Global| Jun 12 2014

Global| Jun 12 2014Inflation in EMU and Differences among Members

Summary

The finalized figures in industrial production show that the European Monetary Union made a nice bounce back from previous weakness. Perhaps this will take some pressure off of the European Central Bank. However, on the inflation [...]

The finalized figures in industrial production show that the European Monetary Union made a nice bounce back from previous weakness. Perhaps this will take some pressure off of the European Central Bank. However, on the inflation front, inflation continues to be low. That is our focus here.

The finalized figures in industrial production show that the European Monetary Union made a nice bounce back from previous weakness. Perhaps this will take some pressure off of the European Central Bank. However, on the inflation front, inflation continues to be low. That is our focus here.

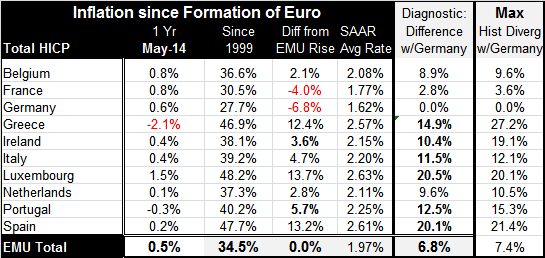

In the table below, the focus is less on the rate of inflation for the monetary union and more on the performance of individual countries. One of the big factors that is an ongoing impediment for growth in the EMU is the difference in price levels that has developed since the formation of the monetary union.

In the run-up to the monetary union, currencies were reset in a band whose purpose was to get the price levels at the right places and keep them there. Local currencies still existed, and the band's purpose was to keep the currencies close together. Even so, there was a last-minute recalibration in exchange rates before the monetary union was formed. That should have been a warning shot that all was not well among national inflation rates. But once the European monetary union was formed, the ECB only paid attention to the overall weighted average inflation rate for the EMU. That was its only charge. Since Germany has had the highest weight and has, since the EMU formation, kept its inflation rate below the benchmark 2% that the ECB aims for, there has been room for other countries to overshoot and for the ECB still to hit its target. While the ECB has hit its target, that still created a mash-up of price level differences within the monetary union. These are memorialized in the table below.

The first column shows the actual inflation rates that exist by country today. These are year-over-year rates for the original EMU members plus Greece (the group of countries is for those that have reported inflation for May). The next column shows the rise in the price level by country and for the EMU since the formation of the monetary union: after the fixing of exchange rates and ultimately the launch of the single currency. The next column shows the difference in each of these countries price level increase compared with that for the EMU as a whole. Note that only France and Germany have run inflation rates below the average of the EMU. The column to the right, entitled `SAAR average rate' shows you what inflation rate these countries have been running since the formation of the monetary union.

The final two columns are the substantial ones we want to focus on. The first is labeled `Diagnostic: Differences with Germany'. The second is labeled `Max Historic Divergence with Germany'. These titles should be self-explanatory.

The diagnostic column tells us the currently prevailing differences in the price levels since the formation of the EMU by comparing each country with the low inflation country, Germany. For example, Luxembourg has the biggest divergence, 20.5%, followed by Spain at 20.1%. After them, the divergence is not quite as sharp, only 14.9% for Greece and 12.5% for Portugal.

Despite the progress on reducing differentials with Germany, fairly sizable differences remain. The 20% difference for Spain is probably still an issue. The difference for Luxembourg probably is not since Luxembourg is principally a financial center.

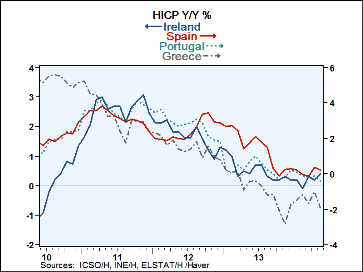

The column of the far right is very interesting when compared with the column next to it. The difference between these two rates shows us the progress that has been made in trying to eliminate the maximum price differences with Germany. For the monetary union as a whole, difference has been reduced by 0.5 percentage points. However, what's impressive is Greece. All the pain has paid off in reducing its price level divergence with Germany from 27.2% to 14.9%, a huge adjustment, in a relatively short period. Greece has managed to recapture over 12 percentage points of loss competitiveness. This is an enormous gain made by Greece, but it has been made at an enormous cost. Ireland also has made incredible progress improving its competitiveness from a 19 percentage point gap with Germany to a gap that is just over 10%. The Netherlands has made a gain of about one percentage point. Portugal has closed its gap by nearly 3 percentage points. What is clear is that the European austerity has been working and has tended to reduce price level differences among the EMU members.

Substantial differences remain, however. Spain has been making an economic recovery. Even with its 20 percentage point disadvantage with Germany. Only time will tell exactly what kind of price level differences the community is going to be able to live with. The answer is not one that's numeric but one that depends upon the actual industries in these countries and the extent to which there is direct competition with Germany and other members.

For now it looks like the EMU is making progress and faster progress that I would have thought possible. However, it still has a long way to go. One thing to bear in mind is that in many of the member countries that have undergone severe austerity, there is now less of a commitment to stay on that path. Austerity countries have seen the tremendous costs that austerity places on them and now they are more prepared for a period of growth. The danger is that they will treat austerity as a one-time fix when in fact it's an ongoing program. Substantial deviations from austerity at this point, if countries attempt to make up for lost time, could undo the progress that has been made. That, substantially, is the challenge for the euro area and ECB.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates