Global| Mar 20 2025

Global| Mar 20 2025Charts of the Week: Reversal of Fortunes

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Economy in Brief

Summary

US equity markets have underperformed relative to global peers in recent weeks, as investor sentiment has deteriorated in response to weaker-than-expected growth data and growing concerns about the Trump administration’s economic policies (chart 1). The administration’s renewed push for tariffs, alongside fiscal expansion and tighter immigration policies, has fuelled stagflation fears, compounding the uncertainty surrounding the Fed’s next steps. This week, the Fed opted to keep its policy rate on hold but acknowledged rising downside risks by revising its GDP growth forecast lower, signalling caution about the economic outlook despite lingering inflation concerns. Foreign capital flows into US assets and their impact on the strong dollar are also showing signs of softening, as trade tensions and policy unpredictability raise questions about long-term US economic stability (chart 2). Meanwhile, global imbalances remain entrenched—China and Germany continue to run high savings rates, while the US remains structurally dependent on external capital to finance its deficits (chart 3). Trump’s efforts to rebalance trade through protectionist measures may struggle to overcome these deeper economic realities, particularly as demographic trends reinforce the service-oriented nature of the US economy and constrain China’s transition to a consumption-driven model (chart 4). Other central banks are also caught in this evolving landscape—wage growth is slowing in Europe, but lingering inflation risks suggest that rate-cutting cycles could remain uneven (chart 5). For China, where the property market downturn has been a major drag on growth, recent policy measures have offered signs of stabilization, but the road to recovery also remains uncertain (chart 6). With the US economy at risk of slowing more sharply than anticipated, central bank policies finely balanced, and China’s long-term growth trajectory still in question, the coming months could prove pivotal in determining whether global financial markets find their footing or remain mired in volatility.

US equity markets Chart 1 below highlights how the US equity market has historically responded well to positive economic surprises but faltered when growth data disappointed, a trend that has resurfaced in early 2025. Investor concerns have intensified as the Trump administration's policies have raised fears of supply-side constraints and stagflation. The latest downturn in growth surprises suggests the US is losing momentum faster than anticipated, fuelling recession speculation just as policy uncertainty and still-tight monetary conditions weigh on corporate earnings.

Chart 1: Global equity markets have been responding to heightened US recession concerns

US capital flows Against this backdrop, the US dollar and foreign demand for US financial assets are also in focus. Chart 2 shows a clear (albeit, loose) relationship between movements in Haver’s calculation for the broad nominal effective US exchange rate and net private sales of U.S. domestic securities—with periods of dollar strength coinciding with increased foreign purchases of US assets. However, recent volatility suggests that global investors may be reassessing their appetite for US securities. A stronger dollar, often a symptom of risk aversion, has historically attracted capital inflows, but persistent trade frictions could lead to capital flight if investors begin to question the long-term implications for US economic stability.

Chart 2: Haver’s calculations for the US trade weighted exchange rate versus US capital flows

Global re-balancing The trends in chart 3 below highlight one of the fundamental tensions in the global economy: the persistent gap in savings rates between China, Germany, and the United States, which is one reason (alongside relative investment proclivities) for trade and capital flow imbalances. China’s exceptionally high savings rate—consistently above 40% of GDP—reflects its export-driven growth model, where low domestic consumption rates and state-led investment create large external surpluses. Similarly, Germany’s high savings rate, hovering around 30% of GDP, stems from policies that have arguably compressed domestic wages and reinforced a structural reliance on exports. In contrast, the US has maintained a much lower savings rate, historically around 15-20%, reflecting its dependence on domestic consumption and foreign capital inflows to sustain investment. This imbalance has long made the U.S. the "consumer of last resort," absorbing excess savings from surplus economies, a dynamic that President Trump has repeatedly attacked as unfair.

Chart 3: National Savings Rates in the US, China and Germany

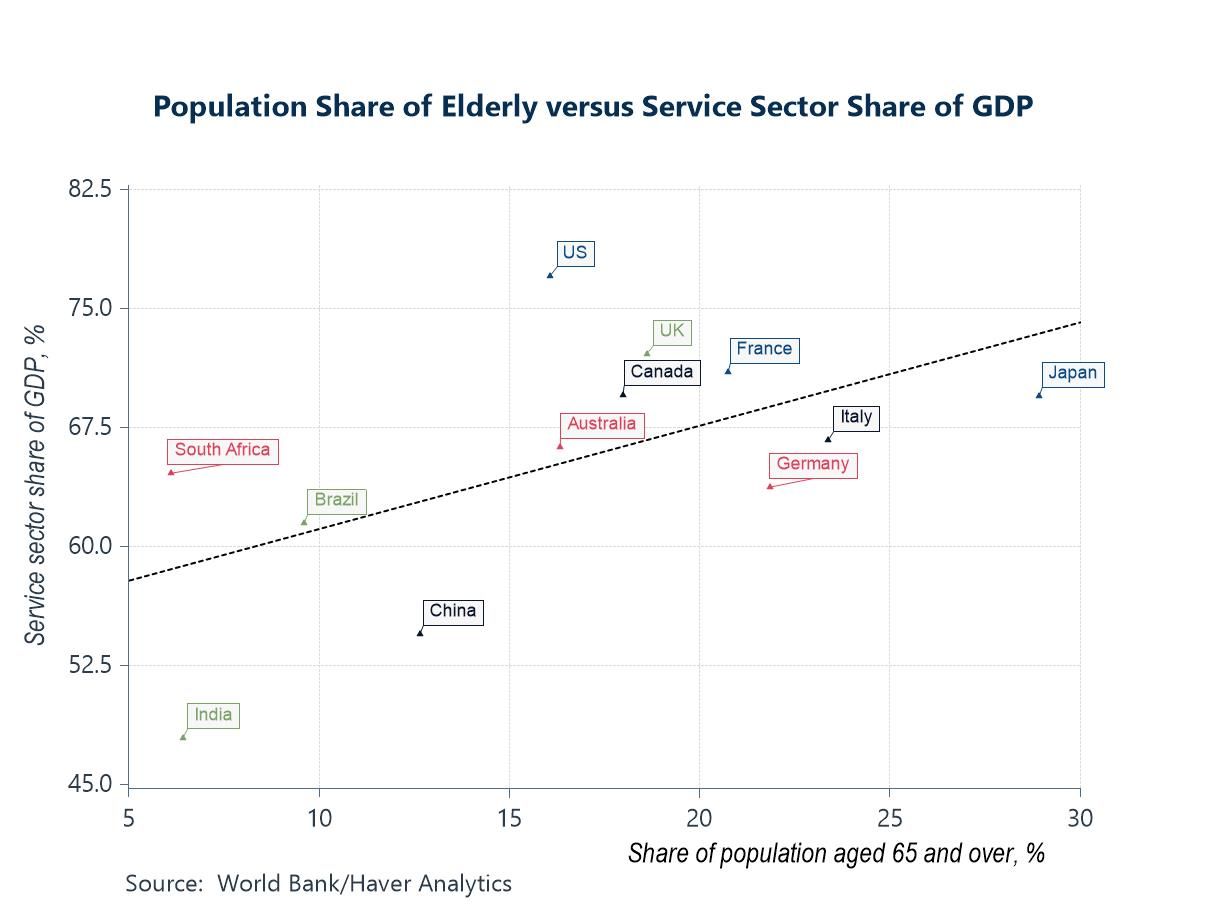

Ageing and services Tariffs alone may not achieve the US administration’s goals, as they fail to address deeper structural drivers of global trade imbalances. While tariffs make imports more expensive, they do little to alter economic specialization shaped by demographics and domestic structures. The US has a disproportionately large service sector due to its consumption-driven economy, high healthcare spending, and dominant financial services, while China’s remains underdeveloped despite an ageing population, reflecting its investment-heavy model and weaker safety nets (chart 4). This divergence fuels trade imbalances, with the US absorbing demand from surplus economies like China, which prioritizes manufacturing over services. Efforts to rebalance trade through reshoring face resistance from these entrenched models—China’s shift toward a consumption-led economy will take decades, while the US remains dependent on foreign capital. Until these imbalances adjust, trade tensions will persist, with policy struggling to override structural economic forces.

Chart 4: Elderly population shares are linked with an economy’s service sector share of GDP

Wage inflation in the US and Europe According to the latest trackers from the Indeed hiring company wage growth is slowing across major economies, but differences between the US, UK, and Eurozone highlight lingering challenges for central banks and particularly the Bank of England. US wage growth, which peaked at nearly 9% in 2022 amid labour shortages and policy stimulus, has fallen to just around 3%. The Eurozone has followed a similar trend. In contrast, UK wage growth remains close to 6%, thanks to worker shortages, cost-of-living adjustments, and possibly some Brexit frictions, which are posing a greater inflation risk (chart 5).

Chart 5: The Indeed hiring company’s latest trackers suggest slowing wage growth in Europe

China’s property market China’s property market is showing early signs of stabilization, with the Real Estate Climate Index beginning to recover and the pace of house price declines slowing. The price index for existing residential buildings across 70 cities, which had been in steady decline since 2021, is now deflating at a much slower rate, suggesting that policy support is gaining traction. The Real Estate Climate Index has also begun to edge higher, indicating a tentative improvement in market sentiment (chart 6). This turnaround follows a series of government interventions, including interest rate cuts, relaxed mortgage rules, and targeted support for developers. While challenges remain, particularly in restoring broader homebuyer confidence and sustaining demand, the latest data suggest that the worst of the downturn could be over. Whether this recovery can gain momentum will depend on the effectiveness of continued policy easing and whether China’s broader economic environment supports a sustained rebound in real estate investment.

Chart 6: Signs of a bottoming in China’s property market

Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates