Global| Jan 22 2020

Global| Jan 22 2020Monetary Policy & Business Cycle Scripts Have Changed: Fed Policy Stimulates Finance Over Spending

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

The monetary policy guide has fundamentally changed and so to has the business cycle. Changes in monetary policies and practices nowadays stimulate finance over spending. The power and risks of equity markets should not be overlooked [...]

The monetary policy guide has fundamentally changed and so to has the business cycle. Changes in monetary policies and practices nowadays stimulate finance over spending. The power and risks of equity markets should not be overlooked as important metrics show equity valuations to be 2X times their historical norm.

The monetary policy guide has fundamentally changed and so to has the business cycle. Changes in monetary policies and practices nowadays stimulate finance over spending. The power and risks of equity markets should not be overlooked as important metrics show equity valuations to be 2X times their historical norm.

Monetary policy can stimulate too much finance (equities) as it did with spending (inflation). As such, the risks of business cycles have shifted toward finance and away from inflation.

Here are 5 examples of how monetary policies, new tools and practices stimulate finance over spending.

Policy Rates: The primary tool of monetary policy is the target on the federal funds rate. Policymakers have often struggled to find a good balance, or find a rate that was equally good for the economy and finance.

Policymaker's promise to keep official rates exceptionally low in recent years, and now for the foreseeable future, clearly favor finance over spending. To be sure, interest rates are the most important item in determining the value of equities so the promise on official rates creates the "perfect knowledge" market theory for investors since it eliminates one of the key risks and unknowns---the current and future level of official rates.

Policy Bias: Policymakers have consistently shown a bias to ease policy during sharp sell-offs in the financial markets and no bias to withdraw liquidity when finance races far ahead of the economy. This uneven policy ---often call the "Fed put"---creates the impression in the minds of investors that policymakers will always ride to their rescue during sell-offs and not stand in the way when markets boom.

Policy actions of 2018 and 2019 clearly demonstrate that the policy bias is alive and well. Policymakers canceled their plans to raise official rates in 2019, following the abrupt and sharp equity market sell-off in Q4 2018, and yet show no inclination to take back any or all of the three rates cuts of late 2019 despite the resurgence in equity markets to new record highs.

Asset Purchases: The Federal Reserve has become a big investor in financial assets, expanding the Feds balance sheet to $4.5 trillion at its peak, up from less than $900 billion before the financial crisis. The new Fed tool works through the portfolio channel, injecting more liquidity into the financial markets, thereby lifting the price of financial assets, while also signaling to investors an easier stance on monetary policy.

The recent selloff and rebound in the equity markets have been highly correlated with the shrinkage and the renewed expansion of the balance sheet in 2018 and late 2019. Rightly or wrongly investors view increases and decreases in the Fed's balance sheet as a signal of easy or tight money and a risk-on or risk-off strategy.

Transparency and Forward Guidance: Policymakers now telegraph their decisions on policy rates, well ahead of any actual decision and also offer forward guidance on policy rates along with their economic forecasts. Who benefits from greater transparency and forward guidance?

Investors appear to be the big winner. Never before did policymakers offer so much transparency on official rates---telling investors what they plan to do, when and by how much. That's not to say policy transparency has taken all of the risk out of investing, but it removed one of the biggest risks, enabling investors to devise a series of investment strategies based on "inside" knowledge on official rates.

Price Targeting: The Fed elevated inflation from an objective of monetary policy to an actual target. That might not sound like a big deal, but it is.

The curious thing about price targeting is the gauge policymakers chose to target. The Fed picked the personal consumption expenditure deflator (PCE) over the more widely used consumer price index (CPI). PCE consistently runs below the CPI, so by selecting the PCE there is a clear bias towards lower rates.

In 2019, the choice of the price index proved to be the difference between easing and tightening policy. To be sure, the core PCE reading of 1.7% tilted policy towards an easier stance, while the CPI of 2.3% favored rates inching up a bit more.

The Results

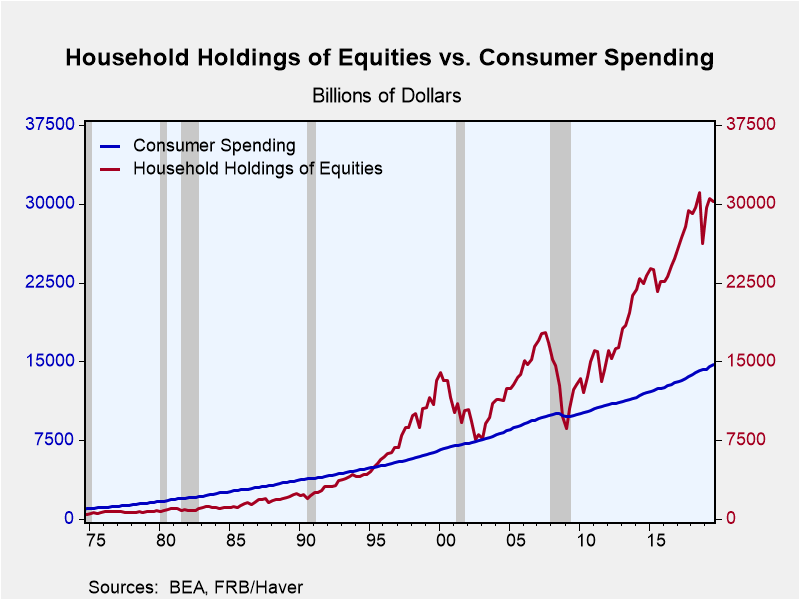

The numbers on finance (equity valuations) are impossible to ignore. Household holdings of equities stand nearly 2X times the level of consumer spending as does the market valuation of domestic companies to nominal GDP. Historic norms are closer to 1X.

The narrow public ownership of equities limits the spending impulse for consumers, but the high equity valuations offer companies a huge collateral buffer to borrow. US nonfinancial companies are sitting on over $10 trillion in debt, almost twice as much as what was on corporate balance sheets at the end of the 2008, and the highest debt-to-sales ratio on record.

From many angles, monetary policy nowadays stimulates finance more than spending and as the equity market goes so goes the business cycle.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.