Global| Oct 21 2019

Global| Oct 21 2019The State of the Consumer: Views From Retail & Banks

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

How strong is the consumer sector? It depends on where you sit in the food chain of consumer sales and finance. Nominal growth of consumer spending in 2019 has slowed to its weakest growth rate in three years, with many traditional [...]

How strong is the consumer sector? It depends on where you sit in the food chain of consumer sales and finance.

How strong is the consumer sector? It depends on where you sit in the food chain of consumer sales and finance.

Nominal growth of consumer spending in 2019 has slowed to its weakest growth rate in three years, with many traditional retailers seeing no growth in top-line sales. And yet large commercial banks indicate that their consumer finance arm shows a "healthy consumer".

The difference in the direction and tone of business is very straightforward; retail is counting how much consumers are spending at their establishments, while commercial banks are counting how much consumers are paying in interest when they borrow to spend.

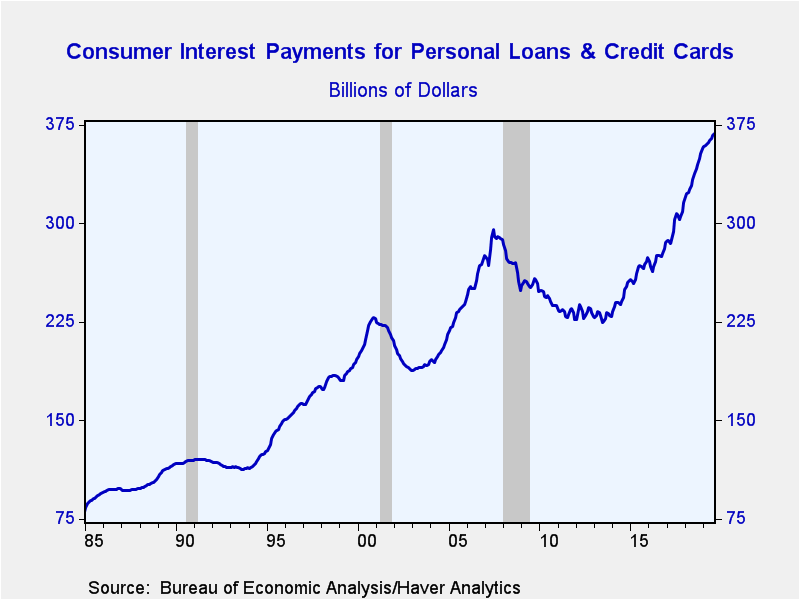

Banks are happy (for now) as consumer interest payments at record levels are rising more than twice as fast as consumer spending. Yet, that trend can’t continue for long as rising interest expense drains consumer liquidity, weakens the consumer ability to spend, dampens growth and eventually ends up impacting retail and banks alike.

Through the first 9 months of 2019, nominal consumer spending—which includes all goods and services and traditional and ecommerce retailers--- is running less than 4%, a drop-off of roughly 125 basis points from the 2018 performance.

Although nominal income growth is running close to 5%, consumers still saw the need to increase consumer borrowing (i.e., personal loans and credit cards) by 5% in order to support spending. Perhaps that reflects the unevenness of income growth and lack of a liquidity buffer among various income groups.

On the surface, the growth of consumer borrowing is not excessive, but what is excessive is how much it costs consumers to borrow.

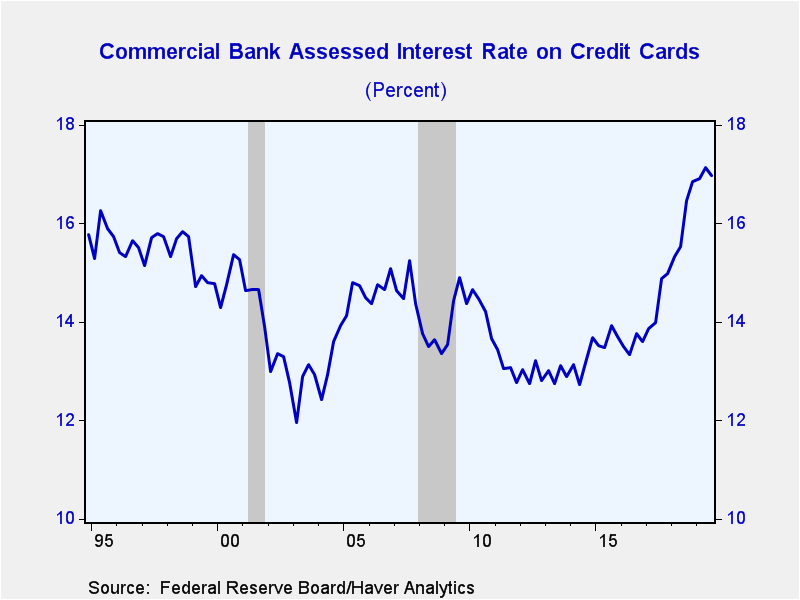

Personal loan rates at commercial banks stand at 10%, and average credit card rates stand at 15%. However, the actual cost of credit card borrowing is much higher, since banks charge interest not only on the daily balance but also on prior months interest rate charges, along with other fees.

The Federal Reserve has estimated the true cost of credit card borrowing. The assessed interest rate charges on all credit card accounts averaged 17% in 2019 (200 basis points above published average rates), and represent the highest assessed rate since the Federal Reserve started measuring the all-in-costs of credit card borrowing in 1995.

Record high rates for credit card borrowers runs counter to the JP Morgan view that "consumer remains healthy, with growth in wages and spending, combined with strong balance sheets". A "good" consumer borrower, with "good" wage growth and "good" balance sheets should not be paying record high interest rates.

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, consumer interest rate payments hit a new record high of $368 billion in Q3 2019, more than one third above the peak of the 2008 financial crisis, and 10% above what consumers paid in 2018.

In short, rising interest expenses are sucking the "spending power" out of the consumer. Retail is already seeing the impact and banks will soon see it as well.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.