Global| Apr 30 2021

Global| Apr 30 2021To Sustain the Economic Cycle, The Fed Must Shift The Focus To Financial Outcomes

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

One year ago, the economic outcomes of record lob loss and business closings were the primary focus of the monetary policy. The Fed took the unprecedented actions of cutting official rates to record lows, buying billions of debt [...]

One year ago, the economic outcomes of record lob loss and business closings were the primary focus of the monetary policy. The Fed took the unprecedented actions of cutting official rates to record lows, buying billions of debt securities, and direct lending to small companies. One year later, to sustain the economic recovery the Fed has help engineer, monetary policy needs to shift the focus to financial outcomes.

Fed policy relies heavily on expectations to achieve its intended results. Policymakers believe that they must maintain a declared policy long enough to influence people and investor expectations to produce the desired results. But the risk to this policy approach is that expectations become unhinged so much that expectations can become a destabilizing force at some point.

Promises and expectations of easy money for an extended period have helped pushed asset values to extreme levels, matching or exceeding some valuation measures of the bubble periods. If not at a tipping point, promises of easy money will trigger more risk and speculation, pushing prices even higher in the process.

Famed-investor Jeremy Grantham recently said the history of bubbles shows that the bigger the gain, the more significant the loss in the end. If that proves to true again, we are in for a world of hurt.

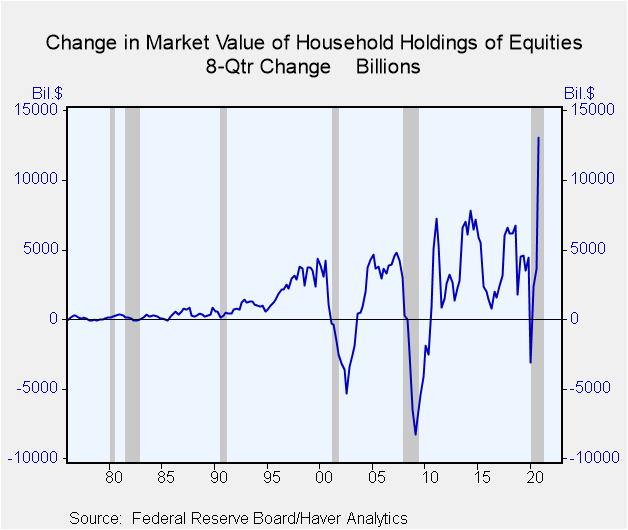

In the two years ending in Q4 2020, the market value of household equities increased $13 trillion, more than double the gain in any other period. The scale of the equity declines following the tech and housing bubbles exceeded the scale of the increases, so if history repeats, the scale of the next slide would be more than 2X times that of the Great Financial Recession.

In the two years ending in Q4 2020, the market value of household equities increased $13 trillion, more than double the gain in any other period. The scale of the equity declines following the tech and housing bubbles exceeded the scale of the increases, so if history repeats, the scale of the next slide would be more than 2X times that of the Great Financial Recession.

Another critical feature is the duration of the excessive asset price cycle. That's because the longer it is in place, the greater the chances the elevated asset prices have spread their wings and are being used to sponsor or finance other activities.

For example, companies paid their workers, enticed other people with stock options during the tech bubble, and used the value of the stock as collateral for investment purposes. So when tech equity prices fell hard, there was a direct hit to people's compensation and investment spending. During the housing bubble, people used their houses as a bank, financing additional borrowing and spending. The collapse in house prices triggered a sharp and abrupt drop in consumer spending and a margin call on homeowners who double-dipped.

The promise of easy money has triggered huge record gains in equities, houses, and new asset classes, such as cryptocurrencies. It will not be a surprise if these are directly and indirectly connected, with investors using winnings in one asset class as a source of liquidity or profits to take risks in another. Tesla used the profits from its investment in cryptocurrencies to make its Q1 operating profit look better on the surface. No one knows the linkage between the asset markets nowadays, nor did anyone know about the potential financial contagion during the housing market bubble.

Promising no rate increases until 2023 might have been an appropriate policy stance one year ago, but not now when the fiscal policy provides more direct spending support to the economy than ever before in the post-war period.

Even when the Fed does change course, it will start from an official rate of practically zero and move to a level of rates that will be low by historical standards. But a change would shock expectations, as no one expects a change to the easy money policy anytime soon.

It was curious to hear the Fed Chair, Mr. Jerome Powell, responds to questions about the equity and housing markets during the press conference following the Federal Open Market Committee meeting of April 27-28. Mr. Powell said there is "froth" in the equity markets and that policymakers are "watching" the housing market "vary carefully." In other words, the Fed is not taking away the punch bowl of easy money.

It is not a coincidence that the last two recessions resulted from asset price imbalances rather than too much general inflation. Policymakers do not manage economic and financial outcomes equally. The comments from Mr. Powell indicated that the same policy approach---focus on the economic signals and ignore asset market ones---is being used again.

Suppose policymakers do not shift the policy focus away from economic outcomes and financial results soon. In that case, the odds of Mr. Grantham being correct (again) will increase with every passing day.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.