Global| Jan 28 2008

Global| Jan 28 2008Money Growth

Summary

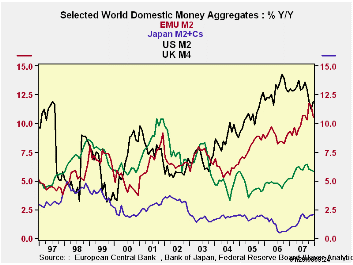

On the face of it money supply growth should not give us much cause to fear recession. The US and UK show slowdowns in high frequency growth rates of money supply but only the US three-month rate is a negative one; and three-month [...]

On the face of it money supply growth should not give us much

cause to fear recession. The US and UK show slowdowns in high frequency

growth rates of money supply but only the US three-month rate is a

negative one; and three-month growth rates are often more volatile than

indicative. Japan’s pace of money growth is mostly steady at a low

rate. Money growth rates do not seem to be a place to find a reason to

fear an economic recession either in the US or in Europe.

The Euro area. The Euro area is posting huge growth

rates in money and key credit aggregates; those growth rates remain

bloated even when deflated by the headline HICP. EMU loan growth slowed

over the past year compared to the past three years' average;

inflation-adjusted, the slowing is more pronounced from near 12% to

7.5% over the past year and to 2.7% over the last three months

annualized. Residential real credit slowed from its three-year pace but

has not slowed over two years when its growth has remained too-strong

just short of 13%. Inflation-adjusted, there has been a bit more

slowing in residential credit but not much. The three-month growth rate

in fact tells us that for residential borrowers there has been little

retraction in Euro credit at all. The overall pace for loans has slowed

from its three-year pace but the two-yea and one-year rates of growth

are still steady and high. The three-month nominal pace has slowed to

around 8% from near 11% but the real slowing is in the

inflation-adjusted figures. There, loan growth is seen down from 11.9%

over three years to 5.3% over two years back up to 7.5% over the past

year then with a sharper slowing over six months and three months to a

low three-month rate of 2.7%. This slowdown in overall credit suggests

that there is some slowing in credit outside the residential sector in

Europe. Still the 3-month growth rate in credit above the rate of

inflation is substantial. It does not seem to be the sort of thing to

bring on recession. But the downward shift in the rate of growth in

real credit may be indicating a slowing in growth.

The US. In the US nominal money growth slowed over

two-year and one-year horizons compared to three years but has seen

otherwise quite stable growth rates at around 5.5%. Real balances have

slowed much more and are registering negative growth over three months.

US real GDP growth has been outstripping what money supply would have

allowed in the US with constant money velocity. If velocity fails to

expand (velocity is the inverse of the money to GDP ratio) the economy

does seem set for a slowing. The recent negative real money growth rate

is mild warning, but it is only a three-month figure and so is

indicative, not demonstrative. The year/year growth of real balances at

1.7% is appropriate for a period when headline inflation has overshot

and oil prices have threatened to extend inflation’s push into the core

rate of inflation. ‘Money supply policy’ or at least the result seems

broadly in line.

The UK. In the UK money supply nominal and real

slowdowns are like those in the US only more severe. The rate of money

growth in the UK remains higher than in the US but the deceleration is

sharper and may be more of a factor in adversely affecting growth there

in the short run.

Japan. Japan’s money growth has been low and steady.

After inflation adjustment real money balances are lower but are just

skimming above the unchanged level.

Summing up. On balance, Central banks seem to been

relatively reserved during this period when oil prices have flared. The

ECB makes pointed references to money supply and credit in its policy

deliberations and it has been uncomfortable with what it has been

seeing for some time. The BoE and BoJ also use monetary references. The

Fed makes policy without much reference at all to money supply and has

even abolished a monetary aggregate (M3) in recent years. While

financial market innovations may have made it harder to measure what

economists mean by ‘money’ the monetary definitions offered up by

central banks are for the most part growing and do not look to have

created much in the way of special growth problems for the recent

quarters. Japan continues with low but stable real balance growth and

nominal money growth. The UK has the largest deceleration in money

growth rates. The US has a three-month shift to a negative real balance

growth rate, too short a period to be taken as definitive on

illiquidity. The ECB’s aggregates remain above its tolerance levels as

does its inflation rate. But the squeeze in Europe, if there is one, is

on businesses not on households or the consumer.

| Look at Global and Euro Liquidity Trends | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saar-all | Euro Measures (E13): Money & Credit | G-10 Major Markets: Money |

Memo | ||||

| €€ M2Supply | Credit: Residential |

Loans | $US M2 | ££K M4 | ¥¥Japan M2+CDs |

OIL: WTI | |

| 3-Mos | 11.3% | 13.7% | 8.2% | 5.3% | 7.0% | 2.6% | 77.5% |

| 6-Mos | 11.1% | 12.8% | 10.0% | 5.6% | 10.6% | 1.4% | 84.8% |

| 12-Mos | 10.6% | 12.8% | 10.8% | 5.9% | 11.9% | 2.0% | 46.8% |

| 2-Year | 6.5% | 12.2% | 10.7% | 5.5% | 12.3% | 1.4% | 24.2% |

| 3-Year | 14.7% | 17.6% | 16.0% | 7.7% | 19.2% | 2.3% | 45.1% |

| Real Balances deflated by Own CPI. Oil deflated by US CPI | |||||||

| 3-Mos | 5.6% | 7.9% | 2.7% | -0.3% | 2.2% | 0.2% | 68.0% |

| 6-Mos | 7.3% | 8.9% | 6.2% | 2.2% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 79.0% |

| 12-Mos | 7.3% | 9.5% | 7.5% | 1.7% | 9.6% | 1.3% | 41.0% |

| 2-Year | 4.8% | 6.2% | 5.3% | 1.4% | 6.3% | 0.6% | 13.0% |

| 3-Year | 10.7% | 13.5% | 11.9% | 2.5% | 15.2% | 2.2% | 38.1% |

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates