Global| Jan 23 2025

Global| Jan 23 2025Charts of the Week: Trump Cards

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Economy in Brief

Summary

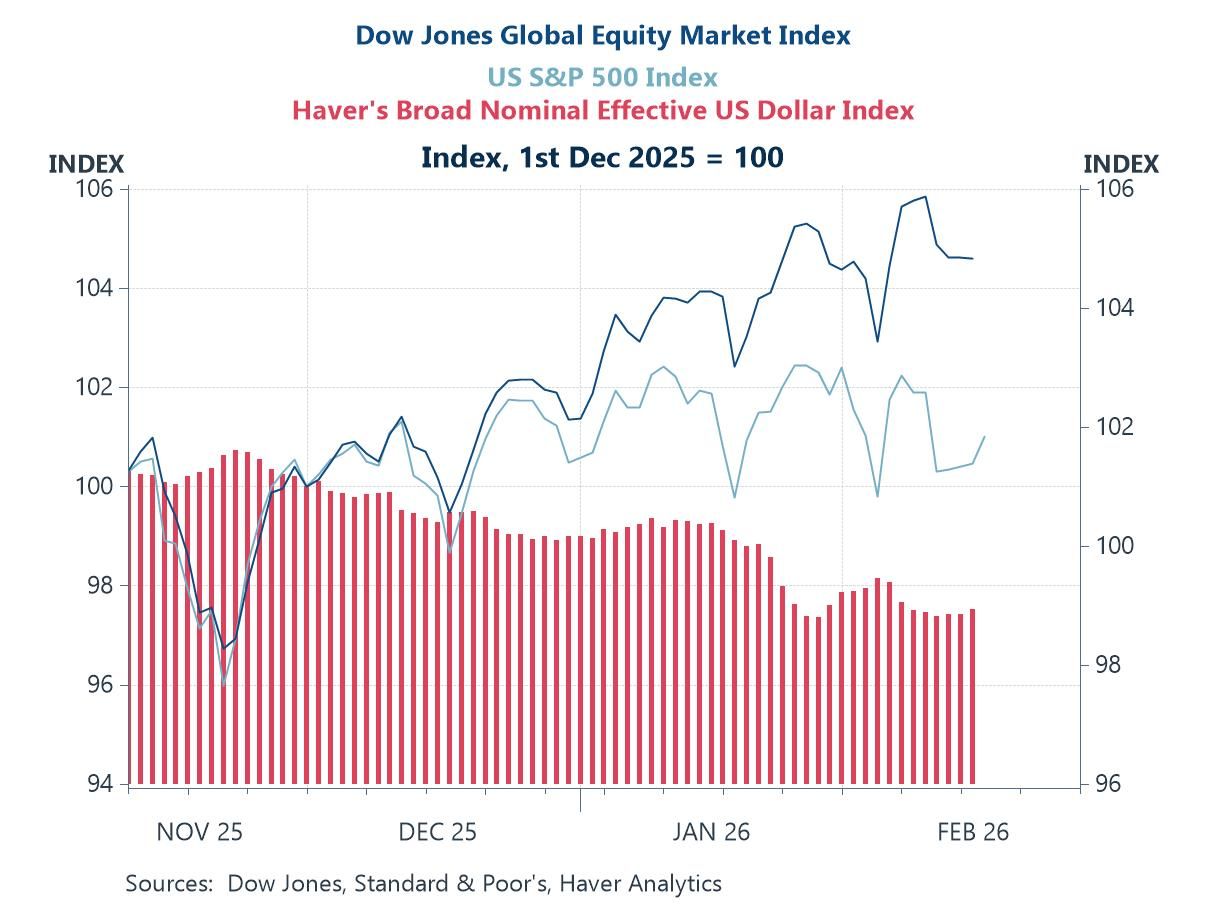

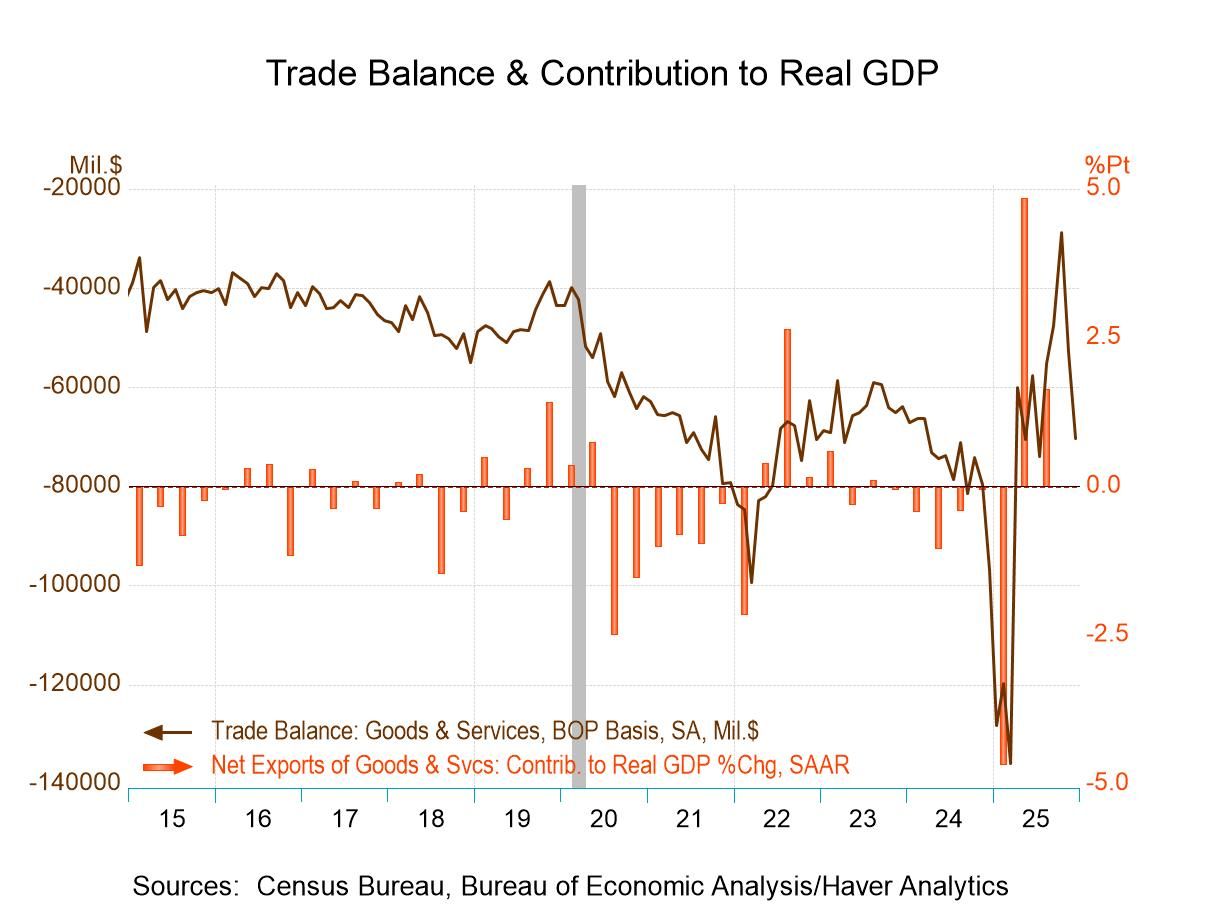

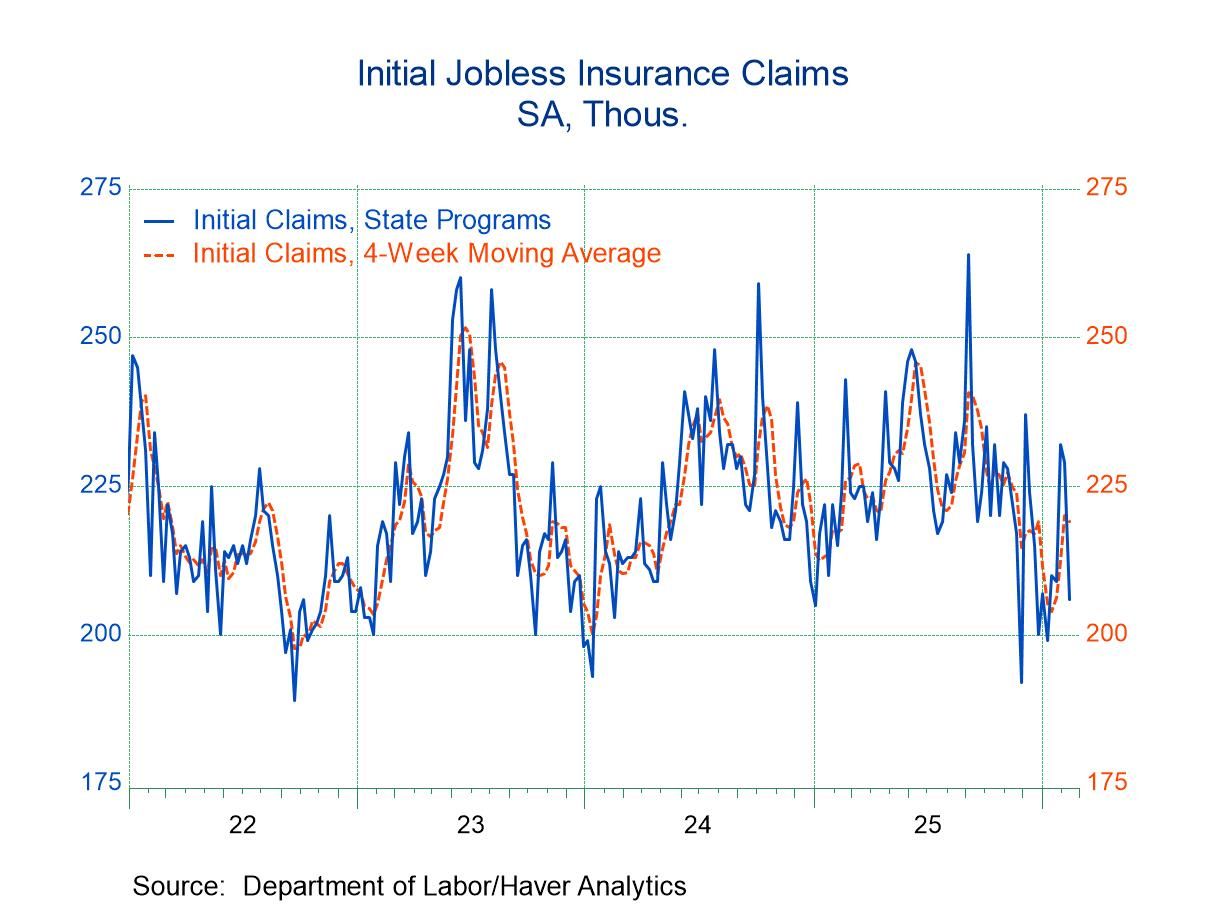

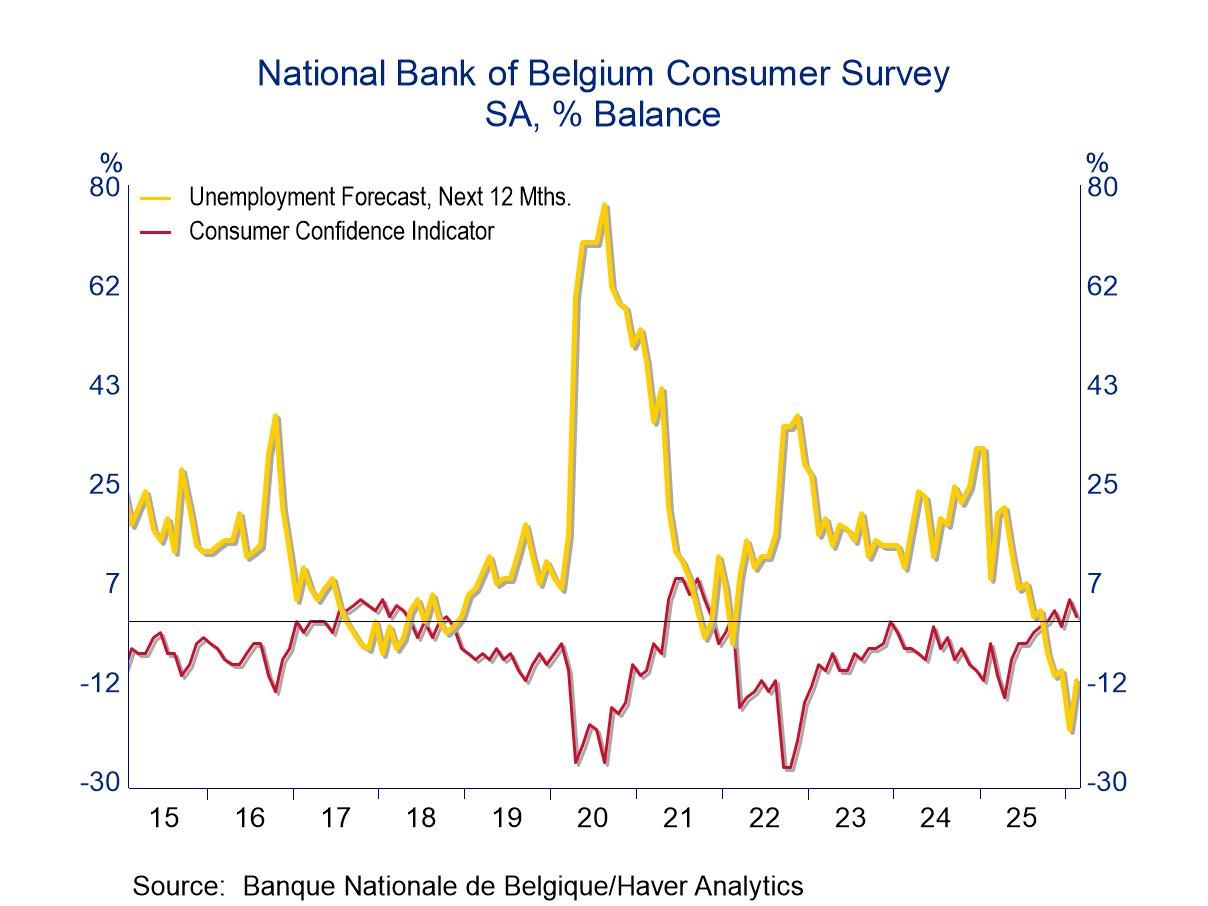

Financial markets have enjoyed a notable lift in sentiment over recent days, driven by renewed optimism about the domestic economic policies of a new US administration. Investors have certainly been cheered by early signals of a pro-growth strategy, with the energy sector taking centre stage following a ceasefire between Israel and Gaza and the announcement of measures aimed at reducing US energy costs (see charts 1 and 2). Meanwhile, China’s stronger-than-expected growth figures last week and softer-than-expected inflation readings from both the US and the UK have fuelled gains across equity and bond markets, bolstering risk appetite in other markets. However, despite the prevailing optimism, several factors warrant caution. Chief among them is the global uncertainty that surrounds the policy choices of a new US administration. The policy choices of central banks will also be critical, particularly as labour market strength could keep inflation risks alive (charts 3 and 4). Questions also linger about China’s ability to sustain its growth momentum, especially as its property sector and consumer demand face ongoing challenges (chart 5). Finally, while artificial intelligence is increasingly seen as a driver of future growth and productivity, doubts persist over its near-term potential to meaningfully transform the world economy (chart 6). For now, investors appear content to ride the wave of positive sentiment, but vigilance over these risks will be critical as the economic landscape continues to evolve.

Energy and labour markets Chart 1 below highlights two key trends: the real consumer price of energy in the OECD economies (indexed to 1970) has shown significant volatility, with sharp spikes during periods of energy crises (e.g., 1970s oil shocks, 2008, and post-pandemic supply constraints) and declines following market adjustments or advances in energy production. Meanwhile, the US labour share of business output has experienced a steady decline since the 1980s, reflecting structural changes in the economy such as globalization, technological advances, a shift in bargaining power away from labour toward capital as well as higher real energy prices. These trends and the interplay between them will arguably form the basis of several policy choices that will be made (or already are being made) by a new US administration.

Chart 1: The real consumer price of energy in the OECD versus the US labour share

Electricity prices Energy prices, their level and their volatility, arguably play a much bigger role in broader macroeconomic fluctuations than they are given credit for. Chart 2 below shows electricity prices (a 2-year average) across six major developed economies. It shows that the US has faced the cheapest electricity at around $44/MWh. The UK and Germany, in contrast, have faced the most expensive electricity at respectively $106/MWh and $94/MWh. This disparity reflects a mix of factors: European countries, particularly the UK and Germany, face elevated prices due to heavy reliance on natural gas imports, exacerbated by geopolitical tensions (e.g., reduced Russian supply), higher renewable energy integration costs, and carbon pricing mechanisms. The US, in contrast, enjoys lower electricity costs due to more abundant domestic energy resources, particularly natural gas, and less exposure to international energy markets. Against this backdrop it is hardly a surprise that the US economy has flourished (relative to other advanced economies) while the UK and Germany have floundered.

Chart 2: Electricity prices in selected major economies

The UK labour market This week’s labour market data additionally suggest that the UK will probably struggle to keep pace with the US economy in the period immediately ahead. The data specifically revealed that employment growth is slowing on all measures, and the PAYE measure of payrolls in particular (see chart 3 below). And while private sector pay growth has also slowed, the 6-month annualised rates of growth still stood at a relatively lofty 5.8% in December. Weaker employment growth will encourage the BoE to cut rates again before too long (probably in February) but weaker wage growth could also be necessary for a much looser policy stance to be enacted over the next few months.

Chart 3: The UK labour market: employment and earnings growth

Household savings and labour market activity At a broader global level, a key risk to the economic outlook at present concerns restrictive monetary policy and its impact on labour market activity and household spending. Chart 4 below shows that household saving rates in the world’s major economies have – on the whole – been rebounding over the past two years. Simultaneously, the unemployment rate in advanced economies has begun to climb. These trends align with the tightening of monetary policy that’s been enacted in recent years and economic uncertainty. But if that combination persists, it could place a bigger brake on the world economy this year than many analysts are anticipating.

Chart 4: The household savings rate versus the unemployment rate in advanced economies

China’s credit impulse Another big source of uncertainty, at present, concerns China. Chart 5 below compares the Citigroup Economic Surprise Index for emerging markets (EM) and Haver’s calculations for China’s credit impulse (the change in new credit as a percentage of GDP). The chart suggests that China's credit growth influences broader EM economic fluctuations. During periods of robust credit growth (e.g., 2020-2021), driven by stimulus measures, EM economies benefited from improved liquidity and demand from China. Conversely, periods of credit tightening (e.g., 2017 and 2023-2024) weighed on economic surprises, reflecting weaker support for growth. These dynamics underline China’s outsized role in shaping sentiment and economic conditions in emerging markets. That its credit impulse, moreover, remained negative in Q4 (of 2024) underscores how China might continue to exert downward pressure on the world economy in the period immediately ahead.

Chart 5: China’s credit impulse versus emerging market growth surprises

South Korean trade Another source of uncertainty for the world economy, at present, is the optimism surrounding AI. While proponents highlight its transformative potential to boost productivity, efficiency, and innovation across industries, sceptics question the timeline for a meaningful economic impact. With that in mind it would be inappropriate to draw strong conclusions from chart 6 below but it is certainly of note that South Korea – which has been heavily reliant on AI-fuelled trade – saw a big slowdown in export growth in the first 20 days of January. Much of that slowdown, moreover, could be traced to a big drop in semiconductor trade.

Chart 6: South Korea’s export growth in the first 20 days of the month

Andrew Cates

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Andy Cates joined Haver Analytics as a Senior Economist in 2020. Andy has more than 25 years of experience forecasting the global economic outlook and in assessing the implications for policy settings and financial markets. He has held various senior positions in London in a number of Investment Banks including as Head of Developed Markets Economics at Nomura and as Chief Eurozone Economist at RBS. These followed a spell of 21 years as Senior International Economist at UBS, 5 of which were spent in Singapore. Prior to his time in financial services Andy was a UK economist at HM Treasury in London holding positions in the domestic forecasting and macroeconomic modelling units. He has a BA in Economics from the University of York and an MSc in Economics and Econometrics from the University of Southampton.