Global| Oct 19 2017

Global| Oct 19 2017Japan's Trade Surplus Erodes Slightly As Nominal Imports Outpace Exports

Summary

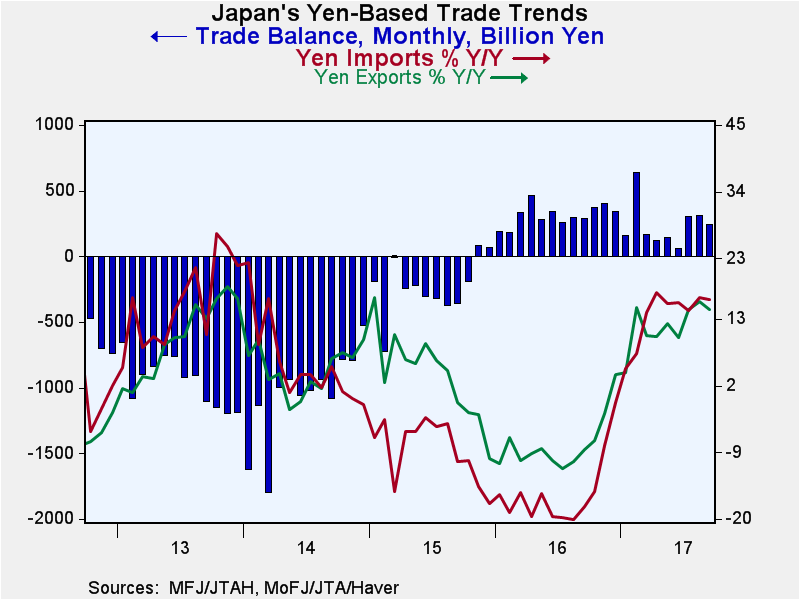

Japan ran its 24th consecutive surplus on its trade account in September. The three-month moving average of the trade balance is beginning to recover after hovering in the 300 billion yen to 359 billion yen range from mid-2016 to [...]

Japan ran its 24th consecutive surplus on its trade account in September. The three-month moving average of the trade balance is beginning to recover after hovering in the 300 billion yen to 359 billion yen range from mid-2016 to early-2017. The three-month average has climbed back up to 284 billion yen, approaching its former range. Unfortunately, the climb does not appear to be on the back of solid fundamentals.

Japan ran its 24th consecutive surplus on its trade account in September. The three-month moving average of the trade balance is beginning to recover after hovering in the 300 billion yen to 359 billion yen range from mid-2016 to early-2017. The three-month average has climbed back up to 284 billion yen, approaching its former range. Unfortunately, the climb does not appear to be on the back of solid fundamentals.

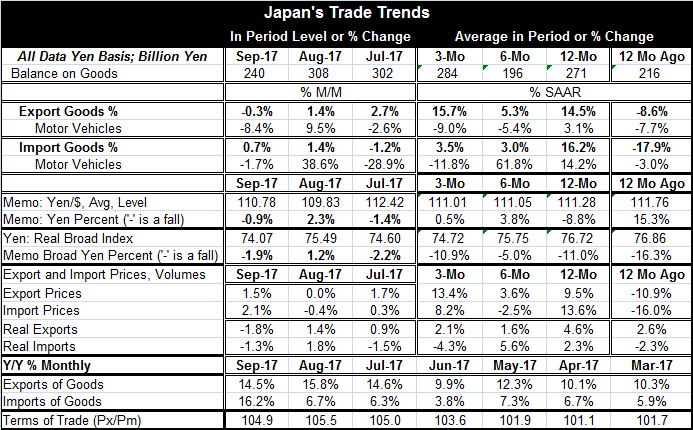

Despite the fact that the trade deficit is stabilizing, exports are still running irregular growth rates. Growth is at a 15% pace over 12 months and three months but down to 5% over six months. Imports that are up by a strong 16% over 12 months had sunk to a pace in the region of 3% to 3.5% over three months and six months.

The exchange rate vs. the dollar is not playing a big role in trade right now and the three-month, six-month and 12-month yen averages are clustered right at 111 yen. The yen measured in broad terms, however, has been slipping steadily from 12-month to six-month to three-month.

While the nominal trade values show some signs of stabilizing, there is little that is dependable going on underneath that trend. Export and import prices and trade volumes are not especially supportive. Japan's export prices are rising irregularly at a 9.5% pace over 12 months then they rise slower over six months and faster, at a 13.4% pace, over three months. Export price growth is good for the trade balance in the short run but will undermine competiveness and export value in the long run. Import prices are up at a 13.6% pace over 12 months, falling at a 2.5% pace over six months, and rising at an 8.2% pace over three months. Export and import volumes show little consistent trends, but both are decelerating. Meanwhile, imports in real terms have slowed to a crawl as exports have life with growth of about 5% in real terms.

The data suggest that Japan is not getting consistent domestic growth, to drive imports to expand. Meanwhile, exports are up at a somewhat better 5% rate of growth that suggests some growth in demand externally. Still, at 5% export growth, external demand is not terribly strong and the rate represents an ongoing slowdown, not a speed up.

While global PMIs have showed some pick up, their advance has leveled out. The strength that remains is in the more industrialized economies, while emerging economies are still a step behind the recovery process. Japan's most important trading partner is China and China's manufacturing PMI gauge has been hovering about the 51 mark which is only slightly above the breakeven value of 50 for a diffusion index. And for China, a reading in the PMI range of 51 is among the strongest readings it has been able to post since January 2012.

There is a good deal of anticipation in markets. In the U.S., the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed above 23,000 for the first time on Wednesday. Even market bulls are a bit wary of the lofty levels it has achieved on such uneven fundamentals. The Fed's Beige Book for this month was just released and if the Fed had used the words 'moderate' and 'modest' any more in the report to describe the economy it would have been fined by the language police. Despite rising bond yields and stock prices and despite a Fed plan to tighten, activity is not really accelerating. The U.K., as Mark Carney pointed out this week, is caught in some difficult cross currents. ECB members are gradually, cautiously, declaring their preparedness for less stimulus. And as the U.S. stock market soars, the Fed is dismantling its bloated balance sheet slowly and is moving somewhat unsteadily toward a the rate hike in December. Yet, the Fed's own Beige Book, a compilation of anecdotal data from its business contacts across the country, continues to show a tighter labor market that produces none of the trappings of a tighter labor market. That means that the Fed's conundrum is fully in place. And despite the fact that the economy is acting as the Fed expects, and that it is not generating the inflation that the Fed expected, inflation was used as a justification for its first rate hike one and three quarters years ago. And despite not hitting that mark, the Fed is showing little hesitation to keep up the rate hikes. And that will matter, too.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.