Global| Oct 05 2020

Global| Oct 05 2020Emerging Markets and COVID-19

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Economy in Brief

Summary

It's always tough to generalise about emerging market (EM) economies. Even knowing if they are emerging economies can be tricky as they are classified in different ways by different organisations. China's role and relative dominance [...]

It's always tough to generalise about emerging market (EM) economies. Even knowing if they are emerging economies can be tricky as they are classified in different ways by different organisations. China's role and relative dominance in world trade and financial market flows in recent years has arguably further complicated matters not least given the underlying exposure of many smaller emerging economies to that trade and to those flows.

Rightly or wrongly, however, many observers of the global macro scene wish to understand how this aggregate grouping of EM economies are evolving, how they are coping with the COVID crisis and what their outlook might be? In this brief commentary we offer some perspective on these issues.

In summary, with the notable exception of China, the crisis is far from over for most EM economies. The underlying economic backdrop for most has been weak and a recovery in recent months has so far been fragile or elusive. While fiscal and monetary policy support have often been impressive, that has still exposed some debt-related vulnerabilities. Absent more solid foundations for income generation – and firmer export growth in particular – those vulnerabilities could weigh more heavily on the economic outlook in the period ahead.

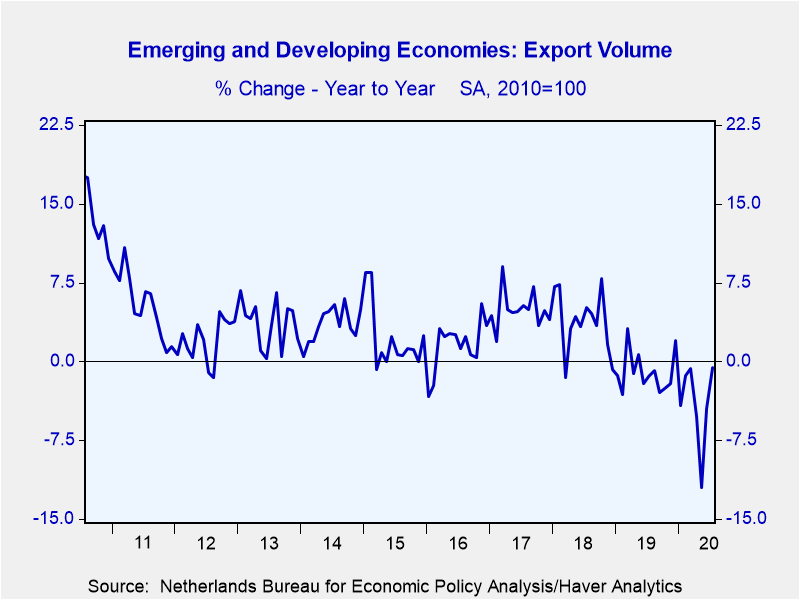

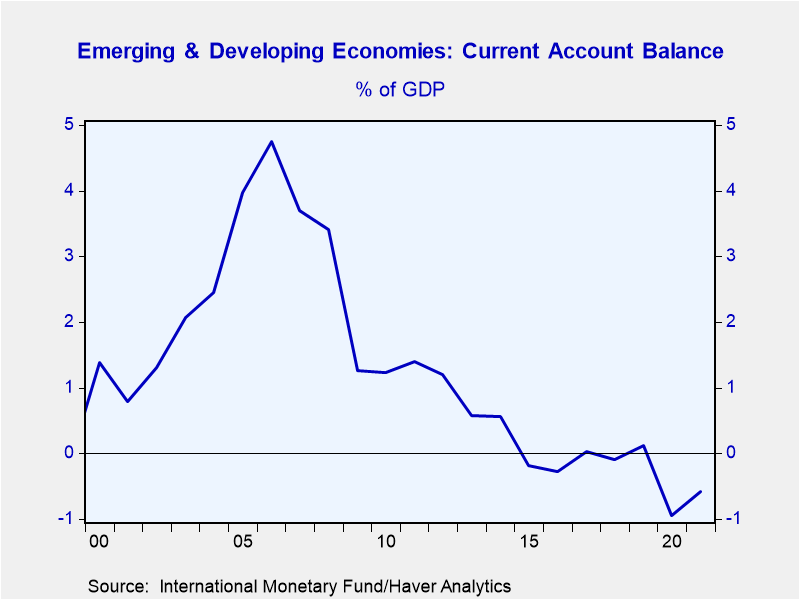

Figure 1: Structural weakness in EM trade Figure 2: EM current account balance has dipped into deficit territory

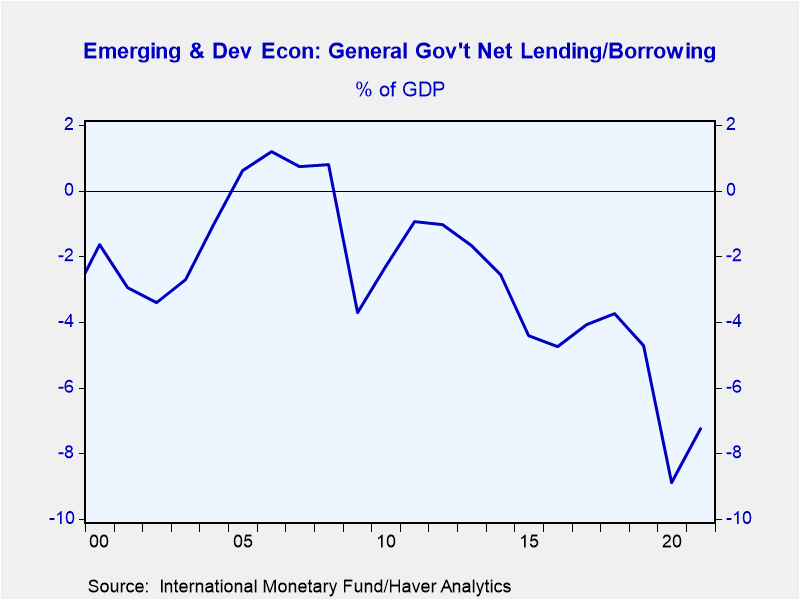

Figure 3: Weak EM growth has led to a sharp deterioration in government finances

The underlying backdrop for many emerging market economies before the current COVID crisis made a mark was weak. We explored some of the issues in a post on Asia a few weeks ago (see Asia's De-globalisation Nightmare and Covid-19) but they are worth re-stating because they apply to other emerging regions too. They concern a sharp structural erosion of export income flows and a commensurate deterioration from surplus to deficit in the aggregate current account balance (see figures 1 and 2 above). Partly because of this public finances have also been drained as economic growth has slowed. And this has meant that fiscal space has been severely depleted in recent years as well (see figure 3). Public debt ratios in the meantime have been climbing as a result.

Modest recovery from hefty Q2 contraction

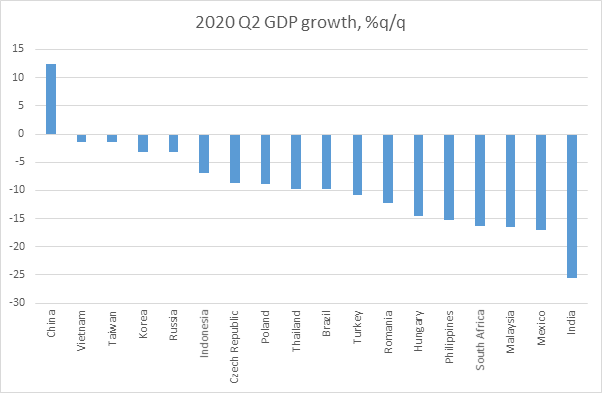

Against this rather sobering backdrop the current COVID crisis could not have come at a worse time. Indeed the impact on economic activity in many EM countries has so far been wretched. In figure 4 below we illustrate the quarterly change in GDP in Q2 for those large EM economies where the data are available. With the notable exception of China, every country on our list experienced an economic contraction and typically a very large economic contraction. China is an outlier in experiencing an advance simply because the worst of the virus and lockdown policies had unfolded in Q1 and the unwinding of these policies allowed a recovery to unfold in Q2.

Figure 4: GDP growth in Q2 collapsed in most major EM economies

Source: National sources/Haver Analytics

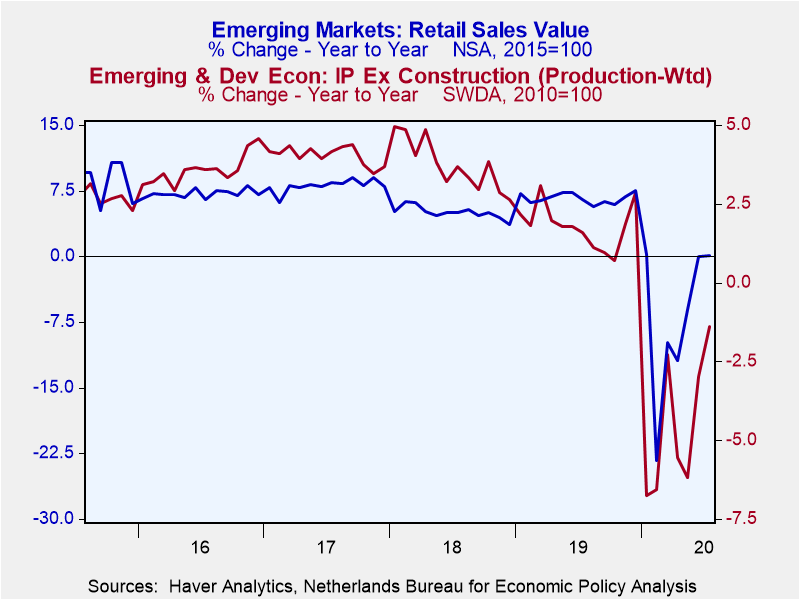

Figure 5: EM industrial production has been slow to recover

Most of these economies have recovered some poise in more recent months. But high frequency indicators such as industrial production and retail sales growth are still languishing well below pre-COVID levels (see figure 5).

Most of these economies have recovered some poise in more recent months. But high frequency indicators such as industrial production and retail sales growth are still languishing well below pre-COVID levels (see figure 5).

Testing times with COVID

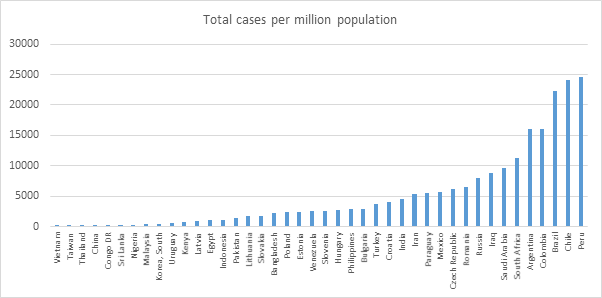

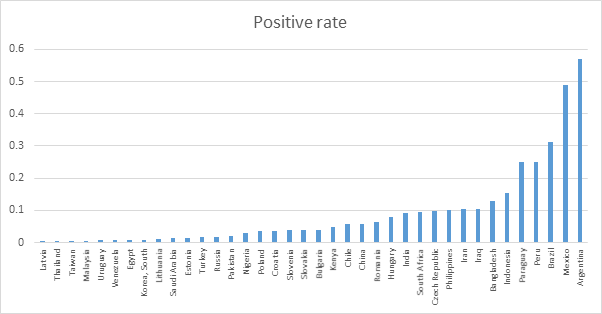

Meanwhile with one or two exceptions – and China is again one of them – the latest data that concern COVID-19 in these economies do not look that healthy either. Case numbers per million of the population are often high (and rising) as are the positive rates from current testing for some (see figures 6 and 7 below).

Figure 6: COVID-19 case numbers per million population Figure 7: The Positive Test Rate in Emerging Market Economies

Source: Oxford University/Haver Analytics Source: Oxford University/Haver Analytics

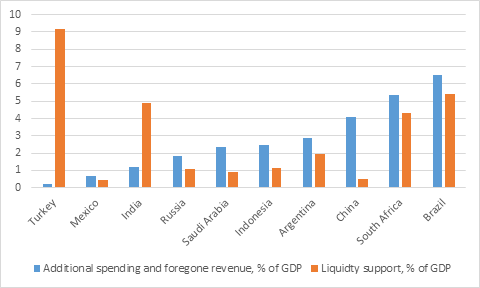

Policy response often impressive

Policymakers have responded to the crisis with a plethora of support measures with both fiscal and monetary policy playing prominent roles. Brazil, South Africa and China in particular stand out on the fiscal front. Turkey also stands out with an impressive degree of liquidity support via loans, equity injections and guarantees (see figure 8 below).

Figure 8: EM fiscal responses to COVID-19

Source: IMF/Haver Analytics

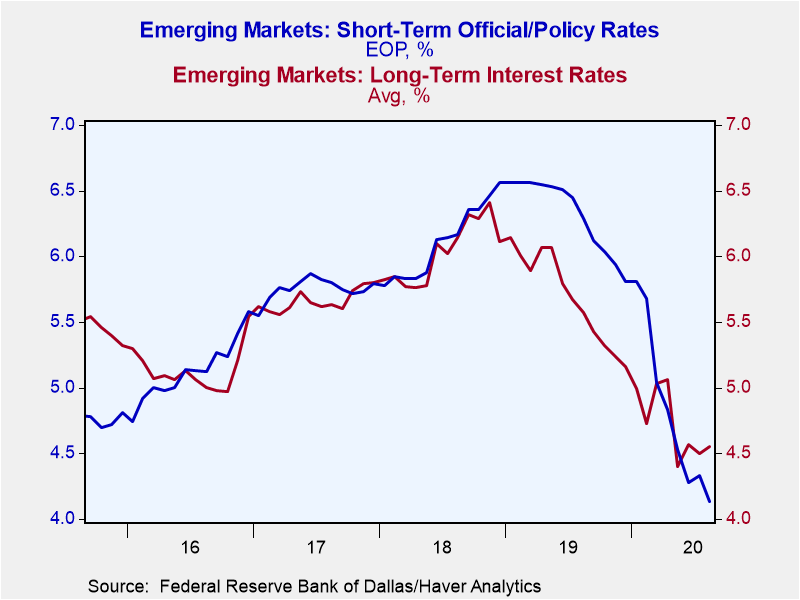

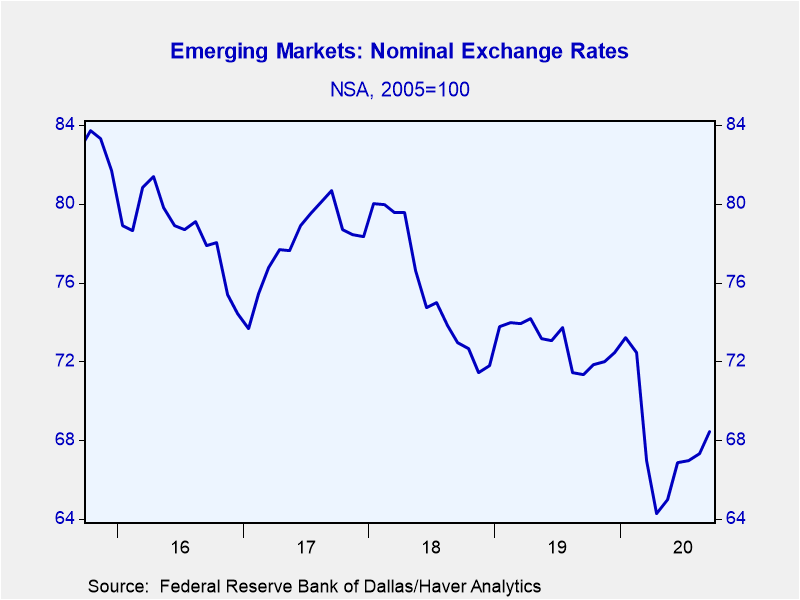

As for monetary policy, short-term interest rates have been lowered quite significantly in many countries. But thanks to large capital outflows government bond yields in many countries jumped sharply as the virus first began to circulate while exchange rates often depreciated sharply as well (see figures 9 and 10 below). And this has complicated efforts to provide policy assistance not least - as we discussed above - because there is not that much leeway to provide too much stimulus from fiscal policy.

Figure 9: Lower policy rates in EM, but higher long-term rates Figure 10: Weaker exchange rates in EM

Unconventional monetary policy in play

This has meant though that many EM central banks have turned to unconventional monetary policy in order to both fend off financial instability and shore up their economies. Specifically 16 EM central banks have announced that they are either ready to engage in government bond purchases (i.e. quantitative easing programmes - QE) or have already done so.

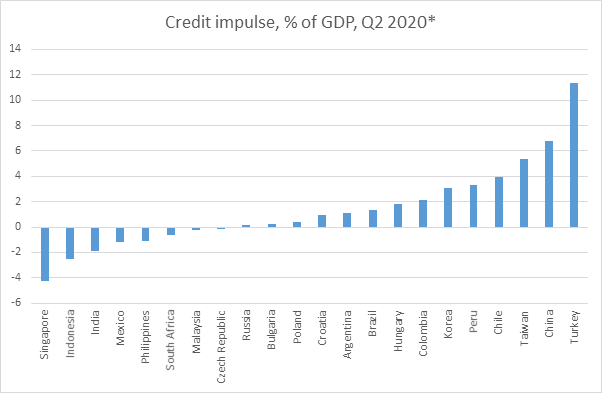

To be fair this bout of monetary easing via either conventional interest rate levers or QE (or both) appears to have met with some modest success. In figure 11 below we show the credit impulse indicators - showing the flow of new credit from the private sector - that we have recently launched (and which can be sourced from our EMERGE database) for a number of emerging market countries. Latest data for Q2 2020 suggest a stronger credit impulse has unfolded of late and particularly in China. Importantly, however, that's not a generic conclusion that one can make for all EM economies. The likes of Indonesia, South Africa and most notably India (given its relative size) faced a negative credit impulse in Q2 notwithstanding the pursuit of QE programmes.

Figure 11: Credit impulses are in positive territory in many EM economies

Source: National sources/Haver Analytics

Despite this near-term success for some EM economies, however, and for China in particular, the outlook for many EM economies remains challenging. Aside from the obvious issues that concern the virus and the healthcare policies that are required to control it, there are a number of obstacles to a trouble-free economic existence in the coming months. They concern, in part, the era of de-globalization in which the world economy now finds itself and the consequence of this, namely a lack of export income generation. The absence of that income has already allowed growth to be fuelled by more debt accumulation. And thanks to the virus and the economic policies that are being pursued to stifle its impact, further debt accumulation is inevitable in the period ahead with potential ramifications for capital flows. The sustainability of this together with its potential for generating inflation side-effects will arguably now hold the key for the economic and financial market outlook in many of these countries in the period ahead.

Viewpoint commentaries are the opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of Haver Analytics.Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.