Global| Oct 09 2017

Global| Oct 09 2017German IP Makes Strong Rebound

Summary

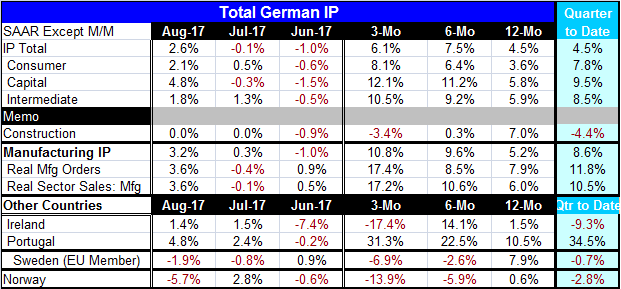

Germany's industrial production rebounded strongly, gaining 2.6% m/m in August after falling in each of the previous two months. Capital goods output was especially strong, rising by 4.8% in August after falling for two straight [...]

Germany's industrial production rebounded strongly, gaining 2.6% m/m in August after falling in each of the previous two months. Capital goods output was especially strong, rising by 4.8% in August after falling for two straight months.

Germany's industrial production rebounded strongly, gaining 2.6% m/m in August after falling in each of the previous two months. Capital goods output was especially strong, rising by 4.8% in August after falling for two straight months.

German industrial output has accelerated from its 4.5% pace over 12 months, but its 6.1% pace of expansion over three months is still a bit weaker than its 7.5% annualized rate over six months. In the quarter-to-date, IP is advancing at the same pace as its year-over-year rate, 4.5%.

Consumer goods, capital goods and intermediate goods output are on steady accelerating paths from 12 months to six months to three months, but overall IP gains are held back by construction which is sinking at a 3.4% annual rate over three months.

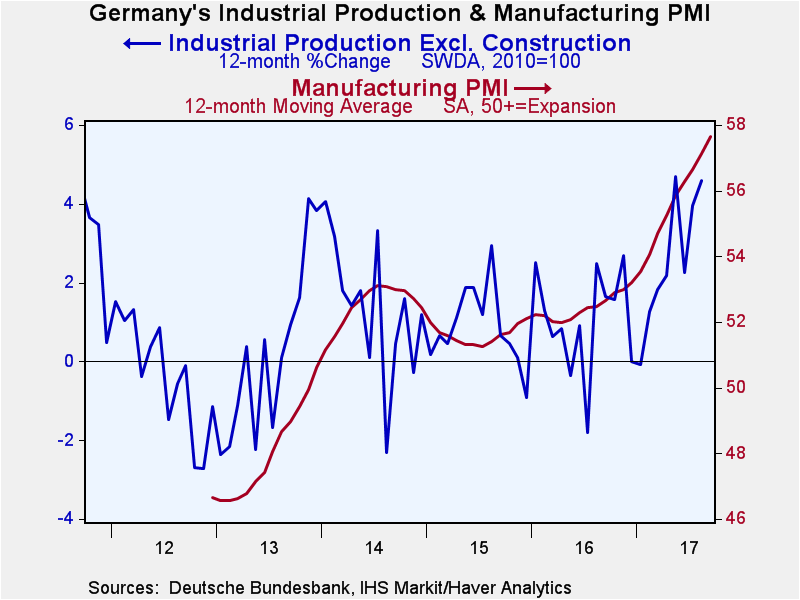

Manufacturing output is accelerating as are real manufacturing orders and real manufacturing sales. The gains track higher over the last year at progressively stronger growth rates. As a result (see Chart), German IP is tracking the gain in its manufacturing PMI rather well right now. Manufacturing output real orders and real sector sales are showing strong growth rates in the quarter-to-date. Manufacturing IP has the weakest pace so far at an 8.6% pace while real orders lead the pack with an 11.8% rate of growth.

Europe on balance

In other early-reporting European countries, the pattern for IP is less ebullient than it is for Germany. Portugal is the exception, having piled on two strong consecutive months and with quarter-to-date sales flying at a 34% annualized rate. While orders are up for two months running in Ireland, they still do not compensate fully for the output drop in June leaving a negative three-month growth rate and a quarter to date rate of growth of -9.5%. Sweden and Norway each show output drops in August and log net output declines over three months as well as over six months. In the quarter-to-date, Sweden's output is shrinking at a thin 0.7% annualized rate. In Norway, output is declining in the quarter-to-date at a 2.8% annual rate. Of course, most of Europe has yet to report, all we have for now are some scattered results from two Northern European reporters, Ireland, Portugal and Germany, the EMU's big enchilada.

Upcoming IMF meeting and beyond

The IMF is getting ready to meet and Christine Lagarde already has thrown down the gauntlet to urge countries not to waste this opportunity of ongoing growth to make some of the needed changes they postponed during recession and in the weaker portions of the recovery. While some growth metrics are looking better, part of that is because of our downwardly revised expectations. Part to it is that job markets have responded better than expected even in the face of relatively low growth. And that is in part because of the low productivity jobs that are the backbone of jobs growth and at the same time a bug-a-boo for central banks because wages have not risen strongly and inflation remains under target everywhere except in the U.K. (i.e., Rolling Stones: you can't always get what you want). Basically, there is a set of economic conditions that rationally support all these trends together. Central bankers are finding that they cannot cherry pick the changes they want (i.e., they have been unsuccessful in raising inflation).

The global economy is growing and there are some signs (largely) from PMI data that growth is picking up but those signals are still not confirmed by accounting-type data. Germany, more or less, shows its IP is in step with its manufacturing PMI, but that does not make it true everywhere else. The U.S., in particular, seems to have its IP and its manufacturing PMI open to different pages; it also has two separate manufacturing PMIs that are telling quite different stories. For now the German industrial data all are looking pretty good, but the rest of Europe is less certain.

Having said that, the Sentix confidence index for the euro area investor has hit a 10-year high. Regardless of 'which data are doing what' investors are becoming more enthused about European prospects. The index rose to 29.7 in October from 28.2 in September; it had been expected to fall.

For now the EMU, the U.S., Japan and the U.K. all are key monetary center countries/regions being supported by extra loose monetary policy. As Christine Lagarde urges countries to make long-delayed changes while growth is still solid or dependable, we have to wonder what the removal of monetary stimulus will do especially since central banks seem ready to engage in this backtracking more or less together. The Fed in the U.S. already has begun to raise the level of rates and now has a schedule under which to shrink its balance sheet. The Bank of England is talking about what it might have to do next referring to a withdrawal of stimulus. ECB members are talking about making stimulus unwinding a feature of policy next year. Only the Bank of Japan does not have an end-to-stimulus on any public docket or forum. Meanwhile, although globally growth has picked up a bit according to PMIs just released, China's private sector growth has slipped in September with its private sector PMI dropping to a three-month low at 51.4 in September from 52.4 in August. That is a strong counterpoint to Germany's strong IP reported today.

There is no view of the global economy that puts it squarely on the straight and narrow dependable expansion path. Despite Ms. Lagarde's urging, we can't really be sure of how durable growth is and what will remain of momentum as central banks remove some of the long held props under this economy. We are still a living experiment of post-recession growth and we are still feeling our way forward on growth rates that in some ways look good and in other ways are very much lacking.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates