With the December report, Germany’s production and some of the early European industrial production data reveal a good deal of chaos in terms of the embedded trends. On the month, German industrial production fell by 1.9%, with consumer goods output up by 0.5%, capital goods output falling by 5.3%, and intermediate goods output falling by 1.2%. Among the early reporters in the monetary union—France, Spain, and Portugal—only Spain showed an increase in manufacturing IP in December; however, Spanish industrial production is notoriously volatile.

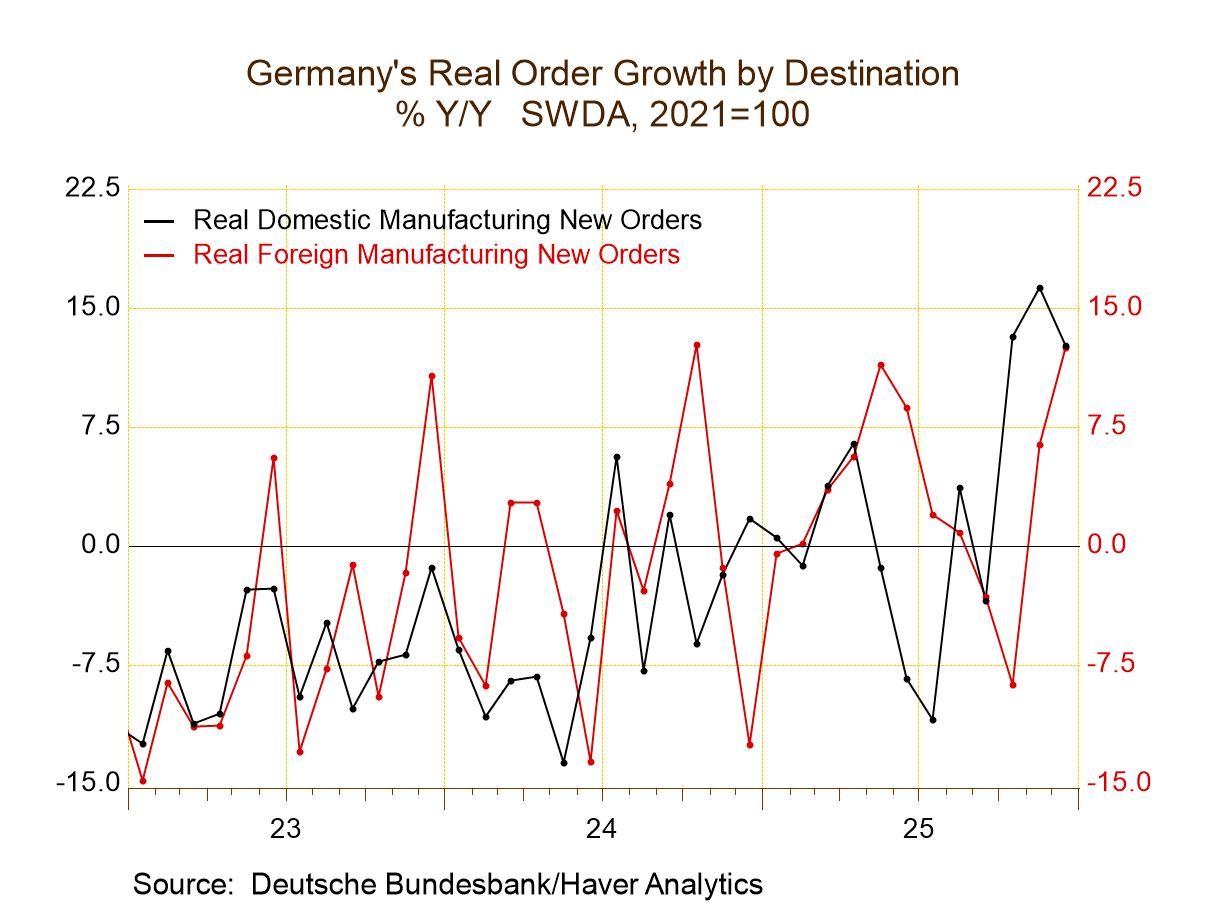

Broader IP trends in Germany and elsewhere in Europe As for other early industrial production reporters, both Sweden and Norway showed strong-to-solid gains in December and each of them showed two-months of gains in a row. Beyond that, sequential growth rates from 12-months to six-months to three-months show accelerating growth in German consumer goods output against decelerating growth for intermediate goods. Real manufacturing output and real sales show mixed results- no clear trends; however, real manufacturing orders in Germany are off the map strong.

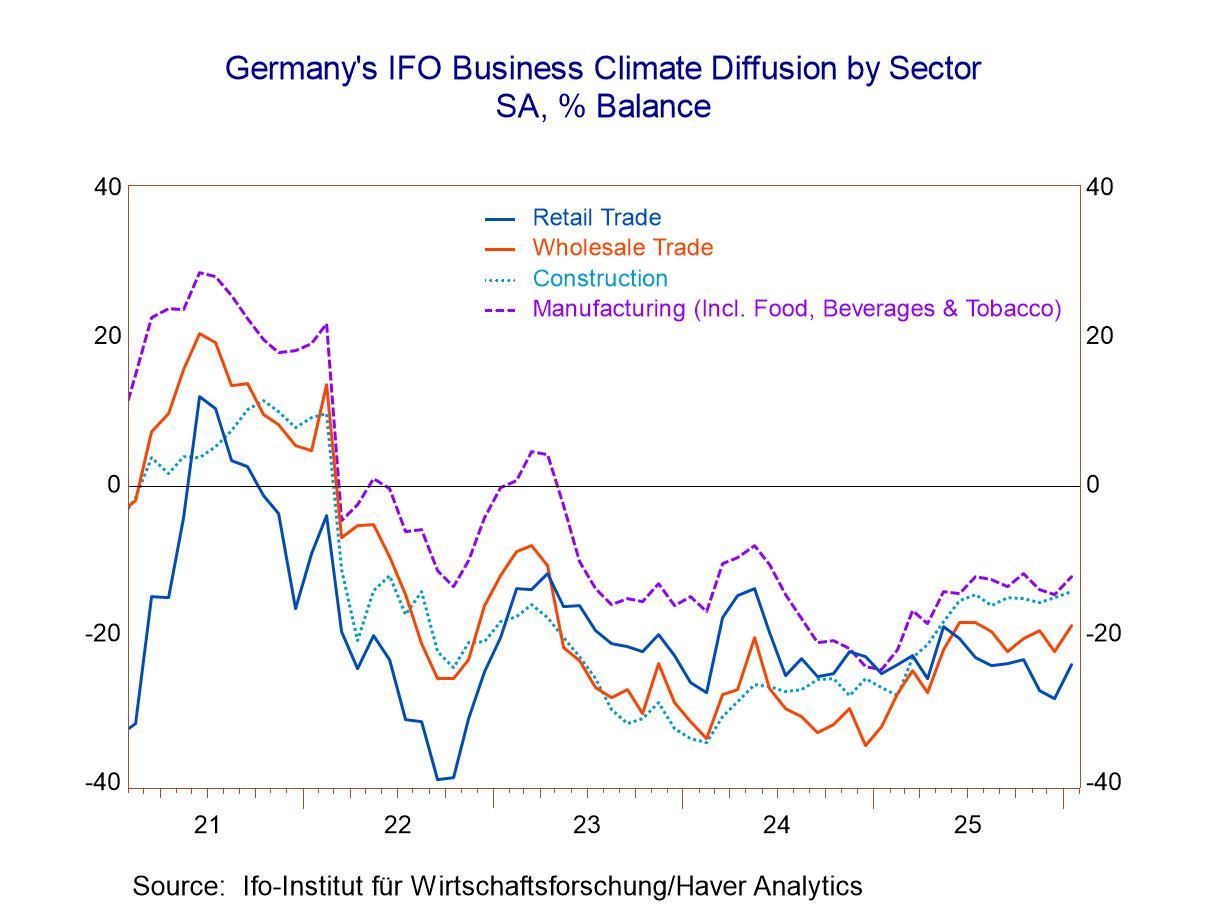

German manufacturing/industrial Surveys German industrial surveys from the IFO for manufacturing shows persistent weakening as well as for IFO manufacturing expectations, and in the EU Commission industrial index in the last three months. More broadly, Germany shows some modest but ongoing step up all of these based on average levels from 12-months to six-months to three-months for IFO expectations and the EU Commission industrial readings with mixed results for other survey readings.

IP trends in Europe For the early reporting EMU members France, Spain, and Portugal, who report industrial production trends, each show mixed monthly trends against ongoing decelerations for manufacturing output over the broader sequential periods (12-month, to 6-month, to 3-month). However, for other Europe, Sweden and Norway, manufacturing trends are steadily accelerating on this broader timeline.

A feeling of ‘Deja- What?’ These combinations of opposed trends mixed with a lack of trends leave us with this sense of confusion about what's going on in manufacturing. For Germany, the extreme strength in orders is reassuring since orders should be forward-looking rather than backward-looking or even contemporaneous. But orders can also be a fickle series and so we'll have to watch it to see if the trends for German orders hold up.

Current quarter-What’s been happening now In addition, current quarter growth for Germany actually looks quite good with industrial production up 3.7% at an annual rate in the current quarter, led by output increases in manufacturing against a decline in the intermediate goods output. Real orders in the quarter are surging at a 44% growth rate, while real sales in manufacturing only had a 0.1% uptick at an annual rate. The industrial indicators for Germany in the quarter show weakness or flatness with the only exception being IFO manufacturing expectations that advanced by a small amount. The three EMU members who report industrial production data show positive growth in the just-completed quarter except for Portugal where industrial production is falling at a 2.9% rate in the fourth quarter. Sweden and Norway, European countries but not monetary union members, show a strong 22% annual rate gain in Sweden against the 3% annual rate decline in Norway.

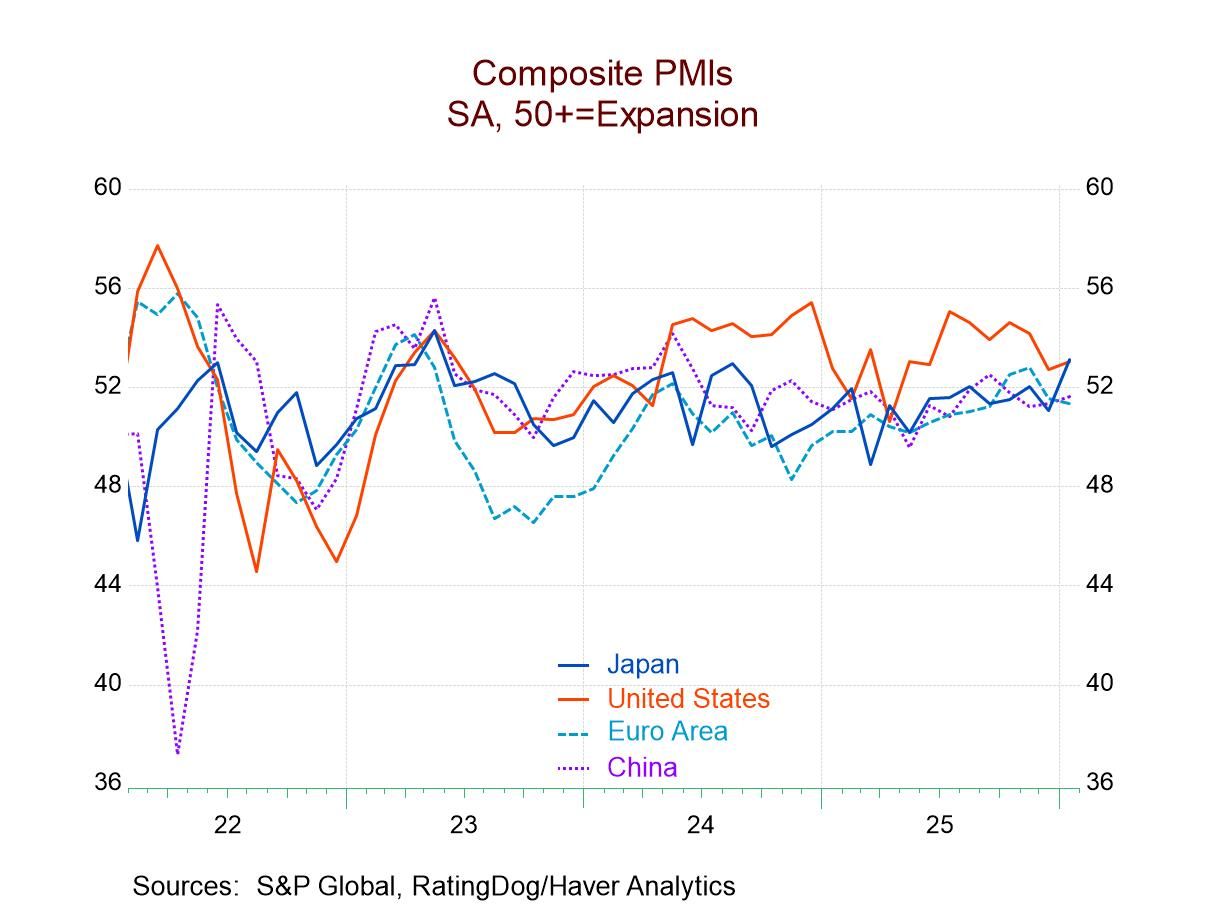

Global

Global