Global| May 17 2021

Global| May 17 2021Fed Is Promoting A Public Perception of Inflation That is False----Bad Outcomes Follow Bad Policies

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

Federal Reserve officials have made a bold claim arguing that the current run-up in consumer price inflation is "transitory," pushed higher due to base effects and a temporary burst in pent-up demand as the economy re-opens. The Fed [...]

Federal Reserve officials have made a bold claim arguing that the current run-up in consumer price inflation is "transitory," pushed higher due to base effects and a temporary burst in pent-up demand as the economy re-opens. The Fed has no unique insight into inflation dynamics. Puzzlement over inflation dynamics has been a recurring problem for policymakers for more than two decades, and it still is today.

Federal Reserve officials have made a bold claim arguing that the current run-up in consumer price inflation is "transitory," pushed higher due to base effects and a temporary burst in pent-up demand as the economy re-opens. The Fed has no unique insight into inflation dynamics. Puzzlement over inflation dynamics has been a recurring problem for policymakers for more than two decades, and it still is today.

Yet what is puzzling and misleading about policymakers' current take on inflation is that it ignores the monetary role in inflation cycles. And equally puzzling and deceptive is calling the inflation cycle "transitory."

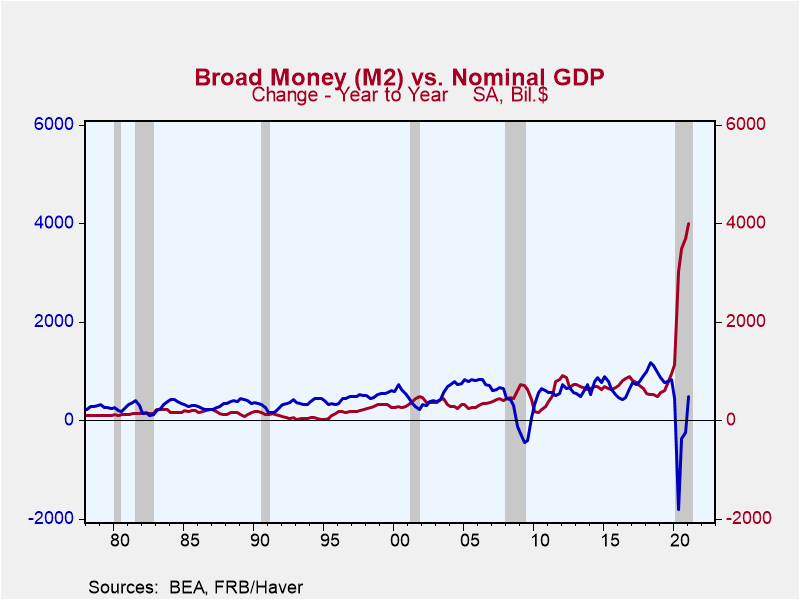

The Fed's primary business is making money, and that's important because the Fed maintains "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." In the past year, broad money (M2) has increased by $4 trillion, or over 20%. The scale of growth in broad money has been so large it exceeded the cumulative change in M2 of the prior five years. Never before has so much money flowed into the economy in such a short time frame.

Yet, nowhere in the analysis of current inflation does the Fed link the explosion of money to inflation. The most significant mismatch nowadays is between money growth and nominal GDP, but the Fed still argues that the current inflation uptick is because of a temporary burst in demand overwhelming supply.

Another problem with the Fed's discourse on inflation is calling it "transitory." There is no hard and fast rule when something initially thought to be temporary becomes a permanent part of the economic landscape. But a rebound that lasts four times longer and is not yet finished than the temporary event is more permanent than transitory.

When the economy was partially closed from March to May 2020, core consumer prices declined in each of the three months, falling less than 0.5% in total. Since then, core consumer price inflation has increased for 11 consecutive months, increasing 3% during that span, the fastest gain in nearly three decades. Why is an 11-month increase of 3% in inflation called "transitory" but a three-month decline of 0.5% not?

Henry Kaufman, the famous Wall Street economist, recently published a book, "The Day the Markets Roared," based on how his 1982 forecast of a decline in market interest rates sparked a global bull market. Wouldn't it be ironic that forty years later that a change in the Fed description or forecast on inflation would trigger a global rout in finance? Promoting a public perception of inflation that is false creates the potential for bad outcomes.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.