Global| Dec 28 2016

Global| Dec 28 2016Surprise Confidence Rise in Troubled Italy

Summary

Italian consumer confidence jumped to an index reading of 111.1 in December from 108.1 in November. The confidence index which had peaked in this cycle in November 2015 had been in a steady slide and had fallen or been flat in seven [...]

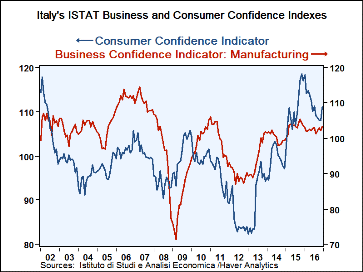

Italian consumer confidence jumped to an index reading of 111.1 in December from 108.1 in November. The confidence index which had peaked in this cycle in November 2015 had been in a steady slide and had fallen or been flat in seven of the previous eight months. Yet, it made a very surprising and sharp turnaround in December, logging its largest one-month gain in nine months. The reversal has come in the midst of political turmoil with a new government being formed as Italians had gone to the polls to reject a referendum proposed by the previous prime minister who resigned in the wake of this referendum's defeat. Italy, also struggling under banking sector problems, has continued to display signs of economic malaise. Nonetheless, out of the blue, Italian consumer and business moods are on the rise in December in a display of exogenous happiness.

Italian consumer confidence jumped to an index reading of 111.1 in December from 108.1 in November. The confidence index which had peaked in this cycle in November 2015 had been in a steady slide and had fallen or been flat in seven of the previous eight months. Yet, it made a very surprising and sharp turnaround in December, logging its largest one-month gain in nine months. The reversal has come in the midst of political turmoil with a new government being formed as Italians had gone to the polls to reject a referendum proposed by the previous prime minister who resigned in the wake of this referendum's defeat. Italy, also struggling under banking sector problems, has continued to display signs of economic malaise. Nonetheless, out of the blue, Italian consumer and business moods are on the rise in December in a display of exogenous happiness.

Monthly changes

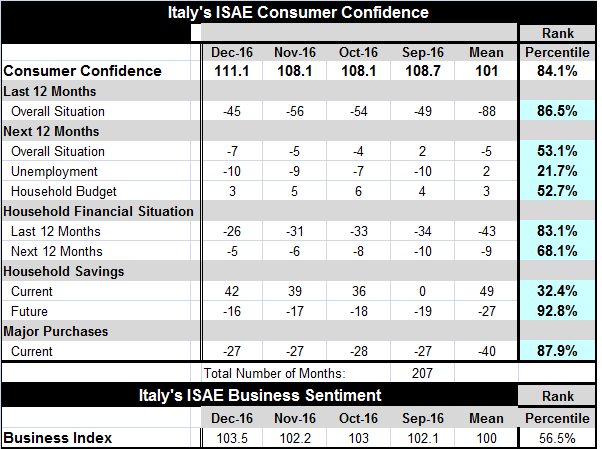

The prospect of unemployment is highly correlated with the overall confidence measure in Italy. Unemployment prospects were slightly reduced in December. However, the overall situation was assessed as worse and household budgets were rated in worse shape than in November. However, Italy is coming off a month in which it is rating the past 12-months relatively highly; the best since March of this year. Of course, that is backward looking and it is for a period in which the current confidence measure has been steadily eroding.

Households do assess their past financial situation as having improved and project some small further improvement over the next 12-months. Households' ability to save continues to improve and prospects for improvement ahead also crept marginally higher. The conditions for making a major purchase are unchanged in December from November.

Levels of contentedness

In terms of the assessments of the levels of these various variables, overall confidence has an 84th percentile standing- better only 16% of the time. The overall situation over the past 12-months has been better less than 14% of the time and over the next 12-months the expectation for the overall situation has a 53rd percentile standing, a reading that is just a bit above its median (which occurs at a queue standing of 50). Also for 12-months ahead, unemployment proses are lower only 21% of the time, a relatively good low reading. The household budget is in better share less than 48% of the time, another near-median response.

The household financial situation for the past 12-months is assessed as having been better only about 17% of the time while the view ahead at a 68th percentile standing is less robust but still positive. Household savings currently are given only a below median 32nd percentile standing; but for the future the reading edges only slightly higher in December but reaches a standing in its 92nd percentile, rarely stronger. The environment to make a 'major purchase' has been locked in a tight race for several months and currently has a robust 87th percentile standing.

Business confidence is up too

Italian businesses saw a jump in this assessment in December as well and their current condition is assessed modestly above its median at its 56th percentile.

An elusive rational for improvement

Italy's confidence level is hard to describe and understand. The levels of confidence show some disconnect with relative economic performance. Among the original EMU members, Italy has had the weakest year-over-year growth as of Q3 2016. In Q3 itself, Italy's quarterly growth rate is tied for the fourth weakest among this group of 11 countries (including Greece). Since the EMU was formed, Italy has had the weakest GDP rise among the three largest EMU economies with a cumulative GDP rise of only 17.6% while Germany and France have seen real GDP by 49.2% and 47.1%, respectively. Austerity that has been imposed because of excessive Italian budget deficits and inflation have really pulled Italy back and led to resentment and to a growing anti-European and anti-euro mood. Before the financial crisis, Italy still had been lagging. Its GDP at that point had grown only about 63% as fast as Germany's and France's since the EMU formation. But by Q3 2016, that proportion has slipped to only about 36% to 37% of their cumulative growth. Italy is being left behind. Meanwhile, the U.K. (a country that has been operating in the EU but not as a part of the single monetary unit -not in the EMU) has grown by 67% since the EMU was formed. That is a 36% premium to Germany and France. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that, whatever the benefits of EMU membership, they are not growth maximization. There is a natural bias to keep growth rates near those of Germany, a country that prizes steady and moderate rates of growth, to keep inflation, fiscal and trade accounts in balance. Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece are examples of what happens if those accounts are allowed to stray. Meanwhile, Germany continues to run the most consolidated fiscal program in the euro area and runs massive trade and current account surpluses even though that is not supposed to be allowed. To be sure, there is a lot of disequilibrium being fostered by the EMU. Without the same sort of fiscal sharing scheme as among states in the U.S., these sorts of differences tend to breed political pressures.

What is interesting for Italy is that despite the economic underperformance and the stress and despite a surging political opposition that seeks restoration of the lira among other goals, the Italian majority continues to like the EMU and wants to keep the euro. Italy continues to labor under poor economic terms. Its political situation is very much in flux. Its institutional framework, especially regarding how its banks will fare in the wake of the massive needs by Monte Dei Paschi alone, is in need of a fix. Italy faces ongoing challenges that will put its new-found bump up in confidence to the test.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.