Macroeconomic expectations in the ZEW survey backtracked slightly in Germany while improving slightly in the United States in November. The economic situation improved slightly in the euro area and Germany while backtracking in the United States. That's the assessments of the current economic situation and expectations for Germany or the EMU that are moving in different directions in the U.S. and in Germany or in the U.S. vs. the European Monetary Union in November.

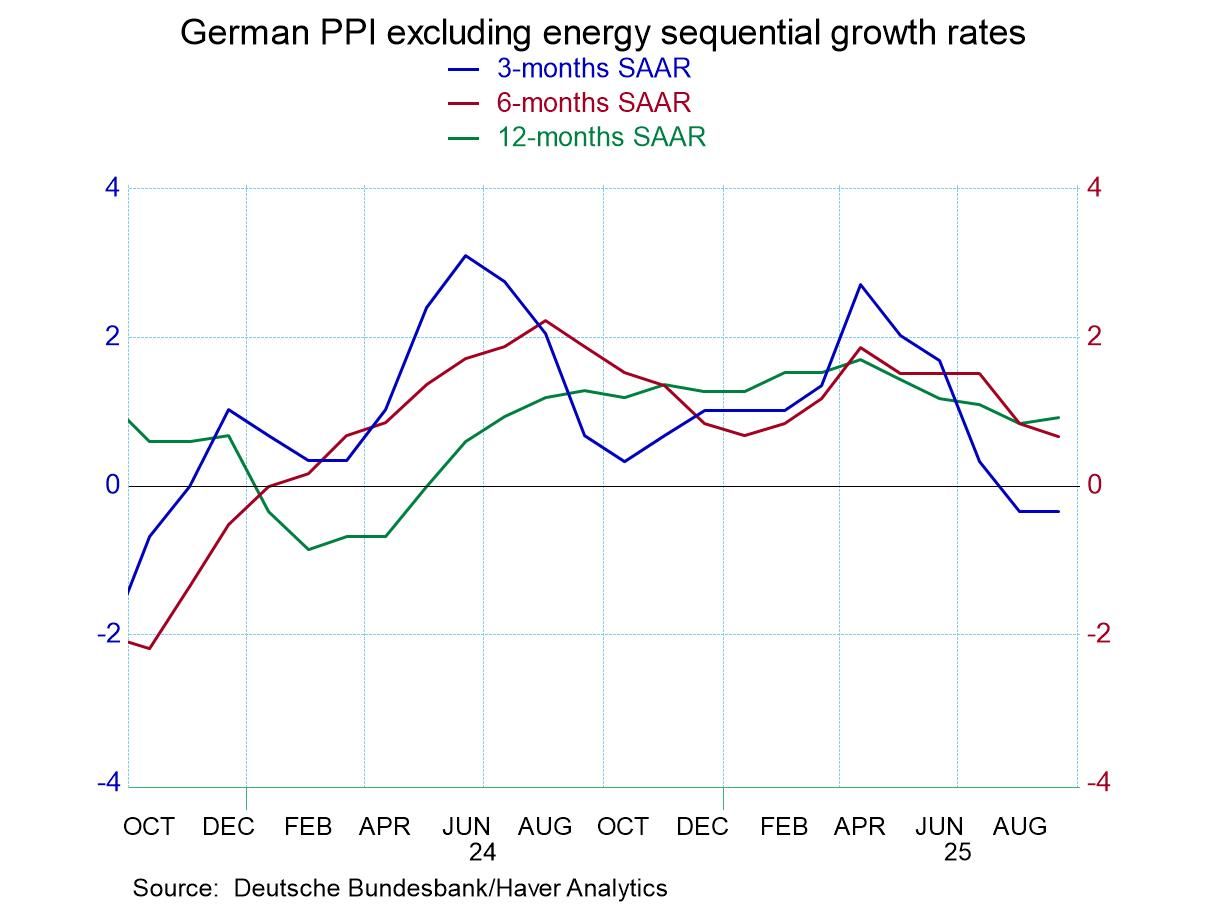

Inflation expectations backed off across the board easing slightly in the euro area, Germany, and also in the United States. While that happened, expectations for short-term interest rates became less focused on rate cuts in the euro area and slightly less tilted toward the expectation for rate cuts in the U.S. as well. Long-term rate expectations receded somewhat in both Germany and in the U.S. in November by small amounts. Stock market expectations picked up in the euro area, Germany, and the U.S., and in most cases, somewhat significantly.

The queue standings The queue standings are ranked standings of these various metrics, and they tell a clear story of how the ZEW experts see current conditions and policy tradeoffs. The euro area has an economic situation where the queue standing is at its 51st percentile, slightly above its historic median (on data since the early 1990s). However, Germany and the U.S. have very weak percentile standings with Germany in its 14.5 percentile and the U.S. in its 35th percentile. Macroeconomic expectations, however, find Germany at a solid 63.6 percentile while the U.S. is at a 23.3 percentile. ZEW experts are far more upbeat on prospects for German recovery right now than in the United States – and that seems odd to me with a lot of fiscal stimulus in train in the U.S. and tons of ‘AI’ investment.

Inflation expectations are high in the U.S. at an 85.5 percentile standing, well above the historic median, and clearly showing threatening conditions. This compares to a 30% queue standing for the euro area and Germany.

Short-term rate expectations are significantly below the median for both the euro area and the U.S. with the euro area at a 26.8 percentile and the U.S. at a 9.3 percentile standing. Long-term rate expectations have Germany at a 43-percentile and the U.S. at a more similar 35-percentile. Stock market expectations are fairly similar across the lot with the euro area at a 38-percentile standing, Germany at a 35-percentile standing and the U.S. at a 38-percentile standing.

Global

Global