Global| Nov 15 2013

Global| Nov 15 2013EMU Inflation Continues to Plunge-What Does It Mean?

Summary

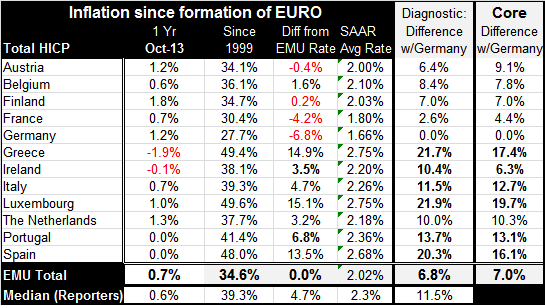

When forming the EMU, the European Central Bank pledged to keep inflation at 2%. In the better than 14 years of existence, the ECB has kept its end of the bargain holding the inflation rate to 2.02% over the period. Contrast this to [...]

When forming the EMU, the European Central Bank pledged to keep inflation at 2%. In the better than 14 years of existence, the ECB has kept its end of the bargain holding the inflation rate to 2.02% over the period.

When forming the EMU, the European Central Bank pledged to keep inflation at 2%. In the better than 14 years of existence, the ECB has kept its end of the bargain holding the inflation rate to 2.02% over the period.

Contrast this to the position of the Federal Reserve which holds that 2% is the best pace for price stability, but makes no pledge to keep inflation to any pace over any period. The ECB has engaged in price level targeting, making sure that if there was a period when inflation overshoot it was balanced by a period of undershoot to keep the price level in EMU on its long-run path.

However, even in keeping this strict and impressive pledge, all has not gone well in the eurozone. It is a lesson of how fiscal policy and monetary policy have to show balance. Each has a role to play and even if one plays its part perfectly, slippage in the other can spell disaster.

Balance is something we seem to have lost touch with on many fronts.

The United States is currently embroiled in a policy of having monetary policy make up for the deficiencies in fiscal policy. It is not clear that this can work. In the case of EMU, strict laws governing what the ECB can and cannot do have kept it from straying too far from its basic mandate.

Even so, quite part from the various fiscal woes among EMU members, inflation at the national level has not been so well controlled. The ECB was given no special tools or mandates to control inflation within the various member states. Since Germany is the largest EMU economy with the greatest weight, Germany's persistent toeing of the line helped the ECB hit to its targets over the years. When countries like Greece or Luxembourg did not hit their targets, it was not such a big deal since they are such small economies and their transgressive inflation rates would have a small impact on the overall ECB objective.

But here we are, better than 14 years after the fact, and the price level in Germany has risen by 27% over this period compared to 49% for Greece and Luxembourg. Spain's price rise has been 48%. Yet with such huge misses on the country level, the ECB has been able to claim victory over inflation. Isn't this a flaw in EMU?

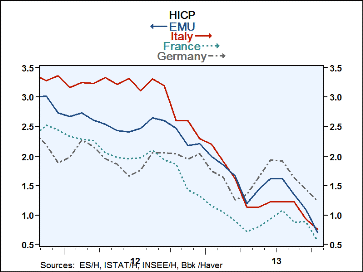

As the chart shows inflation rates in EMU as well as among its members are currently low and dropping. But the ECB is not behind on its price objective and there is no need to compress current inflation rates below 2% to keep on the ECB's long-run price path. Yet, that is what is happening.

US export and import prices today both declined along with their major components. They are both lower year-over-year too. Deflationary forces still seem to hold sway in the global economy.

Yet, the news in Europe is that Italy and Spain may have excessive budget deficits. Further fiscal squeezing is not going to stop the relentless downward pressure on prices.

China is announcing reforms today. Taking it out of its period of underperformance would also be helpful to the global economy. But it is not clear that China is advancing rules that will have enough impact.

We are left with the largest economies in the world, EMU and most of Europe, the US, Japan and China that are struggling. Indebtedness in the US and Europe has boomeranged to halt China's export machine, while Japan has struggled to escape deflation.

Growth metrics worldwide are still feeble and we see the result in prices which remain weak. While fiscal excess need to be wrung out, there has not been any consensus on how to do it without making things much worse in the short run. The ongoing problem with weak prices is evidence enough that demand has not picked up and all is not well. While there is a lot of optimism on Europe, we see the European Commission's stance on Italy and Spain and wonder how that will bring growth to Europe. We look as political log jams and the resulting fiscal contraction in the US and ask the same thing. Japan is being expansive, but it labors under a huge mountain of debt.

The age of export-led growth in the wake of no international exchange rate or balance of payments policing has been an abject failure. It accommodated the rapid rise in China, but has cut off its export ability at a crucial time. China's rapid ascent coupled with its high savings rate and undervalued exchange rate kept international macroeconomic forces from working. Instead, we were frog-marched down a dead end to our own demise. It should be obvious that demand is going to suffer when the fastest growing nations in the world that are grabbing market share and leaving the old guard with rising unemployment do not themselves consume but rather save. We used to call this the paradox of thrift. It would not have such macroeconomic impact if countries followed the balance of payments and exchange rate rules of the game. But they have not.

We see the absence of cooperation and basic lack of economic understanding in almost everything we have done over the past 30 years. Countries wanted the US to grow so they could export to it and feed off its strong domestic demand, but they wanted the US to reduce its deficits. Talk about wanting to have your cake and eat it too. Europe with its common currency area has its own internal problems it must address. Beyond that we need exchange rate and balance of payments rules the way we used to have under GATT. It's time to stop pretending that what we have is good or that it in any way resembles free trade. If lingering deflation is not a wake-up call for global policy gone wrong, I don't know what is.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates