Global| Jan 03 2020

Global| Jan 03 2020Two Equity Market Booms, Two Policy Paths

|in:Viewpoints

Summary

In the past two decades there have been two fundamentally different types of equity market booms that resulted in the market valuation of US companies relative to Nominal GDP soaring to equivalent record highs. Yet, during the dot.com [...]

In the past two decades there have been two fundamentally different types of equity market booms that resulted in the market valuation of US companies relative to Nominal GDP soaring to equivalent record highs.

In the past two decades there have been two fundamentally different types of equity market booms that resulted in the market valuation of US companies relative to Nominal GDP soaring to equivalent record highs.

Yet, during the dot.com boom monetary policy “leaned against the wind” whereas during the current equity market boom monetary policy has opted to “go with the wind”.

Easy money policy can extend the life cycle of an equity boom, but at the risk of greater financial instability at some point for the simple reason easy money can trigger speculation and over-valued assets since it does not increase the economy’s long-term growth rate or the profitability of companies.

Two Equity Market Booms

The US equity markets soared in 2019, with broad stock averages posting gains of 25% to 30%, extending a long advance in equity prices. The surge in equity prices lifted the market valuation of domestic companies by estimated record $9 trillion over the course of 2019, pushing the total valuation to approximately $40 trillion at the end of 2019.

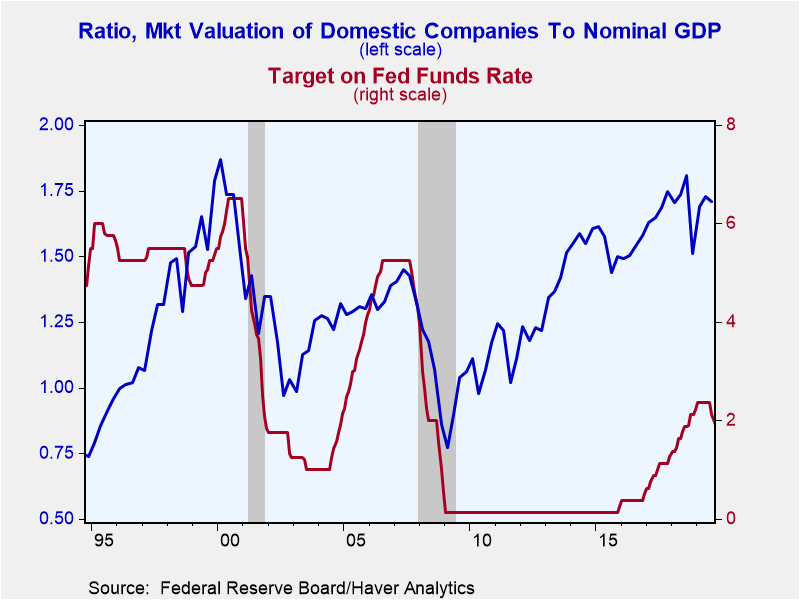

Measured in relation to Nominal GDP---a well-known metric to assess the over-or-under valuation of the overall stock market---the market valuation of domestic companies stood at 1.85X at the end of 2019, near the upper end of its long run average.

A similar level of the market valuation of domestic companies to Nominal GDP occurred at the end of the dot.com boom. Fueled by speculation that a new business model (internet) would result in large gains in future profits investors’ poured huge sums of money into new start-ups driving 20% to 30% gains in the broad equity markets for five consecutive years. At the peak of the tech boom in

Q1 2000 the market valuation of domestic companies to Nominal GDP stood at a record high of 1.86x---a level that appears to be reached again at the end of 2019.

The dot.com equity boom of the late 1990s and the current equity market boom have little in common. To be fair, powerful common elements of liquidity and optimism about future profits are key factors in both cycles, but the dot.com liquidity engine was not sourced by easy money, whereas the current equity cycle is.

Two Policy Paths

During the dot.com boom the target of the federal funds rate averaged 5.5%, with a range of 4.75% to 6.5%, running 250 to 300 basis points over underlying inflation. Compare that to the zero to 2% target of fed funds for the past several years, and a fed funds rate that consistently ran below underlying inflation.

And, most importantly, the different monetary policy regimes are most extreme at the highest points of the relative market valuations. To be sure, at the peak valuation of the dot.com equity boom in 2000 policymakers were raising official rates, or “leaning against the wind” trying to dampen the wealth effect in the economy. Compare that to 2019 when policymakers faced with similar jobless and underlying inflation stats of 2000, decided to lower official rates, or in other words, “go with the wind”.

In reality, monetary policy can contribute to an equity market boom by holding rates low, or cutting them as what occurred in 2019, causing investors to demand less compensation for risk, inflating the prices of assets in the process. Yet, historical evidence is unambiguous that easy money contributes nothing to long-term economic growth or operating profits of companies, but can and has triggered financial instability.

Presiding over one stock market boom (and bust) that was not fueled by easy money could be seen as bad luck. But presiding over a second one that is fueled by easy money smacks of negligence since one of the mandates of monetary policy is to ensure financial stability.

Policymakers appear to be in no rush to reverse the policy actions of 2019 so the current equity bull market will continue to run for a bit more. Yet, the odds of a policy mistake are rising and the safety valve of easy money for the equity market is limited as well. And if history proves to be a reliable guide the peak in the market valuation of domestic companies to Nominal GDP has already occurred since its unlikely that company profits will be able achieve the lofty expectations of investors.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Joseph G. Carson

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Joseph G. Carson, Former Director of Global Economic Research, Alliance Bernstein. Joseph G. Carson joined Alliance Bernstein in 2001. He oversaw the Economic Analysis team for Alliance Bernstein Fixed Income and has primary responsibility for the economic and interest-rate analysis of the US. Previously, Carson was chief economist of the Americas for UBS Warburg, where he was primarily responsible for forecasting the US economy and interest rates. From 1996 to 1999, he was chief US economist at Deutsche Bank. While there, Carson was named to the Institutional Investor All-Star Team for Fixed Income and ranked as one of Best Analysts and Economists by The Global Investor Fixed Income Survey. He began his professional career in 1977 as a staff economist for the chief economist’s office in the US Department of Commerce, where he was designated the department’s representative at the Council on Wage and Price Stability during President Carter’s voluntary wage and price guidelines program. In 1979, Carson joined General Motors as an analyst. He held a variety of roles at GM, including chief forecaster for North America and chief analyst in charge of production recommendations for the Truck Group. From 1981 to 1986, Carson served as vice president and senior economist for the Capital Markets Economics Group at Merrill Lynch. In 1986, he joined Chemical Bank; he later became its chief economist. From 1992 to 1996, Carson served as chief economist at Dean Witter, where he sat on the investment-policy and stock-selection committees. He received his BA and MA from Youngstown State University and did his PhD coursework at George Washington University. Honorary Doctorate Degree, Business Administration Youngstown State University 2016. Location: New York.