Global| Jun 07 2021

Global| Jun 07 2021Vaccines, Capex and China Now Hold the Key

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Economy in Brief

Summary

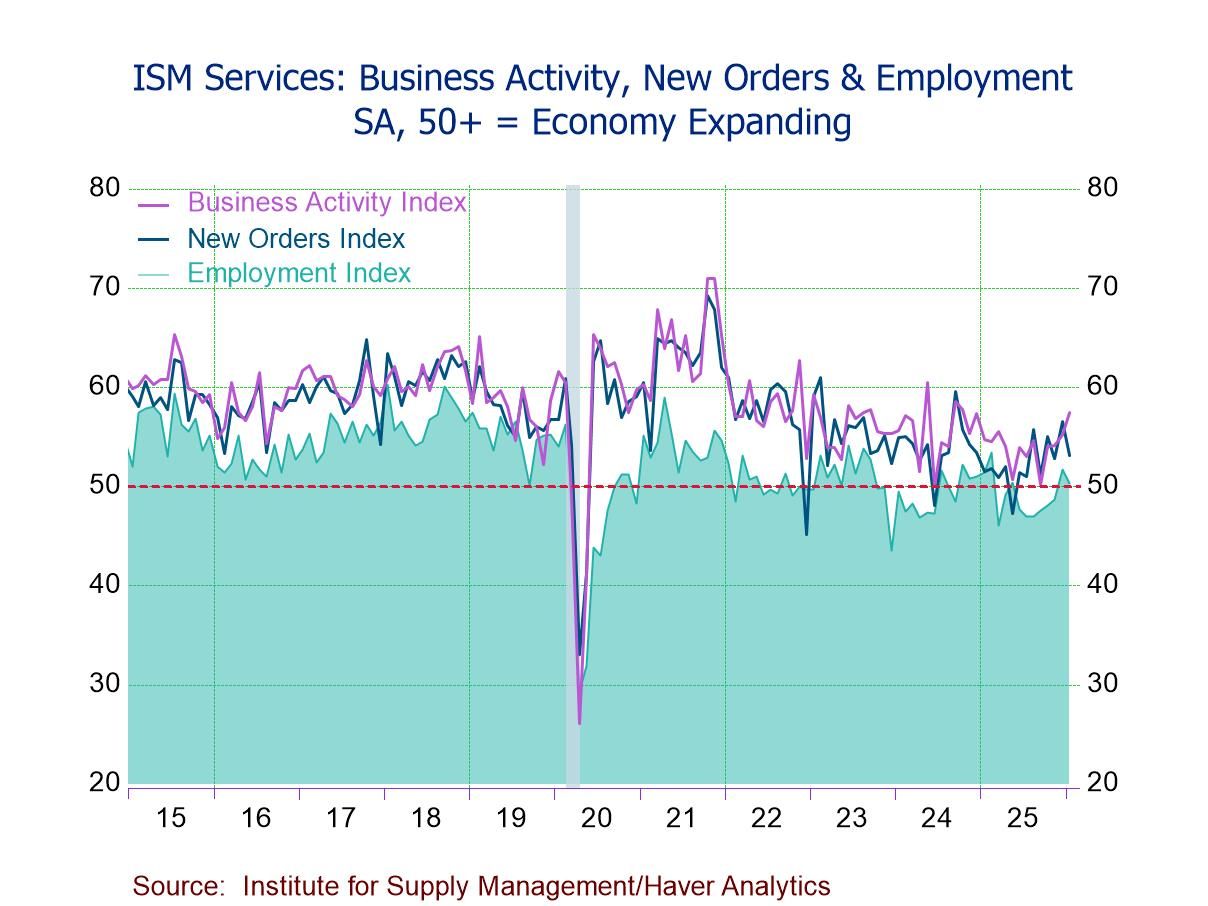

The incoming economic data over the past few days have – on the whole - painted a bright picture of the world economy. May's purchasing managers surveys for the US and Europe, published last week, suggested a broadly based improvement [...]

The incoming economic data over the past few days have – on the whole - painted a bright picture of the world economy. May's purchasing managers surveys for the US and Europe, published last week, suggested a broadly based improvement in economic activity among a number of countries and sectors has been unfolding. Last Friday's US employment report validated that message by exhibiting a decent pick up in labour market activity in May, notwithstanding some disappointment in the aggregate payroll figures. Multi-year highs for South Korea's export growth in May added further resonance to the idea that the world economy is picking up a good head of steam.

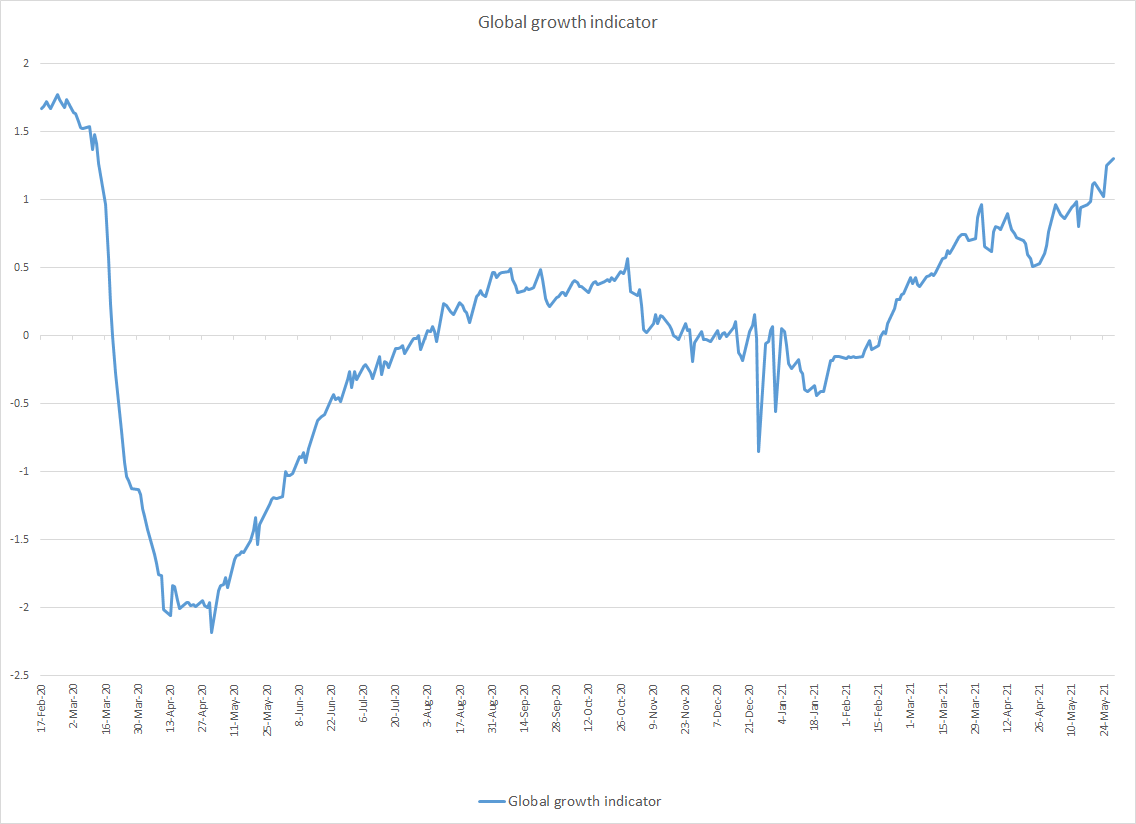

Less conventional high frequency data reinforce this message. In figure 1 below we have plotted daily data from mid-February 2020 to end-May 2021 for a newly calculated global growth indicator. This comprises three component series concerning trends in population mobility, job postings and restaurant dining activity. Great care needs to be taken in interpreting this indicator as the baselines for each series differ and the numbers are not seasonally adjusted. Still, that our indicator has climbed to its highest level since March last year, and is now not too far shy of its pre-COVID peak, endorses the idea that the world economy has been healing quite rapidly.

Figure 1: Global growth indicator – from alternative data

Source: Google, Indeed, Open Table, Haver Analytics. This indicator is an unweighted normalised average of three component series concerning trends in mobility, job postings and restaurant dining. Global mobility trends are calculated from unweighted normalised averages of Google's retail and recreation data for the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK, Canada and India. Global job postings data are calculated from unweighted normalised averages of Indeed's labour market data for the US, Canada, France, Germany and the UK. Global dining data is calculated from Open Table's global aggregation of restaurant dining trends, in turn derived from data for the US, Canada, Germany, the UK, Australia, Mexico, and Ireland. Care needs to be taken in interpretation as baselines differ across component series.

Nevertheless, while all these data is yielding upbeat aggregate signals about global economic performance if we dig a little deeper there are some trends that are more troubling. Three trends in particular stand out.

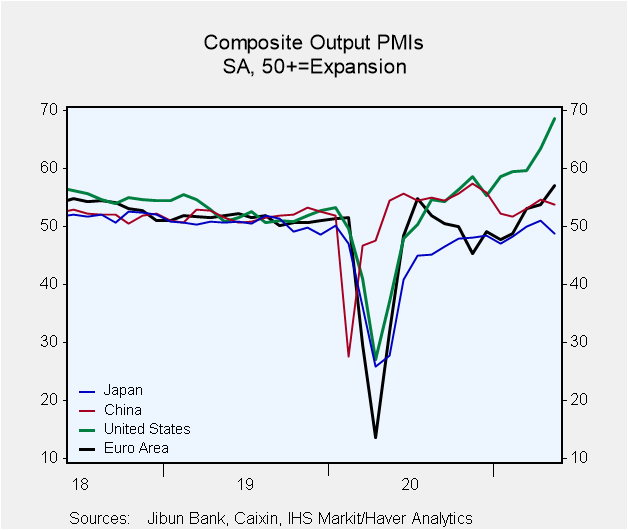

Firstly, the global recovery is somewhat uneven outside of the US and Europe. While last week's Purchasing Managers' surveys offered upbeat signals for those areas, the messaging was less promising for others, including Japan and China (see figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Manufacturing PMIs in the Euro Area, Japan and China

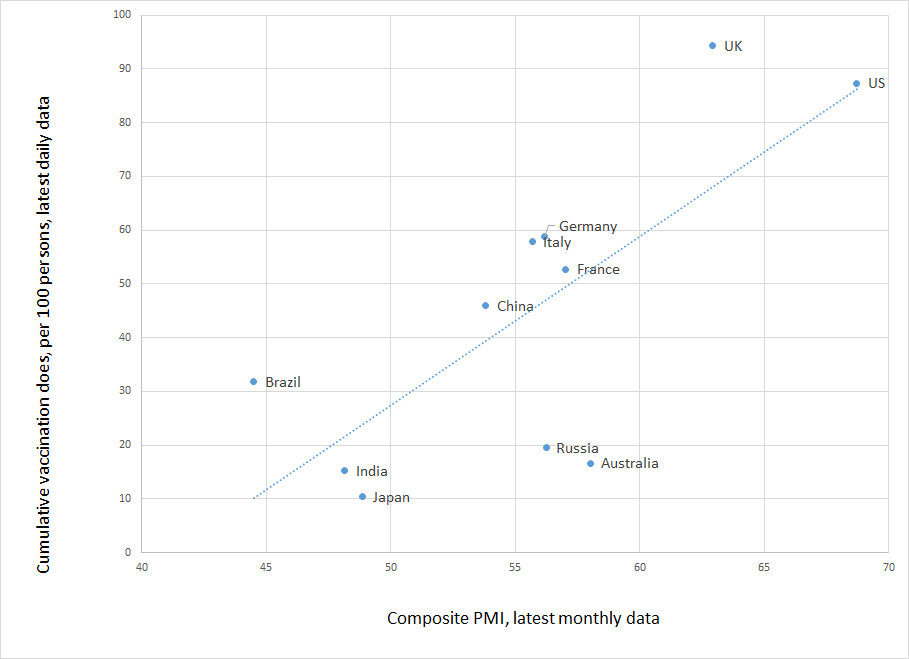

One reason for this uneven performance appears to be rooted in vaccination rollouts. Those countries that have delivered vaccines at a relatively rapid clip in recent months, such as the US and UK, have chalked up impressive gains in PMI indicators. On the other side of that equation, however, countries that have been slower to rollout a vaccination programme, such as Brazil, India and Japan, have chalked up less impressive gains or even outright declines (see figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Economic success may be linked at present to vaccination success

Source: University of Oxford/Haver Analytics

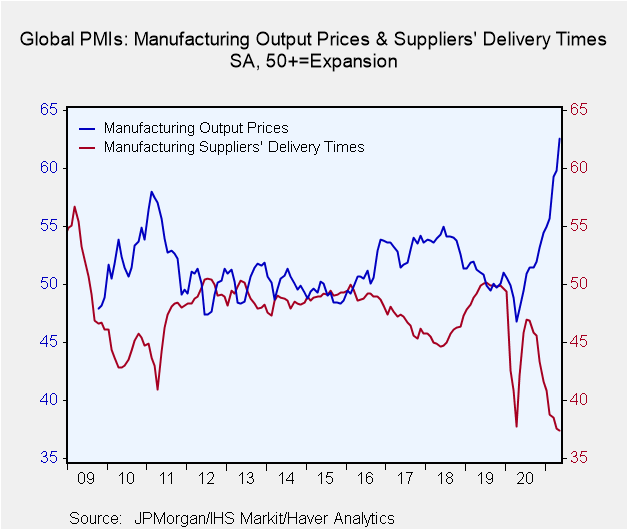

The second troubling trend relates to supply side bottlenecks and inflation. The underlying details of most countries' Purchasing Managers surveys revealed lengthening delivery times, higher numbers of order backlogs and firmer output prices (see figure 4 below). An even bigger dig into the details reveals that the rate at which delivery times worsened was much faster than the rate at which output has growing.

Figure 4: Global manufacturing PMI: Output prices versus suppliers' delivery times

The third troubling trend concerns the wheels of credit in China. For these are slowing down (see figure 5 below) probably in response to a more intense effort from the Central Bank to curtail lending growth. Excess leverage in the property sector and the heightened use of business loans to buy property in particular have concerned the PBOC and driven its policy guidance and liquidity management toward less monetary accommodation. Insofar as this has reverberations for financial conditions, capital flows and trade, this could have been a factor in driving the broader Asian region onto a slightly softer growth path in recent weeks.

Figure 5: Fading credit momentum in China

There are several implications from this analysis:

• Firstly, further positive progress on the global growth front is heavily contingent on the pace and efficacy of vaccination programmes. Policymakers in the meantime still need to be mindful of COVID mutations on the one hand and policy responses toward lockdowns on the other.

• Secondly, prospective inflation pressures are now heavily contingent on the pace at which capacity can be expanded – along with the productivity ramifications - relative to further positive progress on global growth.

• Finally, policymakers may need to be additionally mindful of any potential ramifications of a further monetary policy tightening in China, not least given its linkages with global commodity price trends and global growth and inflation outcomes more generally.

The broad policy conclusions from this seem clear. Policymakers should retain a heavy focus on the pace and efficacy of vaccination programmes with a keen eye on the global distribution. On the macroeconomic front in the meantime they should ensure companies are incentivised to make the necessary investments in labour and capital that, in turn, fosters firmer productivity growth and holds unit cost and price pressures at bay.

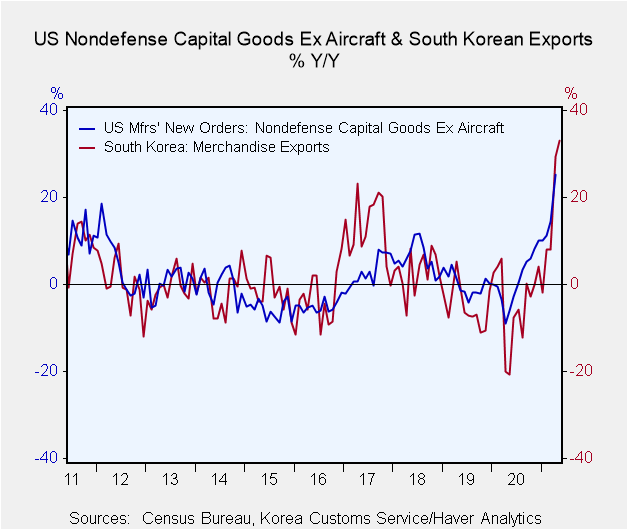

On that last point there are couple of factors that speak positively to the outlook from here. Firstly, capital spending is picking up strongly at present in a number of major economies. Annual growth rates of capital goods orders in the US and Germany, for example, are running at multi-year highs. And as we saw above, manufacturing sentiment gauges – usually a good leading indicator of capex trends – are also at multi-year highs in the US and a number of European countries. These capex positives incidentally are one reason why South Korea (and other Asian economies) have been posting double digit export growth in recent months (see figure 6 below).

Figure 6: US capital goods orders versus South Korean export growth

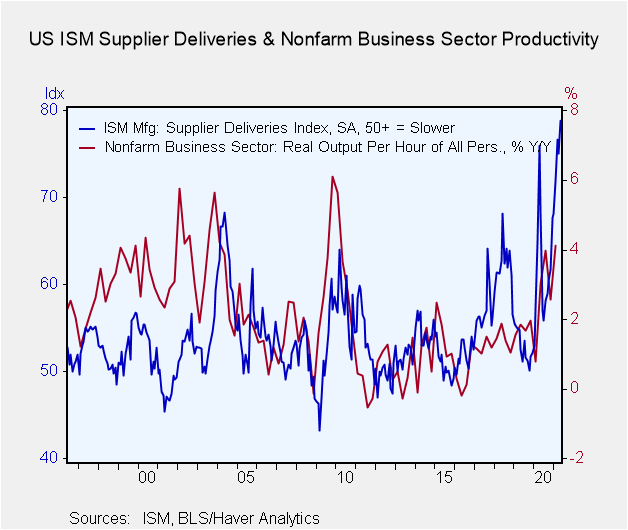

The second factor relates to the links between supply chain bottlenecks, capex and productivity growth that have held sway in the past. As figure 7 below attests, whenever manufacturers' delivery times have lengthened in earnest in the past, businesses have typically responded by adding capacity and marshalling an improvement in productivity.

There are no guarantees of these productivity echoes this time round of course not least because the pandemic is posing additional challenges. In the global recovery race, however, this is a reminder that there are several competing forces. Vaccines are competing with the virus (and mutations). And growth is competing with capacity and inflation. Navigating these crosscurrents will remain challenging and require policymakers to be both nimble and global. Straight line forecasts for, say, firmer growth and higher inflation, in the meantime, are arguably unwise.

Figure 7: US ISM: Supplier delivery times versus US productivity growth

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates