Global| Jul 24 2018

Global| Jul 24 2018Something Missing: Yield Curve Signal Not Confirmed Elsewhere

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

A lively debate has broken out over the narrowing of the yield curve, or the spread between short and long-term Treasury yields. In fact, some Federal Reserve officials have stated that they might want to stop raising official rates [...]

A lively debate has broken out over the narrowing of the yield curve, or the spread between short and long-term Treasury yields. In fact, some Federal Reserve officials have stated that they might want to stop raising official rates in order to avoid the possibility of inverting the yield curve since curve inversion has been a harbinger of recession.

A lively debate has broken out over the narrowing of the yield curve, or the spread between short and long-term Treasury yields. In fact, some Federal Reserve officials have stated that they might want to stop raising official rates in order to avoid the possibility of inverting the yield curve since curve inversion has been a harbinger of recession.

Statistically, the yield curve has been a leading indicator of economic recession, but why is it? Is there something inherent in the yield curve that makes the economy reverse course?

Yield curve inversion has almost always occurred when the Federal Reserve was raising official rates in order to retard or reverse a rise in general inflation or economic conditions that potentially could lead to an unwanted rise in inflation. That is not the case today as the Federal Reserve is trying to encourage a rise in inflation in order to meet their price stability target.

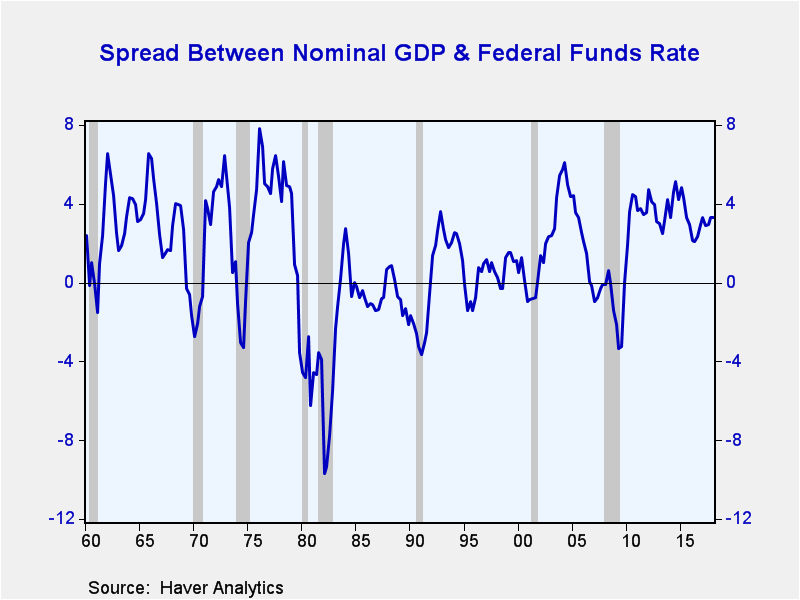

What is often missed in the analysis of the yield curve is that as powerful as it signal has been its always coincided with an inversion in the economy’s yield curve---or the spread between the growth in nominal income and interest rates.

Unlike the Treasury yield curve there are direct consequences when the interest rates rise above the economy’s growth rate. To be sure, in time new borrowing becomes too costly which eventually leads to a slowdown in lending and spending. Also, to the extent that finance costs on past borrowings are not fixed a rise in interest rates would also lift interest costs on outstanding loans further draining cash flow.

At this point in the cycle the economy’s yield curve is not only positively sloped, but the spread between nominal GDP and the federal funds rates is very wide sending a positive signal on the economic outlook. To be sure, based on consensus forecasts the year on year growth for Q2 Nominal GDP (scheduled to be released on July 27) is estimated to be 5.3% or well over 300 basis points over the current target on the federal funds rate, and roughly unchanged since the start of the year.

Because of the changing nature and causes on business cycles as well as the changing policy tools of the Federal Reserve it is always necessary to rely on a group indicators to help forecast and anticipate changes in the economic outlook. Relying on a single indicator, even one with a stellar record like the yield curve, runs the risk getting a false or misleading signal especially since the Federal Reserve has been directly trying to control the yield curve in the current cycle.

Policymakers would be well advised to look a broad array of indicators since in this case the economy’s yield curve and the market yield curve are sending conflicting signals and the risk of being too easy in light of exceptionally high asset values and stimulative fiscal policy seems to a bigger risk than being too tight.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.