Global| Jun 21 2024

Global| Jun 21 2024PMI Services and Manufacturing Backtrack Broadly in June

The flash readings for June in the S&P Global PMI indexes show widespread weakness, but the U.S. dominates whatever month-to-month improvement there is, showing gains in the composite, manufacturing, and services month-to month. Among other June entries in the table, only the U.K. has a month-to-month gain and that's for its manufacturing sector.

This is a clear switch from May when only eight sectors showed weakness out of the 21 sector entries for these seven reporting units each reporting 3 sectors. April also showed strength with only 5 of 21 sectors showing weakness and three of those being in the U.S.

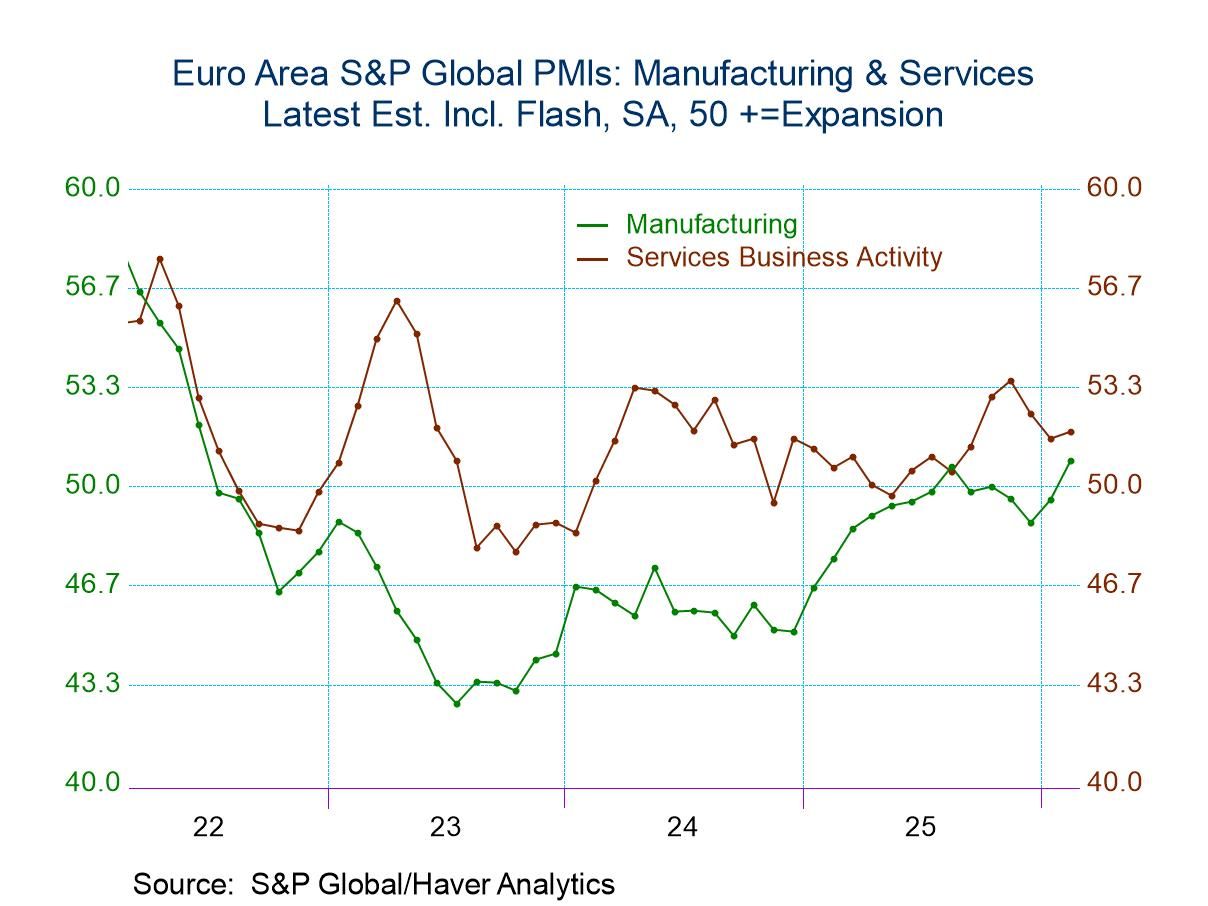

Broader trends Average data, which are calculated only on the hard data which means they're updated through May, show the three-month averages weaker than the six-month averages. Only three sectors weaken over three months; those are the service sectors for the U.S. and for Japan plus a weaker manufacturing sector in Germany. Over six months compared to 12 months, there are six weaker sectors. All three sectors in Australia are weaker; and in Japan, the composite and the manufacturing sectors are weaker; in the U.S., the services sector is weaker. However, over a year compared to the year previous, there are only 5 sectors that are stronger. The chart at the top gives you a sense of the roller coaster ride that the PMIs have been through for services and manufacturing in the European Monetary Area.

Trend shift? The manufacturing data in the chart has been on a plateau for about 5 months while the services sector in the monetary union has only just begun to turn lower in the past two months. The question is whether there is some sort of new trend in place and whether the upswing is over. It's too soon to know this, but it's not too soon to wonder about it.

The global monetary cycle Global monetary policies have basically concluded their tightening phases as central banks have moved into a position of either neutrality, easing, or of teasing an easing. The Bank of Japan and the Federal Reserve are still holding their fire. The Bank of England is giving hints as the Fed has done that there could be rate reductions ahead. The ECB has cut rates once and then signaled that it will be on hold for a while. This week the Swiss cut rates for a second time. In the meantime, inflation progress has slowed, stalled, or engaged in some minor backtracking. This has raised some new question marks around what central banks plan or what they'll be able to do in the future.

Inflation Inflation has been over the target top in Western economies for three-years running. Japan has had excessive inflation for about two years. Even now, inflation remains above the 2% targeted by major monetary center central banks. However, central banks showed that they are having greater sensitivity to unemployment and have either signaled or engaged in rate cutting to support economic stabilization even after a prolonged period of inflation overshooting and before inflation has come into target. This raises questions about what monetary policy will do in the period ahead.

The policy dilemma Central banks continue to (at least verbally) support their existing 2% targets; however, their reluctance to conduct monetary policy in a way that would move inflation back to target more expediently, after a long period of missing, should raise question marks about central banks intentions and resolve. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve’s explicit attempt to create a soft landing has led to a situation where interest rates have been held above normal levels for a long time but have not been raised high enough to significantly slow growth or push inflation back to 2%...yet. This policy has been having an adverse impact on the housing market and has contributed significantly to increased debt servicing costs by the federal government where debt-to-GDP ratios are high and have been rising. The Federal Reserve’s attempt to create a soft landing has not been without its cost, and recently the rise in the unemployment rate has triggered another recession signal since the unemployment rate has risen by more than 1/2 a percentage point from its cycle low. If the U.S. were to run a recession after having paid the price that it's paid to try to achieve a soft landing, that would be bad news indeed. And there are ‘other risks’ as well. U.S. monetary history is clear. When the Federal Reserve has been unwilling to stick with rate hikes or has raised rates less than it should have, or when it has raised rates aggressively but not held them high enough long enough, inflation has not come to heel. U.S. monetary history strongly suggests central banks need to reduce inflation to or close-to their desired level before cutting interest rates or they run a substantial risk of having inflation return and having it rise from an even higher level than it had before its previous acceleration commenced.

Risks ahead will loom even larger With elections in the U.K. and elections on the horizon in the U.S., monetary policy begins to enter a certain ‘twilight zone’ of uncertainty. Monetary union countries have their own political shifts to deal with as member countries in the EU appear to be dealing with a shift to the right across European elections to the European Parliament. To what extent, these are repeated in domestic political circles has yet to play out. France will be the next country to find out. The combination of a slip up with inflation, rising debt levels, and war on Europe's borders magnifies risk and sets new precedents. There is a need to rebuild military capabilities; that will be putting pressures on political systems in Europe as well as globally. The peace dividend appears to have been spent and yet, across countries, there remain significant social welfare goals that, as yet are unachieved. This is a prescription for continuing political clashes and continued tension to be placed on monetary policy. In this environment when fiscal policy would appear to be under some great strains, it will be extremely important for monetary policy to fight the forces of inflation that remain that may even be welling up with greater intensity. This is no time for central banks to think that inflation is going to fall back to 2% by itself under the pull of gravity. Gravity does not apply to inflation. Although we can answer the question, war, what is it good for? The answer is to stoke inflationary pressures.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.