Asia| Oct 16 2023

Asia| Oct 16 2023Economic Letter from Asia: On El Niño

This week we turn to ongoing El Niño climate conditions and resulting implications for food prices and policy responses in Asia. El Niño effects have already started to depress crop yields in the region, with major producers such as India reeling from poor rice harvests. Consequent food shortages have exacerbated inflationary pressures in Asia, presenting renewed problems for authorities. Regional governments have responded with a range of measures, from price caps to import subsidies and even outright export bans. The scope for a major response from many governments in the region is limited however by the lack of fiscal policy space. Stimulus programs that were enacted during the pandemic have led to ballooning government deficits and debt in a number of economies in recent years. However, central banks face their own set of challenges too. By tightening monetary policy again to fend off renewed inflation challenges they could further tighten financial conditions, from already restrictive territory, and thereby hasten the onset of recessions.

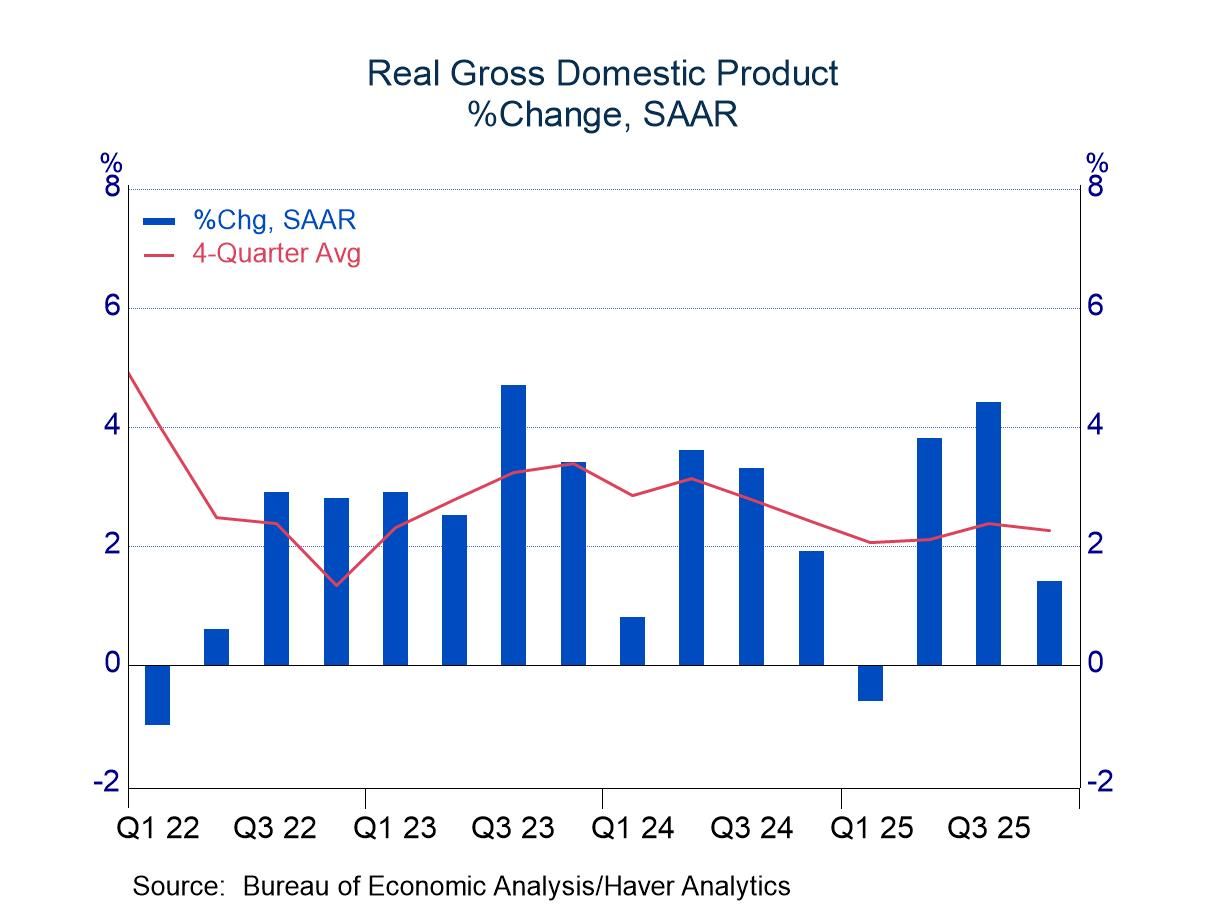

El Niño effects Several Asian economies are expecting reduced crop yields this year, due to impacts brought about by ongoing El Niño conditions. El Niño conditions are associated with warm Pacific sea surface temperatures, accompanied by warmer-than-average sub-surface temperatures and reduced wind pressures in the eastern Pacific. The conditions usually result in reduced rainfall and increased temperatures, affecting regional crop yields and water supplies. Meteorological services around the world observed El Niño conditions to have started as early as June this year, expecting conditions to strengthen into 2024. Across crop types, rice has become of particular regional interest recently, given Asia’s dual role as the world’s main consumer and supplier of the commodity (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Main global rice suppliers

Rice supply-related concerns worsened in late-July, after India – the world’s largest exporter of the good – froze exports of non-basmati white rice on fears of domestic shortages. The country then introduced a 20% duty on parboiled rice exports later in August. Meanwhile, Thailand and Vietnam – the world’s next largest rice exporters – ramped up their rice exports in an attempt to fill the resulting supply gap (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Asia’s rice exports

Crop-related issues aside, the ongoing El Niño is also indirectly affecting air conditions in Southeast Asia, as regional forest fires become more commonplace. Specifically, the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre described the region’s current hotspot and haze situation as “the most intense since 2019”, influenced in part by “current El Niño conditions”.

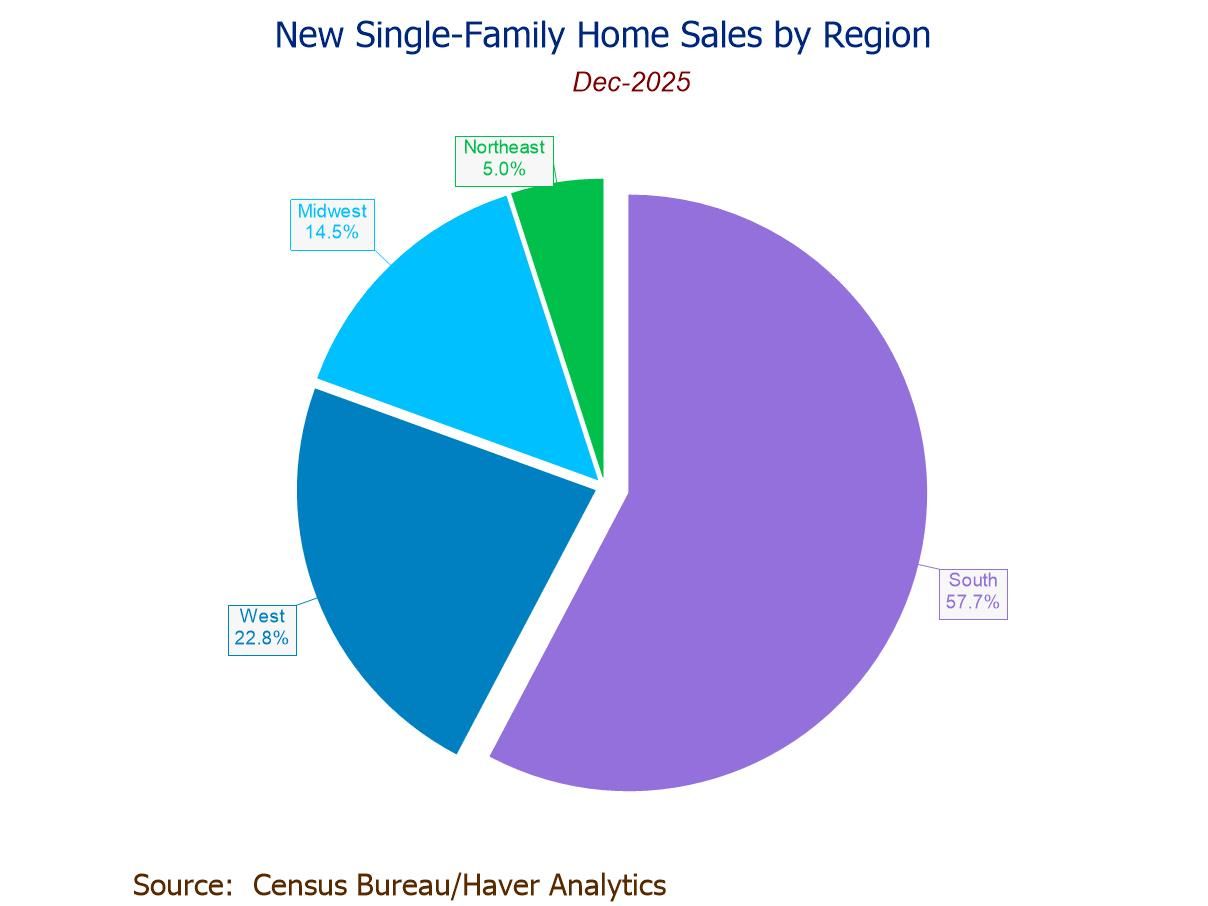

Responses to El Niño Regional governments have adopted a myriad of approaches to combat the adverse effects wrought by El Niño. For one, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia have utilized cloud-seeding to mitigate water shortages and droughts arising from diminished rainfall. To alleviate increasing rice costs borne by retailers and consumers (Chart 2), Malaysia has also introduced import subsidies for certain states and limited purchase amounts. The Philippines introduced a rice price cap in September to address surging prices, but removed it about a month later.

Chart 3: Rice price inflation in Asia

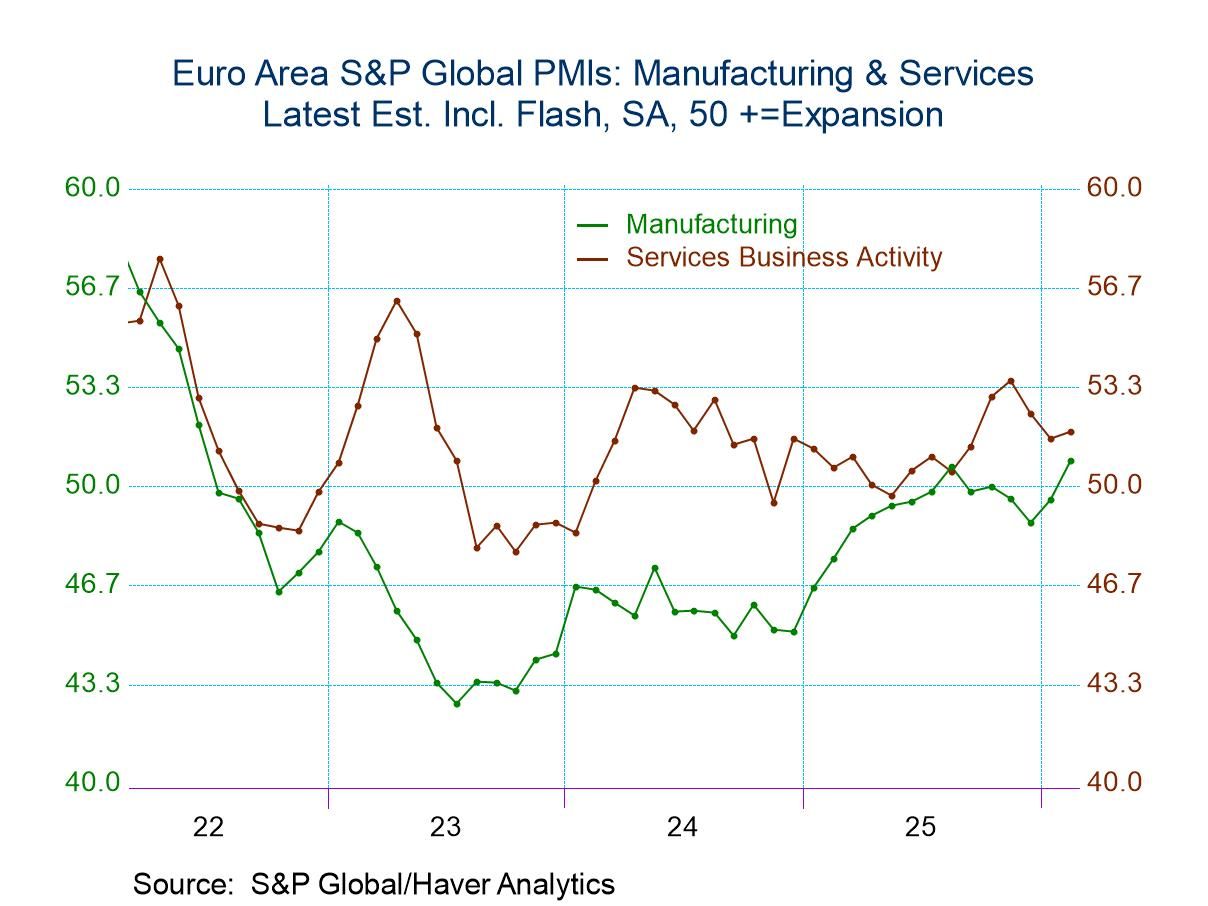

Consequences of price caps, subsidies While price caps and subsidies may address food-related inflation pressures in the near-term, such measures may be costly to maintain over the long-term. For producers, price caps can sometimes create market distortions and put a strain on profits, particularly when costs of inputs (e.g., fertilizers) are also on the rise. When prolonged, the reduced profits may discourage producers from producing altogether. For governments, subsidies can exert a significant fiscal burden especially when market prices continue rising while price caps remain fixed. As such, heavily-indebted governments, especially those of food import-reliant economies (Chart 3), may find themselves having limited fiscal scope to maintain subsidies over prolonged periods.

Chart 4: Asia’s government indebtedness vs. food & beverage imports

Economic risks faced by food exporters Food exporters face economic risks from El Niño too, by way of reduced incomes, should export prices fail to rise sufficiently to make up for reduced shipment volumes. Thus, Asian economies who derive significant revenue from agriculture, such as India, Thailand, and Vietnam (Chart 4), stand to have much to lose should crop yields disappoint and hurt export capacities. There is still much to monitor in this space, given that El Niño conditions are expected to strengthen through the rest of the year and even into early-2024.

Chart 5: Agriculture’s share of GDP in Asia

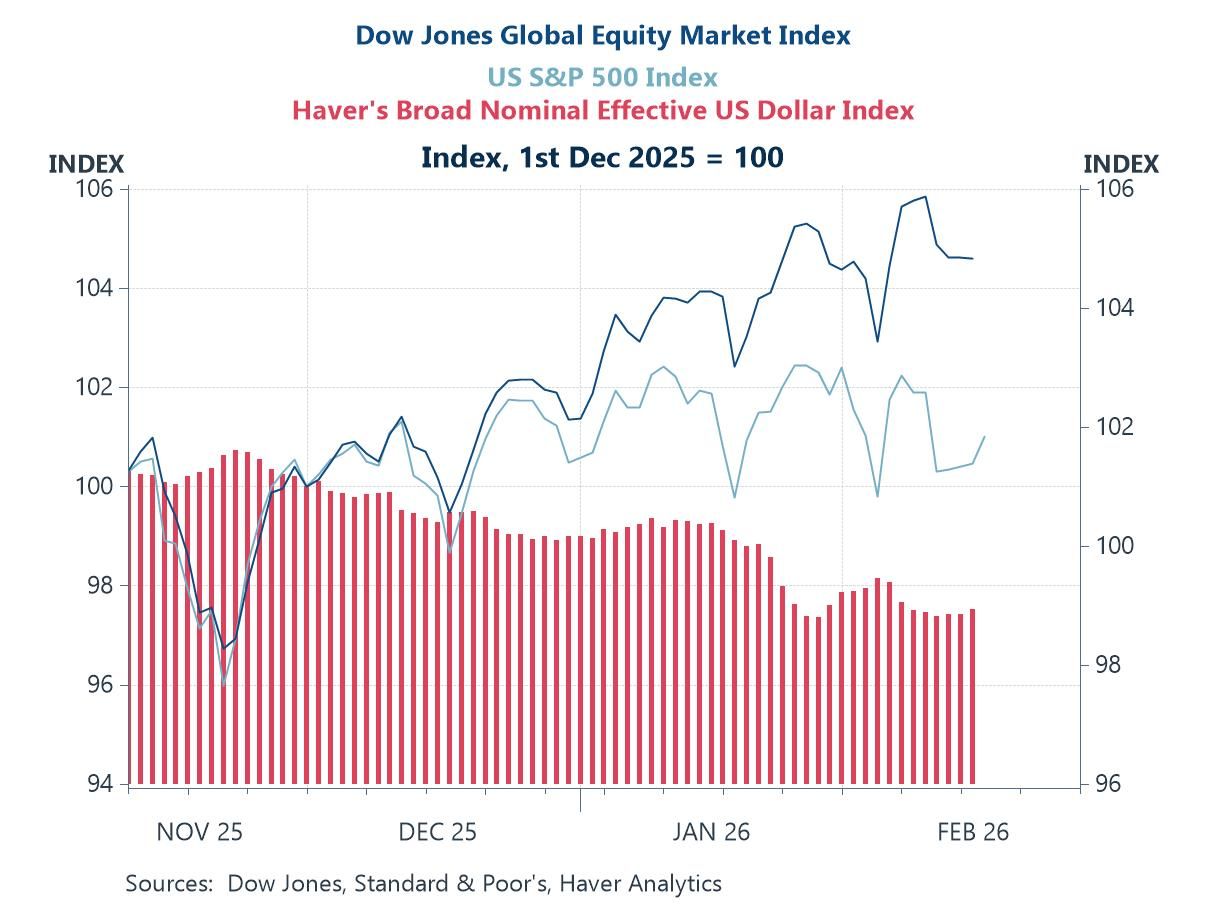

Implications on monetary policy The ongoing El Niño could spawn some complications for monetary policy. On the one hand, central banks may feel pressured to stifle inflation, while on the other, they may fear being overly restrictive on growth. On balance, most central banks in emerging Asia are looking likely to keep their policy rates steady through the rest of the year after having normalized policy in recent months. The Philippines is an exception, however, as it looks to tackle double-digit price inflation of staple food products like rice and vegetables. Further out, Thailand may opt to raise rates further in 2024, subject to domestic demand and tourism outcomes next year.

Chart 6: Policy rates in Asia

Tian Yong Woon

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Tian Yong joined Haver Analytics as an Economist in 2023. Previously, Tian Yong worked as an Economist with Deutsche Bank, covering Emerging Asian economies while also writing on thematic issues within the broader Asia region. Prior to his work with Deutsche Bank, he worked as an Economic Analyst with the International Monetary Fund, where he contributed to Article IV consultations with Singapore and Malaysia, and to the regular surveillance of financial stability issues in the Asia Pacific region.

Tian Yong holds a Master of Science in Quantitative Finance from the Singapore Management University, and a Bachelor of Science in Banking and Finance from the University of London.