Global| Oct 31 2014

Global| Oct 31 2014Euro Area Joblessness Hangs High as Other Activity Gauges Wither

Summary

Boo! October 31 has turned out to be a very bad data day for the European Union as well as for the euro area. It is not that one damaging report has been released, but that a series of reports shows deterioration across Europe. [...]

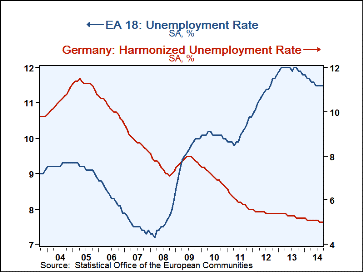

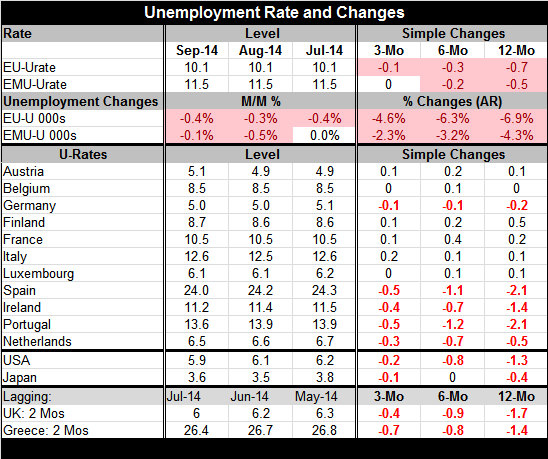

Boo! October 31 has turned out to be a very bad data day for the European Union as well as for the euro area. It is not that one damaging report has been released, but that a series of reports shows deterioration across Europe. Unemployment data, just released, show that in the EU, unemployment is stuck at 10.1%, while in the EMU area, the unemployment rate is stuck at 11.5%. Still, both areas exhibited some reduction in the numbers of unemployed in September, but not enough to move the unemployment rates. Over the last three months, among the group of 11 European Monetary Union members, unemployment has fallen in five of them. Over six months, unemployment has fallen in the same five and over 12 months, unemployment has fallen in the same five. For the rest of the countries in the table, unemployment has been generally rising. These countries are Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, and Luxembourg. France and Italy are, respectively, the second and third largest EMU members by GDP.

Boo! October 31 has turned out to be a very bad data day for the European Union as well as for the euro area. It is not that one damaging report has been released, but that a series of reports shows deterioration across Europe. Unemployment data, just released, show that in the EU, unemployment is stuck at 10.1%, while in the EMU area, the unemployment rate is stuck at 11.5%. Still, both areas exhibited some reduction in the numbers of unemployed in September, but not enough to move the unemployment rates. Over the last three months, among the group of 11 European Monetary Union members, unemployment has fallen in five of them. Over six months, unemployment has fallen in the same five and over 12 months, unemployment has fallen in the same five. For the rest of the countries in the table, unemployment has been generally rising. These countries are Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, and Luxembourg. France and Italy are, respectively, the second and third largest EMU members by GDP.

The dispersion of the unemployment rates among euro area countries continues to be extremely high, making it difficult for the European Central Bank which sets only one policy rate for all members. In addition to these facts, the EMU, however, is seeing a host of other tensions.

Only history will tell if this was a watershed day of some sort for EMU data. Yesterday saw a rise in the closely-watched EU indices. However, a series of reports today represent bad news for the euro area. The first was the unemployment report that shows joblessness stuck at a high level. The second was the flash inflation rate which shows inflation remains low as it only picked up to 0.4% year-over-year from 0.3% one month ago. Both Germany and France posted substantial drops in their retail sales. In Italy, one of the big four European economies, the unemployment rate rose. The Eurocoin indicator that tracks current growth in the euro area dropped. The UK, not a common currency member but an EU member, showed a drop in consumer confidence. These are numbers of disturbing developments among key European economies.

Separate from these trends is the decision by the Bank of Japan today to step up its program of quantitative easing. That program has rocked financial markets and sent the yen spinning lower.

Clearly, there is still a lot of weakness in the global economy. And there is reason to have concern about prospects in the euro area. At the same time, we have to admit that it's perplexing that against this background, with the U.S. economy still not on terribly firm ground, the Federal Reserve has chosen to (1) to end its program of quantitative easing, and (2) continued to be relatively upbeat about prospects for inflation getting back to 2% even after 29 straight months of missing that target.

The Federal Reserve's importance to the international economy and its decision to become less stimulative in the context of weak growth and falling oil prices and a rising dollar can only help to make everyone curious about how the Fed really thinks the `new' inflation process works. Banks in the U.S. have massive excess reserves, which they don't use because the money multiplier mechanism is no longer relevant. Central banks seem to be still-torn between the extraordinary policies that they implemented during the financial crisis and recession and their trying to decide where to go next. The ECB was late to the game of using innovative policies and that's understandable because of its charter and the reluctance of its important conservative German member.

However, the world economy is still not gaining traction. Inflation seems hardly an important risk. While a shortfall of aggregate demand is probably the most nagging problem of the global economy, we find a stricter adherence in most places to policies of fiscal conservatism than at any time in the entire postwar period.

While it is undoubtedly true that we have come to this point in history by relying too much on the creation of public debt, that doesn't mean that some expansionary fiscal policies couldn't help the economy now. It seems to me self-evident that allowing central banks to engage in such extremely excessively stimulative policies is much more risky than allowing fiscal policy a modicum of expansion. However, it's not clear that we're going to have an opportunity to test that belief.

In my view, the international trading system is responsible for many of these problems along with the excess of creation of debt. The failure of any agency or market to keep exchange rates in what economists would call equilibrium, has led to a system of disjointed and consistently out-of-kilter capital flows. This has not only facilitated the accumulation of debt that shouldn't have happened, but it has facilitated the improper allocation of resources, particularly to low-wage, low income countries, countries with an agenda to produce and not to consume. This diversion has fed the excess of production and helped to fuel the process of restricting domestic demand growth. This has fed both deflationary tendencies and weakened domestic demand growth globally. Until there is a mechanism to rebalance these imbalances, the problems we continue to fight using fiscal policy and monetary policy are doomed to failure. To solve a problem, you have to get it at its source rather than to attack its symptoms. And no one is willing to do that. We see the impact on global inflation and growth in Europe, an impact that interacts and magnifies home-grown problems and all but stifles growth. Today's data remind how far we have to go. It's a cruel Halloween trick, with no treat.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates