Global| Nov 20 2018

Global| Nov 20 2018Asset Cycles & Financial Crises: "Made In Washington"

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

The Federal Reserve is facing the growing possibility of the third asset price bust in the last two decades. And each one has a "Made in Washington" label attached to it as policymakers have failed to use official rates to maintain [...]

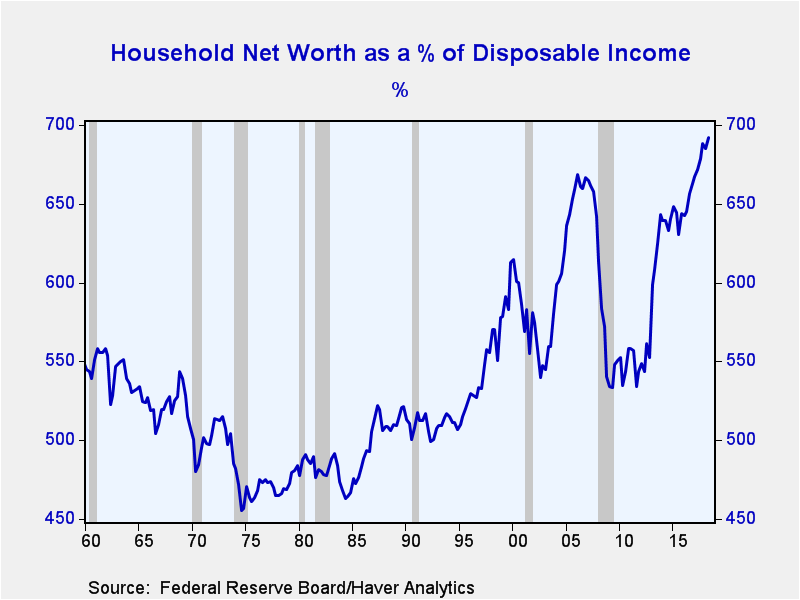

The Federal Reserve is facing the growing possibility of the third asset price bust in the last two decades. And each one has a "Made in Washington" label attached to it as policymakers have failed to use official rates to maintain financial stability while also inadvertently fueling excessive asset price gains by pursing expansionary policies to achieve their inflation-target.

The Federal Reserve is facing the growing possibility of the third asset price bust in the last two decades. And each one has a "Made in Washington" label attached to it as policymakers have failed to use official rates to maintain financial stability while also inadvertently fueling excessive asset price gains by pursing expansionary policies to achieve their inflation-target.

At this time, policymakers are between a rock and hard place; if they decide to continue to raise official rates along the path they outlined asset prices are likely to fall further, albeit from record high levels, and if they decide to pause elevated asset price levels and associated financial balances will remain a big risk for the foreseeable future. In other words, it’s a "pay me now or pay me later" decision.

From Inflation Monitoring to Inflation TargetingInflation has always been a central focus of the Federal Reserve. Yet, it the past two decades the focus has shifted from monitoring and responding to economic and financial conditions that have the potential to create inflationary or disinflationary conditions to the management of hitting a single target for a narrowly defined basket of consumer goods and services.

For example, during an 8-year stretch, from the beginning of 1994 to the end of 2001, core consumer price inflation (the Fed’s main price target) never posted one year of over 3% or one year under 2%. Despite that relatively steady price environment the Federal Reserve moved official interest rates up and down a total of 31 times, 13 of which were more than 25 basis points, and most of the moves were not telegraphed ahead of time.

Over that period, official rates were moved in response to fast growth, slow growth, strong and weak trends in commodity prices, international crises, sharp moves in currencies, abrupt shift in credit market conditions and large and sustained gains and declines in equity prices. Few recall that monetary policy was effective when it was less transparent and used official rates to respond to a diverse set of economic and financial conditions.

The policy framework started to change in the early 2000s when policymakers wanted to secure and maintain the low and stable price environment. Policymakers started to embrace the inflation-targeting practices of other central banks as the best way to secure the current low inflation rate and to anchor expectations of future inflation.

Although it was not formally adopted until years later policymakers based many their policy decisions on hitting a specific target of 2% in the published price indices. During this period, policymakers saw no conflict between inflation targeting and the preservation of financial stability, although that was more of conjecture as there was not a sufficient body of evidence to prove otherwise.

The last two decades have clearly demonstrated that excessive increases in real and financial asset prices can occur without any significant movement in the standard price measures. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon and yet nowhere in the economic textbooks does it say that an accommodative monetary policy will cause inflation to only appear in the published price indices of the federal government.

Many questions remain unanswered, but the events of past two decades have rendered one clear answer in that asset price inflation has become a permanent feature of the transmission of the current monetary policy framework of inflation targeting. Policymakers need to rethink its framework, raising the importance of its third mandate financial stability, and be willing to use official rates to maintain financial stability, or asset cycles and financial crises will continue to be "Made in Washington."

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.