Global| Oct 16 2017

Global| Oct 16 2017EMU Trade Surplus Widens

Summary

Imports continue to grow faster than exports in the EMU which has been the case since late-2016. Yet, the surplus is barely changed from 12 months ago. The greater import (compared to export) growth tends to drive the surplus lower [...]

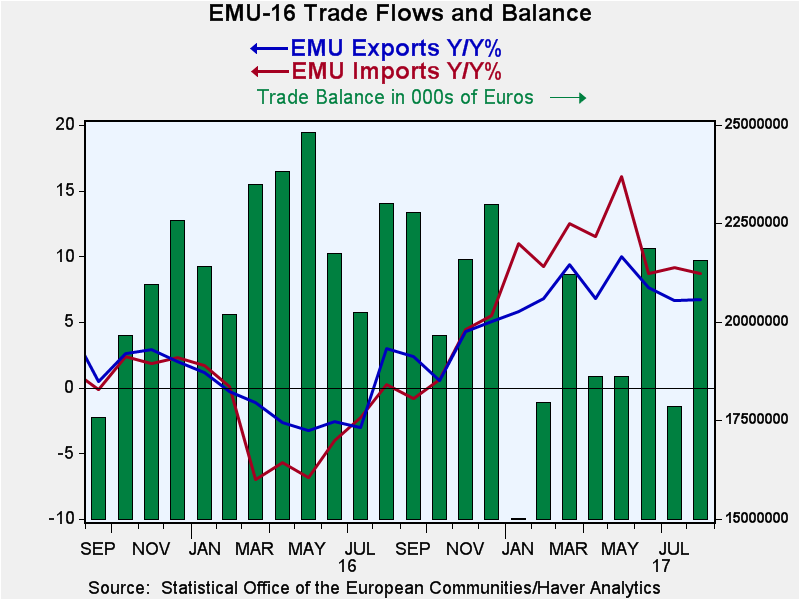

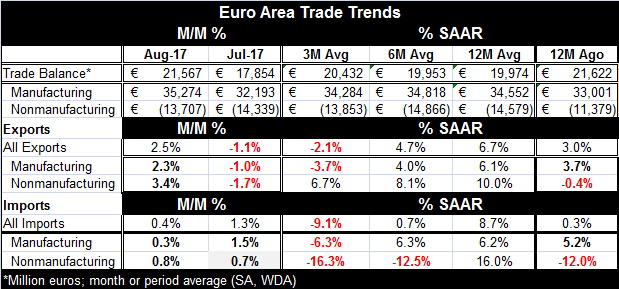

Imports continue to grow faster than exports in the EMU which has been the case since late-2016. Yet, the surplus is barely changed from 12 months ago. The greater import (compared to export) growth tends to drive the surplus lower from one year ago. But since the trade account is already in surplus (X>M), imports have to grow substantially faster than exports to actually reduce the size of the nominal surplus. The surplus in August 2017 is larger compared to July because exports ran up by 2.5% m/m while imports crept up by just 0.4% m/m. Over 12 months the surplus at 21.567 billion euros is barley lower than its 12-month ago value of 21.622 billion euros. Over 12 months, exports at 6.7% were outgained by imports which rose by 8.7%.

Imports continue to grow faster than exports in the EMU which has been the case since late-2016. Yet, the surplus is barely changed from 12 months ago. The greater import (compared to export) growth tends to drive the surplus lower from one year ago. But since the trade account is already in surplus (X>M), imports have to grow substantially faster than exports to actually reduce the size of the nominal surplus. The surplus in August 2017 is larger compared to July because exports ran up by 2.5% m/m while imports crept up by just 0.4% m/m. Over 12 months the surplus at 21.567 billion euros is barley lower than its 12-month ago value of 21.622 billion euros. Over 12 months, exports at 6.7% were outgained by imports which rose by 8.7%.

While exports and imports both are higher in August and while there is some optimism about a pick-up in trade and growth, the broader sequential growth rates for exports and imports point to a slowdown. Note that also in the trends for year-on-year total export and import growth there has been a longer-lived ongoing deceleration afoot. Both overall export and import trends show sequential slowdowns in trade flows from 12-month to six-month to three-month.

Breaking exports down into manufacturing and nonmanufacturing to isolate oil and other commodities in a separate grouping does not change the trade slowdown result. EMU manufactured exports slow from a 6.1% gain over 12 months to a 4% pace over six months to a -3.7% pace over three months. Nonmanufacturing growth rates also show sequential slowing from growth rates of 10% over 12 months to 8.1% over six months to 6.7% over three months.

For imports the breakdown in manufacturing is also more or less in-line with a slowing as the 6.2% 12-month growth rate ticks higher to an imperceptibly faster 6.3% over six months then plunges to a -6.3% pace over three months. For nonmanufacturing imports, the slowdown is more consistent and dramatic from 16% over 12 months to a -12.5% annual rate over six months to a -16.3% annual rate over three months.

Over 12 months, manufacturing exports are only a tick weaker than manufacturing imports. As a result, the surplus on manufactured trade gets larger over 12 months, rising to 35.3 billion euros from 33.0 billion euros. It is on nonmanufacturing trade that the deficit gets larger.

German, French, Dutch, Finish and Portuguese exports all are weaker on their three-month rates of growth than on their 12-month rates of growth. There has been some broad tendency for exports to slow on the period. As we see in the overall EMU data, that is not all attributable to commodities prices since manufacturing exports and imports also demonstrate the slowdown pattern.

While there is some anxious anticipation of a return to normalcy and of a return to more normal monetary policy-making, it is not crystal clear that the economy has gone over these hurdles. At its recent meeting, the IMF has only nudged up its forecasts although in Germany the outlook have been hiked much more substantially.

There is some step-up in international optimism; yet, it is not clear that this has a solid foundation. The ultra-sensitive PMI data are most consistently giving off strong signals, but in some cases those gains are fading and in the U.S. the two main PMI surveys are at odds with one another. Asia is still not firing on all cylinders. While Europe has some more upbeat data mostly from Germany, it is unclear if the rest of Europe will get any positive spillover from that or not. Brexit issues are still without much progress or clarification. Angela Merkel has lost some of her influence and her base continues to erode in local elections. U.K. politics are on uneven footing. Spain has the Catalonia issue to contend with in addition to its ordinary policy problems. Iraq is in conflict with the Kurds who, like Catalonia, want to slice off their own piece of the pie. The situation in North Korea is not moving toward a solution. Donald Trump's uncertain posture toward Iran is contrary to what the U.S. allies want. All of this intensifies international uncertainties and hardly marks an environment in which I want to extrapolate minor positive economic trends into larger gains for the future.

In short, there are a lot of geopolitical events in flux as economic data show only the most fragile green shoots of growth. Wage inflation also can be detected but only by specialized sniffer-dogs. It is far from clear that wages will continue to show momentum, especially with Asia still so weak and trade slows still lethargic. Meanwhile, central bankers are planning for life after monetary humiliation and hoping that it will start soon. But the optimism is still speculative and failure of the trade data to come on board with accelerating flows is a reminder of where we are compared to where we want to be. Don't get the two confused.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates