Global| Nov 08 2018

Global| Nov 08 2018Is the German Trade Surplus on a Sustainable Path Lower?

Summary

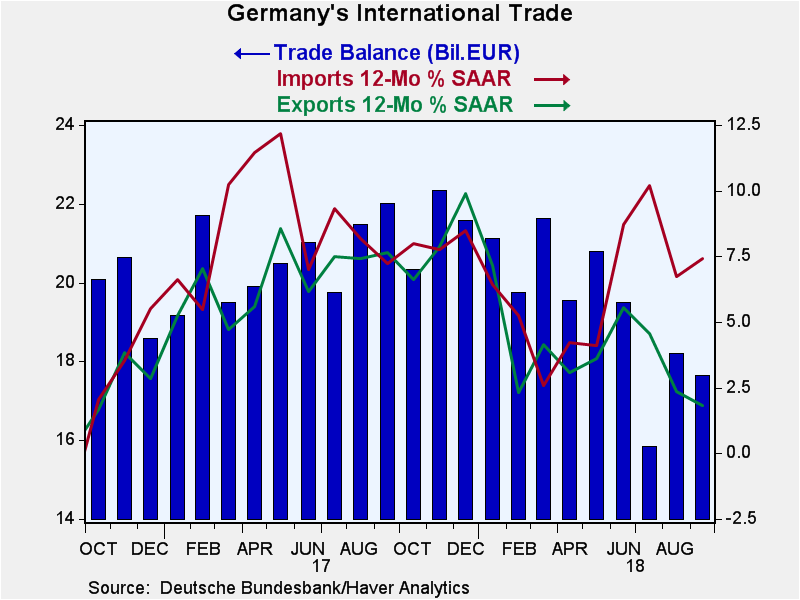

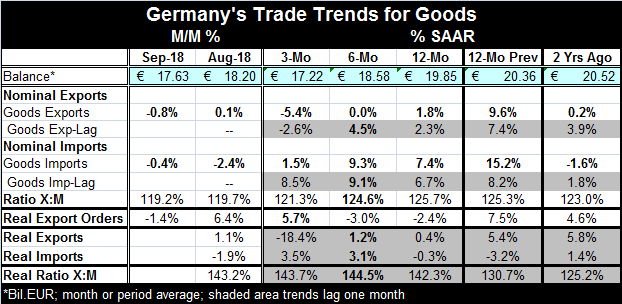

Germany's exports have lost momentum as one year ago their pace was 9.6% while now their 12-month gain is only 1.8%. Exports are decelerating over six months to a pace that is flat and they are falling at a 5.4% annualized rate over [...]

Germany's exports have lost momentum as one year ago their pace was 9.6% while now their 12-month gain is only 1.8%. Exports are decelerating over six months to a pace that is flat and they are falling at a 5.4% annualized rate over three months.

Germany's exports have lost momentum as one year ago their pace was 9.6% while now their 12-month gain is only 1.8%. Exports are decelerating over six months to a pace that is flat and they are falling at a 5.4% annualized rate over three months.

Germany continues to run surpluses overall and surpluses on its trade with EMU members; it runs a surplus on its trade with EU members who are not EMU members; it runs a surplus on its trade with non-EU members. However, in September, the EMU and non-EU member surpluses were diminished as German exports to those regions declined and as imports from each of those regions picked up. Germany's overall surplus on its trade account fell to 17.63 billion euros in September from 18.20 billion euros in August and from 22.02 billion euros in September 2017. The German surplus has started to diminish irregularly, falling month-to-month in four of the most recent six months. It has also fallen in 8 of the last 12 months. However, month-to-month changes are erratic and the statistic is devoid of magnitudes so such patterns may hide true underlying inclinations. But in this case, the German surplus does seem to be on an authentic declining path. A string of eight year-over-year deficit widening months was broken in February 2018. The year-on-year deficit then reversed its improvement to widen again in March 2018. Thereafter it continued to shrink year-over-year in five of the next six months from April to September.

The monthly pattern of declining surpluses as well as the declining profile in export growth rates make the trend to lower surpluses seem authentic. Why is this happening?

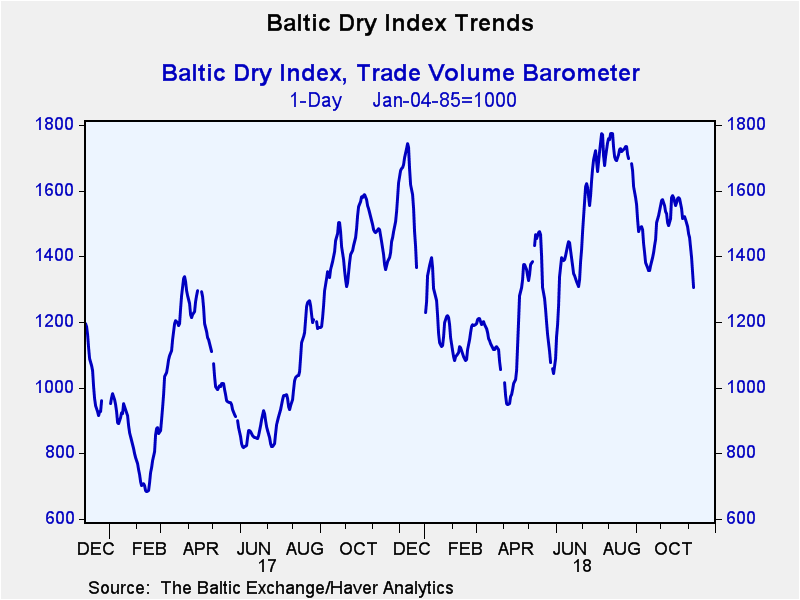

Whet your appetite to follow the Baltic Dry Goods Index

Whet your appetite to follow the Baltic Dry Goods Index

The Baltic dry goods index is suggestive as it shows global trade volumes off their peak and falling again rather sharply. Weekly data demonstrate that the Baltic index is essentially flat over 52 weeks. Daily data (Chart above) show a sharp current pullback. The Baltic index tracks international trade volume (For a quick tutorial on the index, go here)

Germany is very exposed to global trade. Its current account surplus as a ratio to GDP is over 8%; it is the highest such ratio among major trading nations. German exports of goods are 47% as large as GDP. German imports of goods are 40% as large as GDP. Clearly, Germany is going to be affected by global trade developments.

Global trade has long tended to grow faster than GDP. This is because with trade exporters can always seek out new arrangements unencumbered by domestic growth rates. It is also because most trade is in goods where productivity has been growing fastest. So when trade slows down, it affects exporting nations. The OECD area shows that trade (export and import growth) peaked early in 2018 and has been slowing ever since. Growth rates that had peaked at around 17% have slid to a pace of about 8% in about one-half a year's time. The OECD incorporates 36 countries making this a relatively broad and dependable measure of trade and trade growth trends.

Trade war!

The trade war for now includes steel and aluminum, but for other products it focuses on U.S.-China trade. It manages to create a lot of collateral damage because global supply chains are so interrelated. It is not clear how much trade wars have adversely impacted trade flows yet. U.S. exports of soybeans are sharply lower since China cut off imports from the U.S. But China's exports and imports reported today still show solid growth. It is not clear to me how long that can go on since the U.S. is simply too big a market for China for it to easily replace on any timeline let alone a short one. What is clear is that China's economy has been slowing and that Europe is in a slowdown as well. So far, the U.S. factory sector still appears to be advancing, but even in the U.S. there are sign hints of slowing growth.

Germany's oh-so special circumstances

Certainly, Germany can expect to get caught up in any trade war and expect that to create some drag on its local economy. That drag will add to the loss of momentum that will follow from Germany's choice to run a budget surplus, a fiscal policy that itself is contractionary. The Germans began to run a federal surplus in Q3 2014. Over the last 15 quarters, Germany has run 13 quarterly fiscal surpluses. Of course, this famously coincides with the period when Barak Obama and Donald Trump have asked Germany to contribute more to NATO and its own defense. Germany (instead) has prioritized the pay-down of its debt and running a fiscal surplus opting to let the U.S. fund the greater part of its national defense needs. It then called the U.S. a ‘bad ally' when the U.S. called Germany out on this slanted arrangement.

The U.S. at the center of global controversy…and would you have it any other way?

The U.S. is at the center of stimulating a lot of new world events from conflicts with its historic post-war allies over defense efforts to international trade where the U.S. has pushed for fairer trade treatment to its own view of safer nuclear arms or other arms and missile treaties (North Korea, Iran and Russia). A post- Post-War change has been long overdue. The new situation is less comfortable. But it's like buying new shores; you can't wear the old ones forever and it comes time to break in a new pair. Old Post War dependencies had to go. Germany's situation sums it up. One country cannot act to secure its future while everyone else struggles, bearing the extra cost, as the U.S. has done for German defense. The U.S. runs massive fiscal deficits and yet it protects Germany and others under the auspices of NATO and receives discriminatory treatment in return. U.S. goods have not gotten a fair treatment in Europe as European goods have gotten preferences in the U.S. These are conditions that the Trump Administration set out to realign. If we don't feed and clothe and protect everyone else, maybe we are better position to take care of our own needs?

We are about to find out where, with control of the House of Representative, the Democrats stand on these issues. Which ones do they support? Which ones will they undermine? There is already a good deal of instability in the global geopolitical system. How importantly will the new Democrat-Republican balance in the U.S. affect that? Nancy Pelosi said, “It's a new day in America.” How ‘new' will it be globally?

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates