Global| Dec 09 2020

Global| Dec 09 2020Mr. Magoo's Bull Market: Investors Pay More For Growth & Worry Less About Debt

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

The world of finance changed in 2020. Investors nowadays are willing to pay more for growth and worry less about debt. Changes in investment philosophy and practices are directly related to the actions of the Federal Reserve. Fed [...]

The world of finance changed in 2020. Investors nowadays are willing to pay more for growth and worry less about debt. Changes in investment philosophy and practices are directly related to the actions of the Federal Reserve.

Fed policies of near-zero official rates, buying record amounts of government and corporate debt, and the promise of no rate increases for an indefinite period has created an investor mindset of endless gains and little risk.

Decades of investing rules and practices are not repealed and remade in a single year. The unusual events and outcomes in the world of finance in 2020 create new tipping points. Mr. Magoo’s Bull Market is not sustainable.

Changes In Finance---Equities

The equity market had a lot of firsts in 2020. The S&P 500 will register a double-digit gain during a recession year. That might not sound like a big deal, but it is.

During the recession year of 2008 S&P 500, the S&P 500 posted a 38.5% decline; in 2001 equity prices fell 13%, and in 1990 equities dropped 6.6%.

Another first is the record high valuation of equities relative to nominal GDP. At the end of Q2, the ratio of the market valuation of domestic equities to Nominal GDP topped 2X times, a record high for the post-war period, exceeding the prior record of 1.9X times during the tech bubble.

At current market levels, the S&P 500 price-to-earnings ratio stands at 30, a record high. And that's before Tesla, which has a P/E ratio over 1200, is added to the S&P 500 index. Press reports indicate that the addition of Tesla would lift the P/E multiple by several percentage points.

The historic average P/E ratio is around 15X times. In other words, investors were paying for 15 years of annual profits. An average economic growth cycle runs about 60 months or 5 years. So in the past investors were willing to pay for three growth cycles, but today they are so confident they are paying for 6.

The debt markets had a lot of firsts in 2020. Businesses added to outstanding debt levels instead of paying down debt as have been the common practice during past recessions. Based on market data, non-financial corporate debt has increased by more than $1 trillion during 2020, lifting the outstanding level to more than $11 trillion.

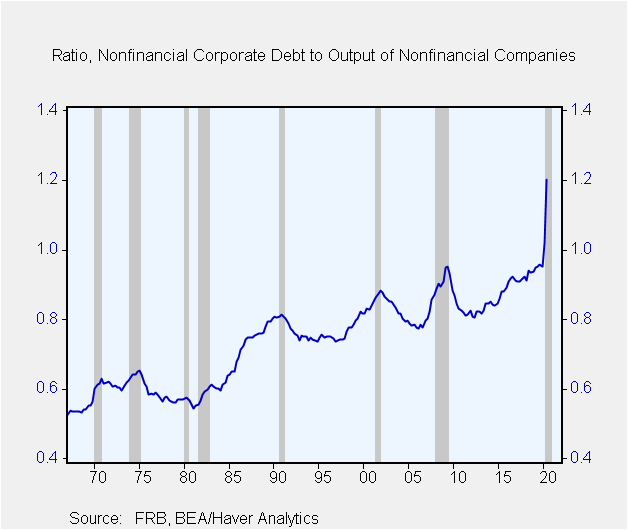

At the end of Q2, the ratio of nonfinancial debt and loans to the nominal output of nonfinancial corporate businesses stood at 1.2X times. That's a record high, and 25 percentage points higher than the worse levels of the Great Financial Recession.

Nonetheless, investors seem to be unfazed by record debt levels. The average yield on investment-grade corporate debt currently stands at 1.85%, a record low.

The level of debt to earnings and cash flow used to be an important investment metric. Nowadays the burden of debt is looked at mainly through the lens of servicing it (i.e. interest payments) instead of paying it. While it is true low-interest rates reduce debt-servicing costs it does not lower the debt burden or eliminate the risks of high debt levels.

Investors act like the investment protocol of 2020 represents permanent change. The contrarian in me tells me it's not. Mr. Magoo's Bull Market is not sustainable and the big risk is that policymakers use the events and outcomes of 2020 to justify more government involvement in finance thereby creating new tipping points for the economy.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.