Global| Feb 21 2020

Global| Feb 21 2020"Deja Vu": Companies Don't Account For All Costs To Make Financial Results Appear Better

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

A large number of US companies are relying on accounting gimmicks to strip out various costs in order to make reported profits appear to be better (or losses less small) than actually is the case. Once again the biggest adjustment [...]

A large number of US companies are relying on accounting gimmicks to strip out various costs in order to make reported profits appear to be better (or losses less small) than actually is the case. Once again the biggest adjustment appears to be for equity-based compensation and centered in the information/technology sector, very similar to what occurred in 2000.

A large number of US companies are relying on accounting gimmicks to strip out various costs in order to make reported profits appear to be better (or losses less small) than actually is the case. Once again the biggest adjustment appears to be for equity-based compensation and centered in the information/technology sector, very similar to what occurred in 2000.

Déjà Vu

In 2000, I conducted a study of stock options for the S&P 500 companies. The study was conducted in order to try to ascertain the net value of stock options for workers on the payrolls of S&P 500 companies. The net value or gain was the difference between the market price and the total employee cost of stock options. The results were stunning.

According to the research, the total market value of outstanding options as of June 30, 2000 was estimated to be $893 billion, with an employee cost of exercising all positively valued options at $323 billion. That left a net gain for all employees---management and others---of $570 billion.

Yet, as incredible as the macro numbers appeared on the surface what was even more staggering was the industry concentration. Positively valued stock options at information/technology companies were estimated to be $330 billion, 6 times larger than the next largest sector. And at the time, the total profitability of the this sector was one-tenth the size of the net value of the stock options.

It took the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) a few years to fully research the equity-based compensation issue and incorporate their findings into the profits and employee compensation data. And the revisions were large; operating profits in 2000 were reduced by $100 billion (with a large downward adjustment in the information/technology sector) while wage and salary income was revised up by over $80 billion from what was initially estimated by BEA.

Is This A Replay of 2000?

Following the release of fourth quarter earning's reports a number of analysts have commented that several firms had very large equity-based compensation adjustments in their recent earnings reports. It has become a common practice nowadays for companies to report a net income number based on standard financial accounting principles and then add back items (such as depreciation) that don't affect the companies cash position.

Yet a number companies also rely on a liberal use of accounting for equity based compensation. And as was the case in 2000 equity based compensation can result in some very meaningful adjustments---e.g. take a look at recent earnings reports from Uber, Roku, Yelp and others--- making reported numbers appear to be a lot better than they actually are in reality.

How pervasive and large are these equity-based adjustments is difficult to gauge at this point. But it is possible to get some insight by looking at GDP profits, which are based on a tax-accounting framework and include all of the actual equity based compensation costs.

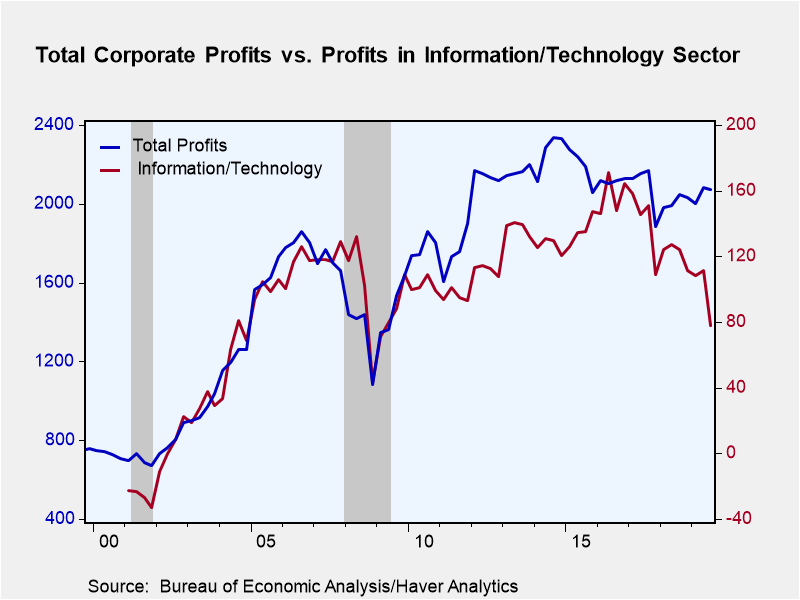

According to the GDP figures, company profits (before depreciation) have been inching lower for the past 5 years, very similar to trend in profits leading up to 2000. And one of the biggest contributors to the downtrend (similar to 2000) has been the sharp decline in profits in the information/technology sector. In fact, the latest report shows profits for this sector stood at $78 billion (before depreciation) in Q3 2019, off a staggering 55% from the cycle peak of $170.9 billion in Q3 2016.

Profits in the information/technology sector experienced a similar fate during the height of the tech-equity bubble. For example, in 1999, profits in the information/technology sector fell nearly 40% from the prior year, even when overall profits for the entire economy rose nearly 4%. Moreover, the entire information/technology sector reported operating losses in 2000 at a time when employees in this industry reaped billions in equity-based compensation.

The information/technology sector, which was reconfigured with the shift to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) in 1998, includes a diverse set of firms/industries--- including software publishing companies, data processing. telecommunications and the Internet, and consists of many of the most high-valued companies (e.g. Amazon, Apple, Google & Facebook) in the equity market and presumably some of the most profitable firms in the S&P 500.

To be fair, not all of the profit decline in the information/technology sector since 2016 can be entirely attributable to higher equity based compensation costs. But it is true that information/technology firms are some of the biggest users of equity-based compensation to attract and retain employees.

Critics might argue that equity based compensation is not a cash expense. But all forms of employee compensation should be treated equally. To be sure, if companies sold stock (or options) in the market and then used the cash proceeds to pay its employees it would be treated as a cash expense. In the end, equity based compensation is a cost (or transfer) of income from shareholders to employees and should be treated as an cash expense.

March 10, 2020 marks the 20-year anniversary of the tech equity bubble. There were many factors behind the bursting of the tech bubble. But at the center investors expectations over current and future (or dream) earnings proved to be far too high, while actual earnings were far below what many believed them to be. Once again actual profits are running below that of reported profits and its just a matter of time before there is a reset of earnings expectations for investors.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.