Global| Nov 21 2014

Global| Nov 21 2014Does Canada's Rising Inflation Rate Give the Central Bank Tough Choices?

Summary

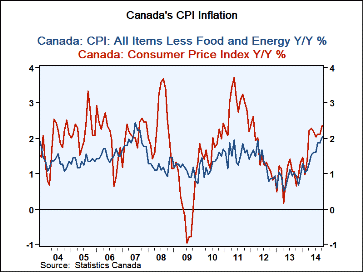

Canada's CPI inflation for October saw headline growth at 2.4% year-over-year with the ex-food and energy measure rising up to 2% year-over-year from 1.9% the month before. Costs of food and shelter advance by 2.8% year-over-year to [...]

Canada's CPI inflation for October saw headline growth at 2.4% year-over-year with the ex-food and energy measure rising up to 2% year-over-year from 1.9% the month before. Costs of food and shelter advance by 2.8% year-over-year to help boost the headline measure. Prices for natural gas, cigarette, and meat all spiked in October, helping to boost the headline, too. But technology goods and furniture prices were weak, helping to contain the overall gain. Which of these price pressures promise to have a continuing impact?

Canada's CPI inflation for October saw headline growth at 2.4% year-over-year with the ex-food and energy measure rising up to 2% year-over-year from 1.9% the month before. Costs of food and shelter advance by 2.8% year-over-year to help boost the headline measure. Prices for natural gas, cigarette, and meat all spiked in October, helping to boost the headline, too. But technology goods and furniture prices were weak, helping to contain the overall gain. Which of these price pressures promise to have a continuing impact?

First of all, the core rate, which the Bank of Canada watches most closely, is only at 2% its preferred pace. In this regard, Canada stands alone among an influential group of important central banks including the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, in successfully reaching its inflation objective. In its October report, the Bank of Canada mentioned that core inflation had risen faster than it had expected, but the pace is only up to its target and that does not make it excessive even if its pace was unexpected. The question for the BOC is "what's next?"

One view of today's data is that Canadian inflation is at target but still being pressured up. The chart in fact shows that headline inflation continues to outpace core inflation - a well-known diagnostic for continuing inflation pressures. But the headline rate of change has been flattening out. Yes, its pace is still faster than that of the core, but it has flattened out. And if we look at global inflation forces, it is hard to get too worried about the prospect that Canada might have for an inflation prospect. In fact, accelerating inflation for Canada seems a more remote prospect than drawing to an inside straight in a game of poker.

Globally, energy and commodity prices are flattening or outright falling. Canada is a country that is heavily dependent on raw material prices. If these prices are weakening, as they are, Canada is more likely to see its economy cool than to heat up. And, if that happens, the prospect for inflation to rise is dimmer. Moreover, the direct impact of weaker commodity prices will take a toll. Energy is particularly important in Canada where all sorts of avant-garde energy retrieval processes are in play including tar sands and oil shale. The recent rundown in energy prices is a further obstacle to developing these sources, although subsides may carry the day in the short run (for a while longer) there is pall cast over the longer run potential by lower energy prices and that pall will impact adversely expected growth and development.

Canada is growing, but it is not exactly posting surging growth. Its roughly 2.5% to 2.75% pace of growth is still the envy of the G-10 world. But that is hardly a galloping pace. Canadian retail sales - previously accelerating though June - are now decelerating and posting the smallest (Y/Y) growth rate since January. One concern might be that Canada's unemployment rate made a sharp move lower in October, dropping to 6.5% from 6.8% in September. Canada's unemployment started the year at 7%. Its unemployment rate was last lower in November 2008. But its labor force participation rate is lower by 0.4% year-over-year, rendering a simple view of the falling rate of unemployment simply too simple.

Just today ECB President Mario Draghi was rattling his saber about the importance of anchoring inflation expectations while asserting that in Europe they seem to be too low. In the U.S., the Fed has been watching this carefully and continues to comment on how inflation expectations are still `well anchored' even as global energy prices plunge. In Canada, inflation expectations gleaned from inflation protected securities' yields shows that over the next 10 years, inflation is only expected at a pace of 1.6%. That must be a relief to the Bank of Canada.

Clearly, the Bank of Canada has to weigh and balance a view of growing domestic tightness against a view of global laxity, global excess capacity and global disinflation. Canada, too, has to assess the impact of its demographic distortions on `measured' unemployment, the same as does the U.S. And it can do so with the knowledge that inflation expectations are still tame. On balance, the central bank may engage in some anti-inflation rhetoric with the core rate at its target and with some upward momentum still in evidence, but we think that inflation itself will prove to be a no-show in Canada as well as globally. And Canada's capital markets seem to have the same take on that. On balance, those factors will relieve the Canada's central bank from having to make any hard choices just yet.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates