Asia| Nov 13 2023

Asia| Nov 13 2023Economic Letter from Asia: Examining Indonesia

We move our attention this week to Indonesia, in light of its Q3 GDP readings released last week. The resource-rich economy is the largest in Southeast Asia and the fifth-largest in Asia by GDP, providing the bulk of the world’s nickel and palm oil supplies. Indonesia is also an important producer of other base metal and agricultural products including tin and natural rubber, and of energy commodities like coal. While slightly weaker, Indonesia’s Q3 GDP growth hovered near pre-pandemic rates, with private consumption once again the main growth driver. Delving deeper, we note continued weakness in Indonesia’s exports, which have been weighed by soft export prices despite relatively steady demand volumes. We then turn to examine Indonesia’s position as a minerals producer and its efforts – including outright export bans – to ascend the global minerals value chain. We next take stock of recent developments with the Indonesian rupiah and its relative resilience against the US dollar, noting stabilization support from the central bank. Lastly, we dive into the bank’s newly minted monetary policy tool aimed at attracting foreign inflows and discuss preliminary market responses and results.

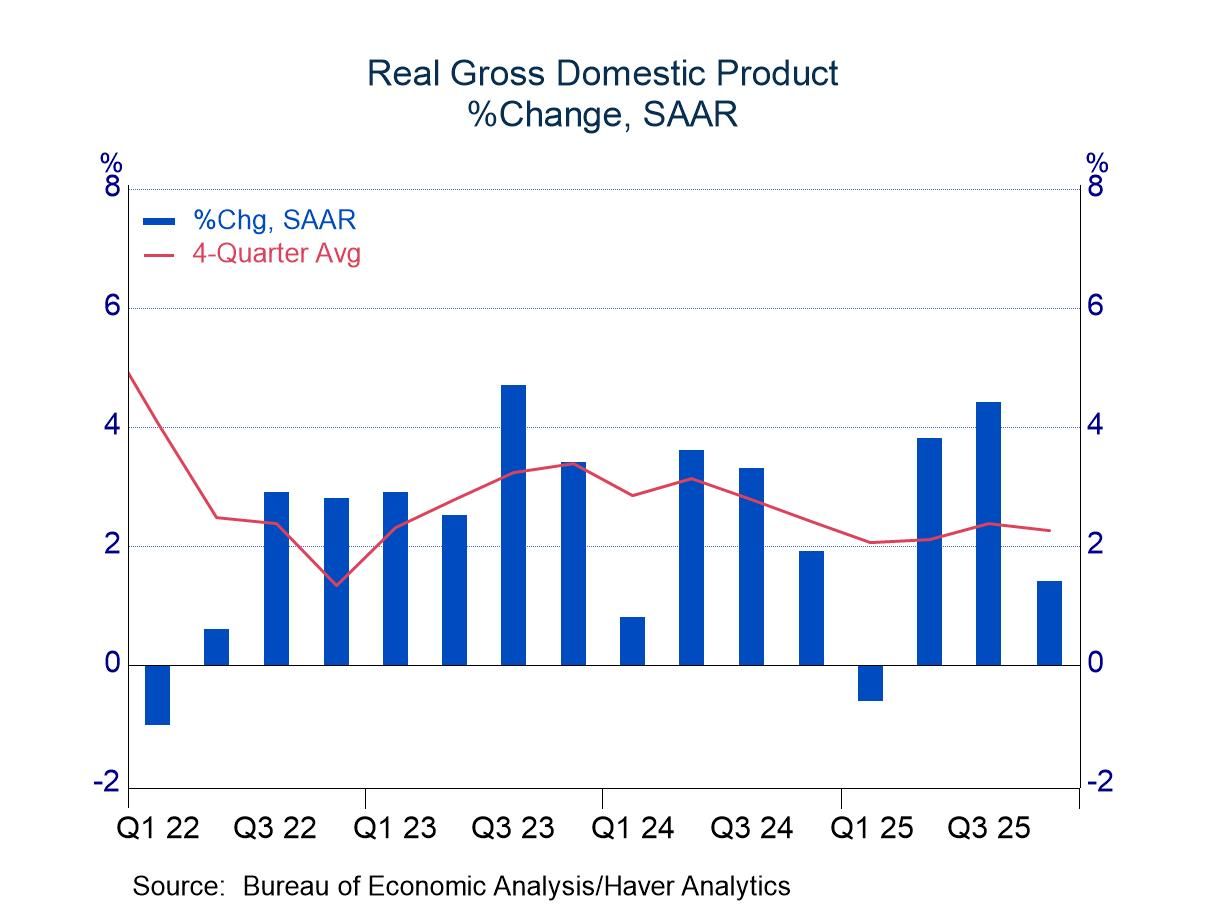

Indonesia’s Q3 performance Indonesia experienced slightly slower GDP growth in Q3, of 4.9% y/y, registering its first sub-5% growth reading in seven quarters (chart 1). The main support for Indonesia’s Q3 GDP growth stemmed from private consumption and gross capital formation, which collectively contributed to 4.7 percentage points of growth. Also, net exports provided a slight lift to growth, while government consumption exerted a mild drag.

Chart 1: Contributions to Indonesia’s year-on-year GDP growth

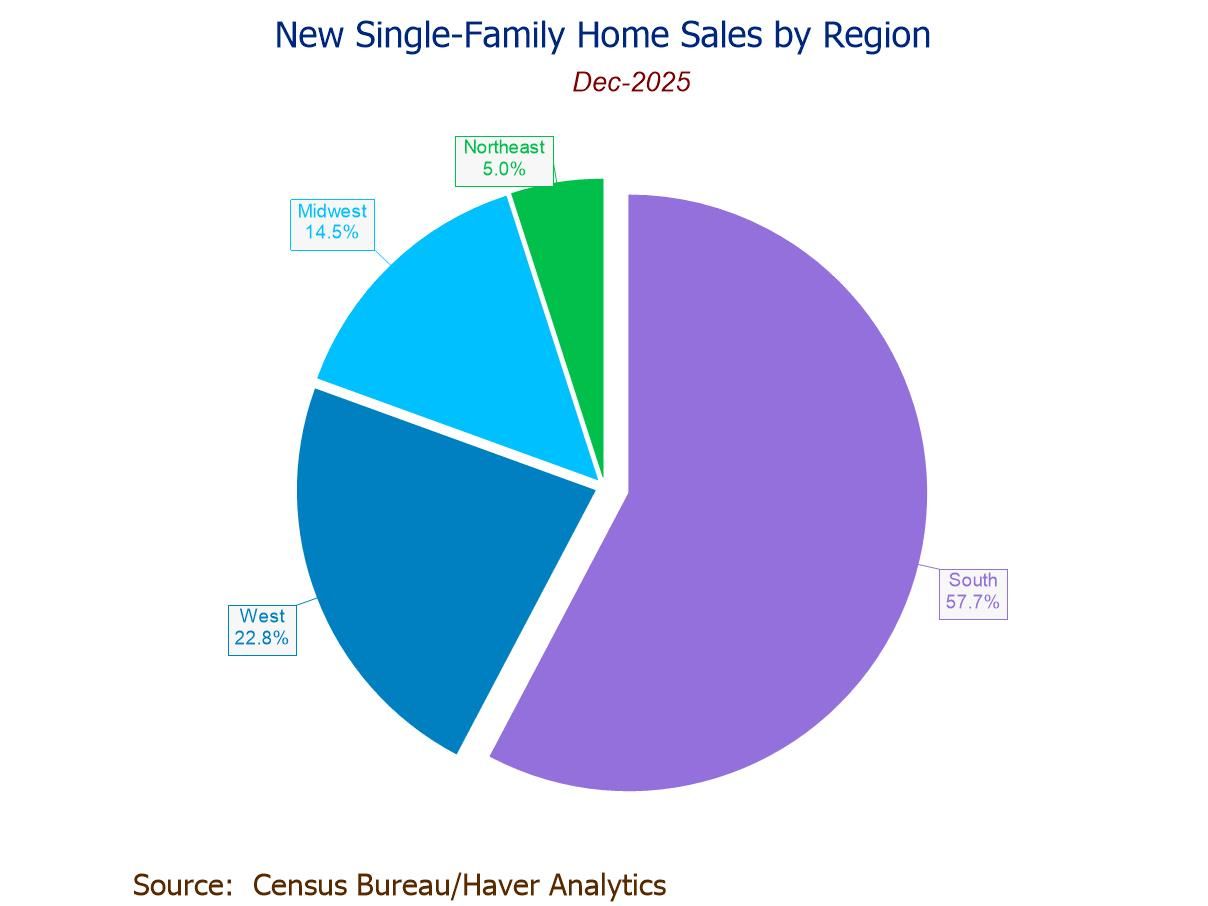

Much of Indonesia’s private consumption growth was driven by the transport and communications sector (chart 2), amid double-digit motorcycle sales growth even as sales of other vehicles fell. The restaurant and hotel sector supported private consumption growth too, albeit more moderately, partially bolstered by sustained tourist arrivals and hotel occupancy rates over Q3. Meanwhile, growth in gross capital formation was driven almost entirely by investment in buildings and vehicles, while machinery and other equipment suffered mild-to-moderate divestments.

Chart 2: Drivers of Indonesia’s GDP growth

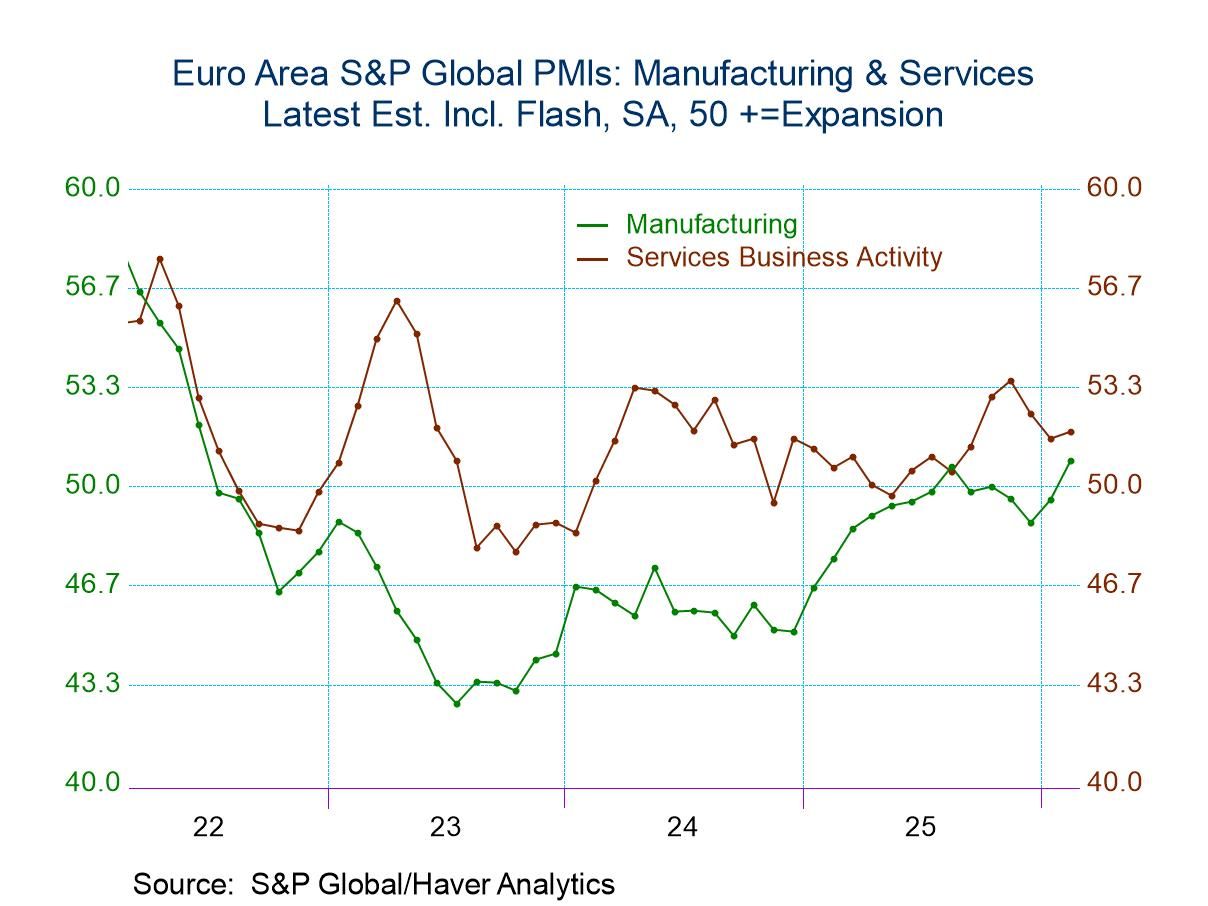

Indonesia’s exports Indonesia saw modest growth contributions from trade in Q3, however, as growth in exports barely outpaced that of imports. While services exports underwent continued robust growth in Q3, revenues from non-oil goods shipments abroad suffered as global commodity prices fell. In particular, export prices of base metal products, palm oils, and coal extended their downtrend during Q3 even as demand held largely steady (chart 3). Looking ahead, the economy faces continued downside trade-related risks in the face of soft export prices and imminent regulatory shifts. For instance, Indonesia’s palm oil exports will likely encounter some obstacles from the European Union’s deforestation rules, which are set to kick in from end-2024.

Chart 3: Indonesia’s export prices

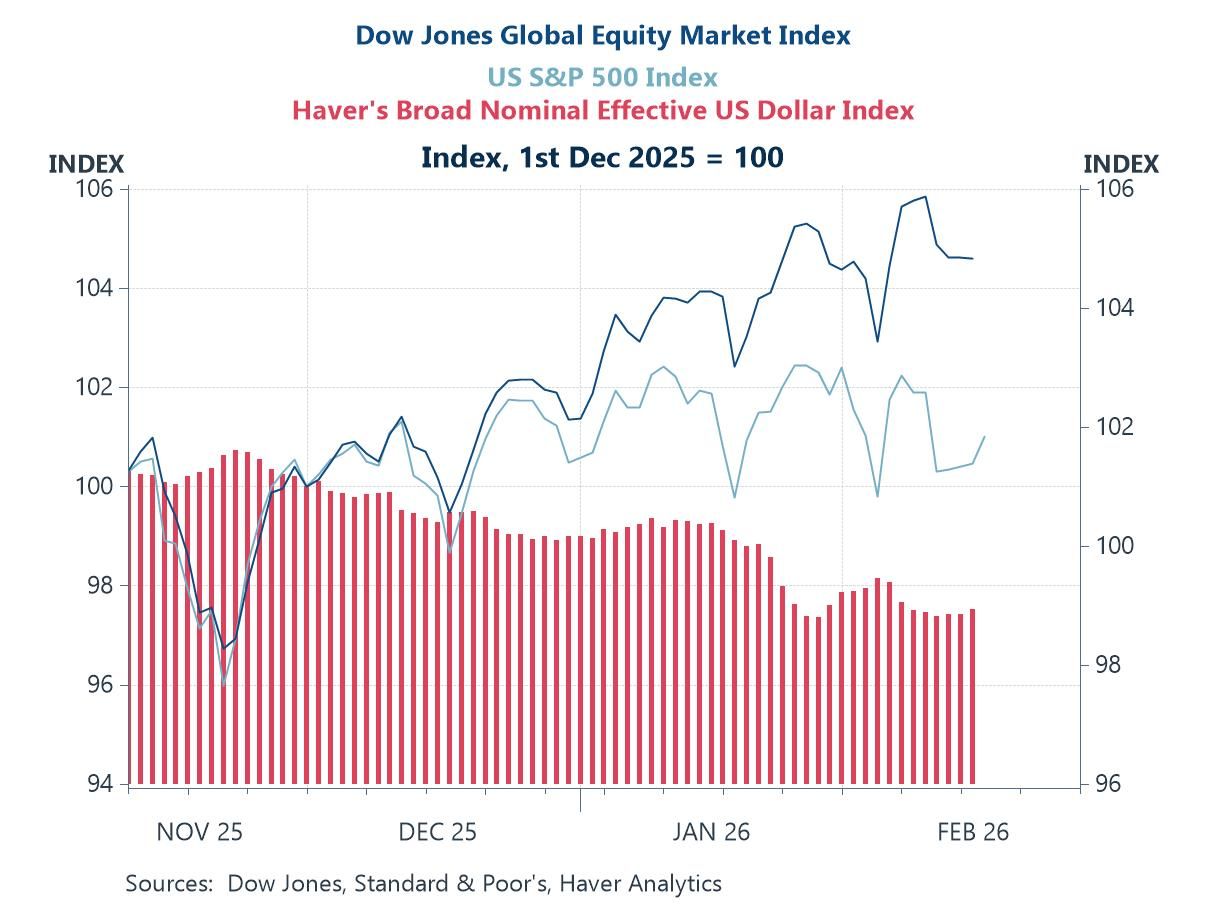

Indonesia persists with its attempt to climb the commodity value chain, however, by restricting exports of certain raw metals while encouraging firms to move production facilities locally. Earlier in June, the Indonesian government effected an export ban on bauxite in a bid to draw investment into the development of local processing facilities. The move follows the government’s 2020 export restriction of nickel ore, which is a key raw input for the production of Electric Vehicle (EV) batteries, among other uses. Indonesia’s nickel restriction was arguably a success, as processed nickel exports (HS code 75) surged in the following years alongside domestic investment in the mining and metals industries. With that said, Indonesia’s success with nickel may have been tied to its dominant position as a producer (chart 4), with limited alternative suppliers available. As such, the country may see weaker results with similar bans on materials it holds less influential production shares of.

Chart 4: Indonesia’s share of base metal production

The Indonesian rupiah and debt flows The Indonesian rupiah remains one of the best-performing Asian currencies so far this year, alongside the Indian rupee, Singapore dollar, and Philippine peso. The currency’s relative outperformance comes despite depreciation pressures arising from the strength of the US dollar. The latter however has stalled following the Fed’s November meeting off dovish market perceptions. Among other drivers, the rupiah’s resilience is partially attributable to moves taken by Bank Indonesia (BI) to stabilize and support the currency. For one, BI has been intervening in both spot foreign exchange (FX) and domestic non-deliverable forward (DNDF) markets to curb episodes of excessive rupiah volatility. The interventions, however, have put a strain on Indonesia’s reserve assets, which fell to $133 billion in October, an 11-month low.

Chart 5: Indonesian rupiah performance vs. US dollar

Direct FX interventions aside, BI has also recently bolstered its array of monetary policy tools with the introduction of Bank Indonesia Rupiah Securities (SRBIs). Unveiled in August and first issued in mid-September, SRBIs are aimed in part at drawing foreign portfolio inflows, being tradeable by non-residents on the secondary market. Response to the new instruments has been moderate to positive, with every SRBI auction so far having been oversubscribed. Further, SRBI purchases by non-resident investors on the secondary market have been sizable, with holdings already totaling about 17 trillion rupiah ($1.1 billion) in early November. With that said, and while the SRBI instruments have enticed some foreign inflows, Indonesia faces continued capital outflow risks. Specifically, non-resident investors have unloaded about 37 trillion rupiah ($2.4 billion) of government bonds in recent months, as Indonesia’s yield differentials against the US turned less favorable.

Chart 6: Foreigner holdings of rupiah-denominated government securities

Tian Yong Woon

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Tian Yong joined Haver Analytics as an Economist in 2023. Previously, Tian Yong worked as an Economist with Deutsche Bank, covering Emerging Asian economies while also writing on thematic issues within the broader Asia region. Prior to his work with Deutsche Bank, he worked as an Economic Analyst with the International Monetary Fund, where he contributed to Article IV consultations with Singapore and Malaysia, and to the regular surveillance of financial stability issues in the Asia Pacific region.

Tian Yong holds a Master of Science in Quantitative Finance from the Singapore Management University, and a Bachelor of Science in Banking and Finance from the University of London.