high levels of debt (often in both the private and public sector domain) and how to generate high levels of both wage income and export income to adequately service those debts.

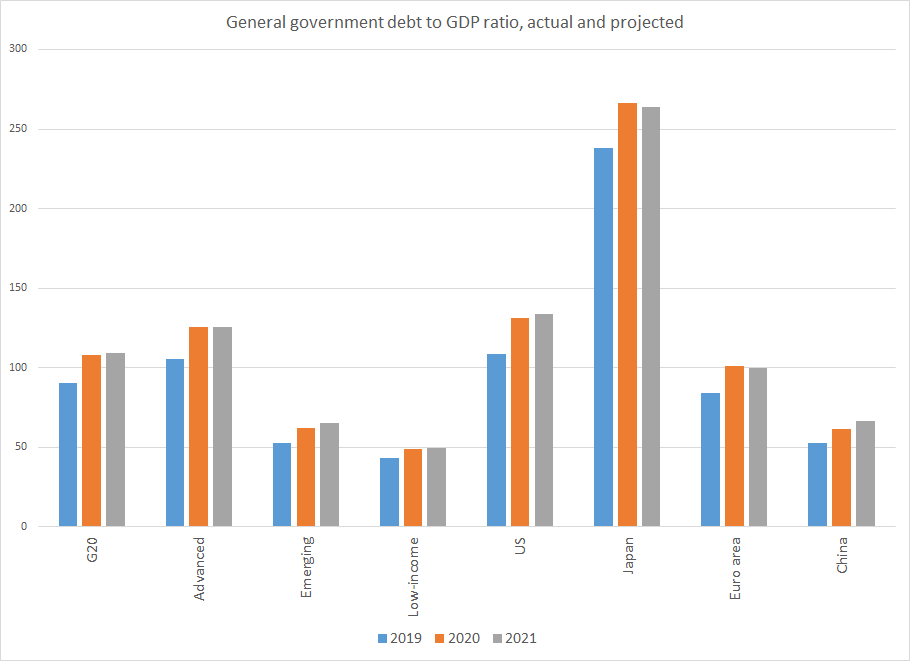

Firstly on the debt side we note the COVID pandemic has pushed aggregate levels in the government sector to new highs. Compared to end-2019, average 2021 debt ratios are projected by the IMF to rise by 20 percent of GDP in advanced economies, more than 10 percent of GDP in emerging market economies, and by about 7 percent in low-income-countries (see figure 7 below). These increases come on top of debt levels that were already historically high. While many advanced economies still have the capacity to borrow, emerging markets and low-income countries face much tighter limits on their ability to carry additional debt.

Figure 7: General government debt to GDP ratios, actual and projected

Source: IMF, Haver Analytics

As for labour incomes COVID restrictions – shutting down major sectors of the economy – have already generated large numbers of workers (20-30% of the workforce in many countries) that have been unable to work. In the US, this has mostly manifested itself in unemployment; in most European countries, ‘furlough' schemes have generated more of a reduction in hours worked. As economic recovery takes hold much of this displacement ought to unwind. But there is still much scope for so-called scarring effects from a loss of skills and a loss of education in the existing workforce. These factors along with reduced mental wellbeing could reduce future employment and wage income.

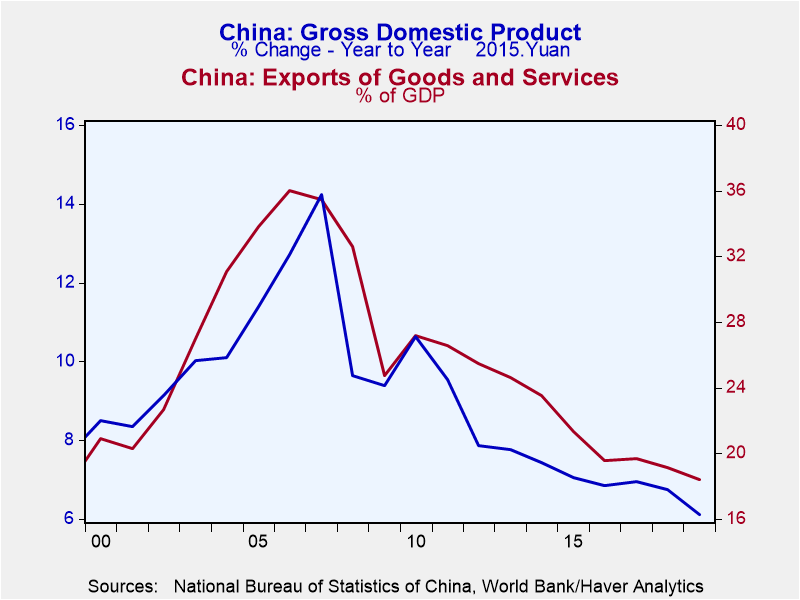

Finally on export incomes the concern here is de-globalization. Many observers believe the COVID pandemic could act as an even bigger accelerator towards increased protectionism and a renewed on-shoring of manufacturing capacity because the virus has exposed the vulnerabilities of relying too much on long supply chains. All of this is obviously already unfolding in an environment of reduced international cooperation. For countries – and many emerging countries in particular – that have been highly dependent on export incomes both as a source of growth and to service existing debts, this is clearly a problem. It's certainly no coincidence that China's reduced reliance on exports (and investment) in recent years and heightened dependence on domestic consumption has coincided with much weaker overall economic activity as evidenced in figure 8 below.

Figure 8: China's reduced reliance on exports

The implication of this is that while optimism toward 2021 is undeniably warranted we should not get too carried away. Debt sustainability issues, labour market scarring and a further push to de-globalise the world economy are likely to be lasting legacies of the virus. And policymakers will need to be mindful of their potential consequences for financial stability and political stability. Premature withdrawal of monetary and fiscal policy stimulus may certainly be difficult as would an absence of international policy co-ordination. There is still light at the end of the tunnel and many countries are likely to reach that end in the coming months. Their speed of progress beyond the tunnel however is still open to some questions.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.