Global| Oct 03 2017

Global| Oct 03 2017EMU PPI Accelerates In August...But Does It Matter?

Summary

The EMU PPI is accelerating in August. But its 0.6% gain follows a 0.1% drop in July. The PPI continues to be volatile. Its trend is hard to nail down. And gyrating oil prices have great impact on the path of the PPI. The unrelenting [...]

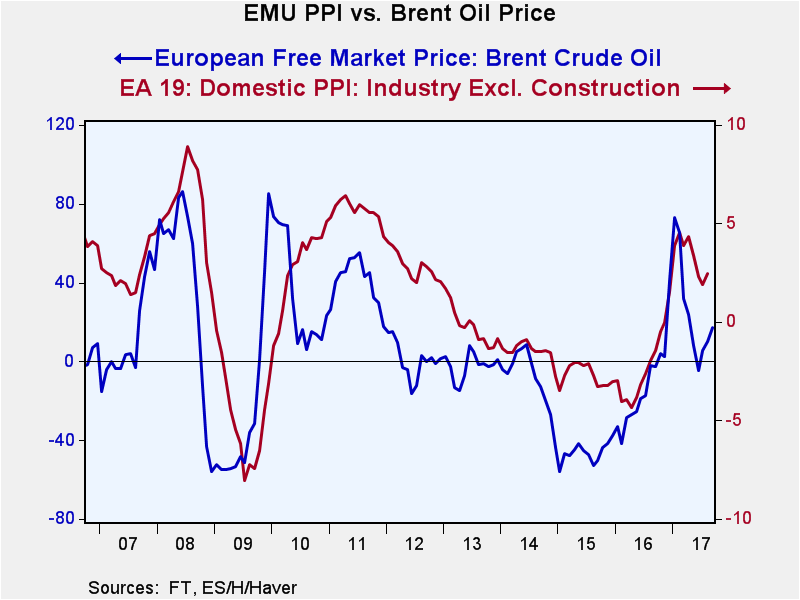

The EMU PPI is accelerating in August. But its 0.6% gain follows a 0.1% drop in July. The PPI continues to be volatile. Its trend is hard to nail down. And gyrating oil prices have great impact on the path of the PPI.

The unrelenting and undiminished role of oil

Oil continues to dominate the outlook for the PPI and the outlook for oil is muddied. We are coming off a period in which oil prices have firmed. Yet, for the fifth straight month, bankers have cut their outlook for oil prices. On the day, oil prices slipped taking Brent to $58.08 per barrel. Russian Energy Minister, Alexander Novak, today claimed there was no immediate need to talk about further oil output cuts. As a result, the outlook for oil continues to be uncertain and U.S. rig activation is back on a positive path after some slowdown.

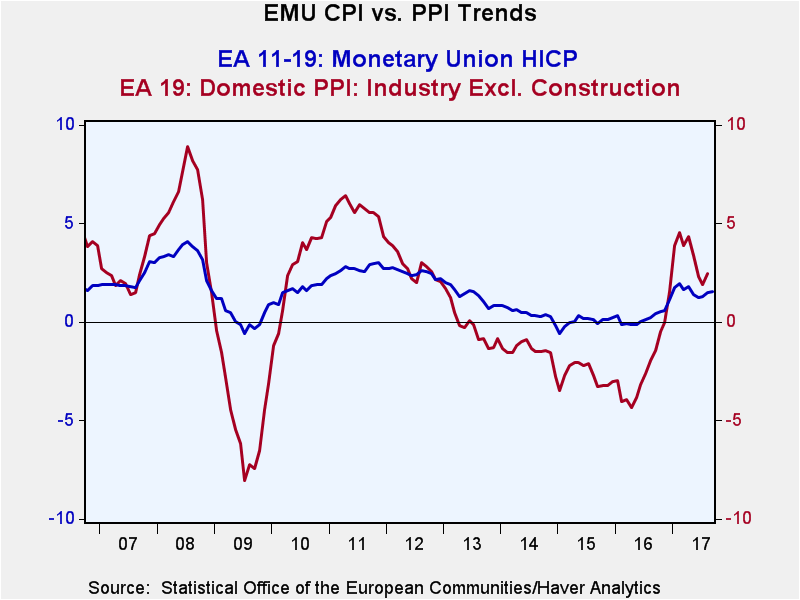

The policy focus is not the PPI

As always what matters for policy and for the ECB is what happens to consumer prices and the HICP measure that the ECB uses. The relationship between consumer prices and producer prices in the EMU is a loose one. When the PPI makes an exceptional move, there is usually some impact on the HICP but one that is muted. With oil prices suddenly having swung higher after a substantial period of declining, there has been some lift in the pace of the HICP but the headline and core rates continue well under the objectives set by the ECB. More recent news on EMU area wages show that wage increase have popped up to log a 2% gain. But it will take time to see if that move has any sustainability or follow-up or not.

Month-to-month

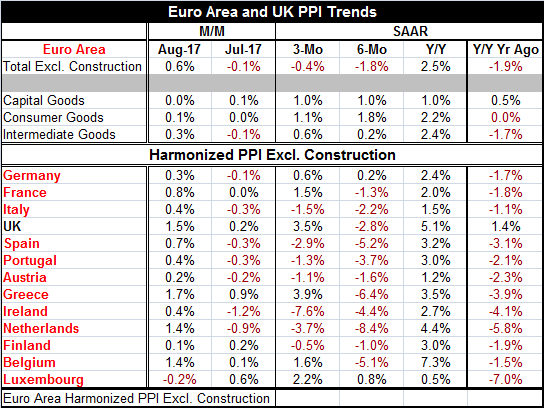

Compared to July, the PPI is accelerating in all EMU reporters in the table except the financial center Luxembourg and Finland. Prices only fell in August in Luxembourg. Still, prices did fall in seven of 12 of these EMU countries in July.

Sequential trends

Sequential growth rates 12-month to six-month to three-month show that inflation is up at a 2.5% pace over 12 months, but it is still showing price declines at a -1.8% annual rate over six months. Over three months, that pace is trimmed to -0.4% (SAAR).

Sectors

Sector rates of growth show stability in price trends for capital goods locked in at a pace of 1%. Consumer goods price inflation is still sequentially falling. The pick-up for inflation is wholly from six-month to three-month and in intermediate goods, where oil prices pressures show up. On balance, despite some increase in activity in the EMU and optimism over growth, inflation is really only picking up in intermediate goods not for capital goods and not for consumer goods: it's still an oil phenomenon.

Shifting relationships

In the U.S. where I have looked at the PMI growth 'phenomenon' more closely, I have discovered a shift in the relationship between the PMI and industrial production growth. It seems in this expansion at each growth rate for IP the corresponding PMI value is higher that it used to be. So while some speak of more 'buoyant economic reports' to me the PMIs are just another example of shifting and less meaningful economic relationships, like for the Phillips Curve. For some time, we have known that dropping unemployment rates should have created more wage and price inflation except they didn't. Still, policy in the U.S. remains geared to the Phillips Curve. Judging from the strong-seeming PMI readings, IP and the industrial sector would be expected to be much stronger, but it isn't. Not surprisingly the strong PMIs are taken as further evidence that Phillips Curves will come back to life. Some hopes spring eternal.

Decoupling and denial: square pegs vs. round holes

In fact, in Japan today, following the stellar Tankan report released yesterday, Japanese firms actually pulled back on their inflation expectations in Q3. Companies there now expect consumer prices to advance by 0.7% in the year ahead instead of 0.8% as they did previously. This is just another example of decoupling. Old economic relationships are shifting. Central banks have their eye upon the hole and not upon the donut. They don't even realize that they are not watching that which has become less important. They remain eerily clueless or in denial about how the world has changed. Even when they admit out loud that they may be missing something, they do that just to cover their bases and continue to make policy as if the relationships of yore will spring back to life spontaneously. Well, who knows what they think at this point. Central bankers are not prepared for the great game of no-or-low inflation to go on. They are prepared for it to end; for normalcy. They warn of inflation overshooting when target-achievement might be their best-case scenario. Most importantly they have no plan 'B.' They are determined to pursue plan 'A' and to find different ways to justify it, such as the Fed's 'clever' plan to justify the start of tightening in the midst of a huge inflation undershoot as oil prices collapsed by appealing to its medium 'forecast.' The square peg of Fed policy has yet to find a round hole of reality that it could not be forced though. We are now waiting on Europe to see how things will go there.

Myopia makes policy choices easier... but makes them more dangerous

To me the global inflation shortfall is a true global phenomenon. It is not a bunch of idiosyncratic local events that simply happened to occur at the same time (surprise!). The first warnings came out of Japan and as everyone commiserated with Japan's problems and offered advice from afar the problem nonetheless spread. Some were sure that Japan's bout with deflation was all because of Japan's unique demographics. How did that one play out? Now we are assured that disinflation is no longer a problem. But with oil prices having ratcheted back up with so little overall impact, I'm not sure that is a conclusion that could stand up to close inspection. There are some slight wage pressures afoot in the EMU and in the U.S., but they are very slight and have yet to show staying power let alone escalation. And there is some unemployment backsliding in Spain reported today. If that sort of thing continues and spreads, wage pressures will be central banks' last worries. We are still not that long or far out of the soup.

Stirring the pots

The U.S. pot is being stirred by hurricane effects of unknown dimension. In Europe, the Catalan problem has emerged; the feeling that with the German elections over Europe has dodged the bullet of 'populism' has proved wrong. And Germany still will be ruled by a less-united coalition. The same leader will prevail, but different compromises and policies will be afoot. The tensions in Italy with its Five-Star party are still present. The Kurds in Iraq have begun to stir up their own issues to the consternation of (at least) Iraq and Turkey. North Korea is still a big unsolved (unsolvable?) problem and U.S. President Donald Trump is still pressing many on the trade front while trying to enlist some of his 'trade adversaries' into cooperative groups for other geopolitical ends. Global diplomacy has never been so fractured. The geopolitical scene is more topsy-turvy than an owners' meeting in the NFL these days. And that's saying something.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates