Global| Sep 02 2020

Global| Sep 02 20202020 Drop In Operating Profits Mirrors 2008: Different Mix Shows The Need For More Fiscal Support

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

The sharp drop in operating profits in 2020 mirrors the decline of 2008. But the mix of profits is markedly different, with the bulk of the decline centered in non-financial industries. The crisis of 2020 is centered more so in the [...]

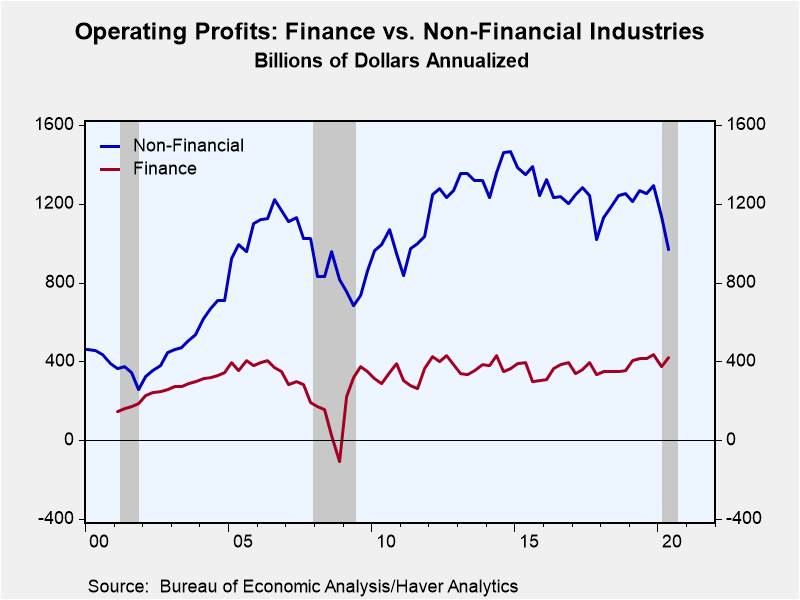

The sharp drop in operating profits in 2020 mirrors the decline of 2008. But the mix of profits is markedly different, with the bulk of the decline centered in non-financial industries.

The crisis of 2020 is centered more so in the general economy unlike the financial/banking crisis of 2008. That means the policy response requires more fiscal stimulus than monetary ease.

In Q2, the GDP measure of operating profits showed a decline of 11% and that comes on the heels of a 12% drop in Q1. The two-quarter decline of 23% nearly matches the 25% decline in operating profits in Q4 2008 during the Great Financial Recession.

But there are two key differences; first, the 2020 occurred over two quarters, while the decline in 2008 occurred in one; and second, the 2020 decline is almost entirely concentrated in non-financial companies while finance accounted for the bulk of the decline in 2008.

S&P 500 companies operating profits show a bigger decline, a different quarterly pattern, but a similar mix. According to the data compiled by S&P, operating profits for the largest companies declined 33% over the past two quarters. But the decline was concentrated in Q1, dropping 50% from the Q4 levels, while Q2 profits showed a gain of 36% over Q1.

The detailed industry profit data from S&P shows that the big turnaround from Q1 to Q2 is centered in finance. The financial sector lost money in Q1 but posted an increase in Q2. The GDP profit data also shows operating profits in finance rebounded sharply in Q2, rising 11%.

Trading gains and losses are considered part of S&P operating profits, but not in the GDP measure of operating profits. But the financial sector posted gains under both accounting frameworks. So trading gains are not the primary reason for the Q2 rebound in profits in finance.

The 25% decline in non-financial industries operating profits over the past two quarters is much more severe than the 15% drop in Q4 2008. Industry details from S&P show the weakest performers are energy, consumer discretionary, and industrials. Detailed non-financial industry data from GDP are not yet available.

The GDP data does show that the aggregate level of operating profits for non-financial companies stood at $966 billion in Q2. That's a decline of $330 billion from Q4 2019 and represents the lowest level of operating profits since 2011. Real profit margins for non-financial companies are estimated at 10.5%, the lowest level since 2009.

At mid-year 2020, non-financial firms employ nearly 10 million more workers compared to 2011. But that's after they have already shed more than 10 million workers since the start of the year.

Reports that previously laid-off workers are being told that they will not be rehired should not come as a surprise. Many firms don't have the level of profitability to support re-hiring. Lack of confidence in the future trends in business conditions also plays a role as the pandemic continues to disrupt businesses as does the on-and-off-again support from governmental policies.

Congress appropriated more than $3 trillion in fiscal stimulus, a record amount, to people and businesses. But that federal support abruptly ended on July 31st when Congress and the White House could not agree on a second round of stimulus. Failure to extend federal stimulus payments removes at least $750 billion a month from what people were seeing in terms of cash flow in Q2.

Equity investors have been betting that the combination of monetary ease and fiscal stimulus will build a strong and long bridge to keep the economy running until a vaccine is medically approved. With broad equity averages at record highs, the bulls have won the argument for now.

But what happens as the fiscal well runs dry, companies are operating with record debt levels and the monetary spigot is not pouring out liquidity, as fast as it was a few months back?

Cracks in the bull case are quickly starting to emerge. The consumer confidence index for August dropped 7 points to 84.8. That's a new low for 2020, reversing the federal stimulus-related gains of the prior three months.

People's assessment of labor markets turned sharply negative, consistent with the million-plus jobless claims being filed week after week. People are also expressed concern about their financial well-being at the same time the S&P 500 hit a new record high.

The equity market is not the economy, but the direction of the economy will ultimately determine if the equity market can maintain the lofty levels for the simple reason investors are banking on better news in corporate earnings. But without a new round of fiscal stimulus, it's hard to see how corporate earnings can meet bullish investor optimism.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.