Global| Nov 09 2018

Global| Nov 09 2018French IP Backtracks and Falls Year-over-Year

Summary

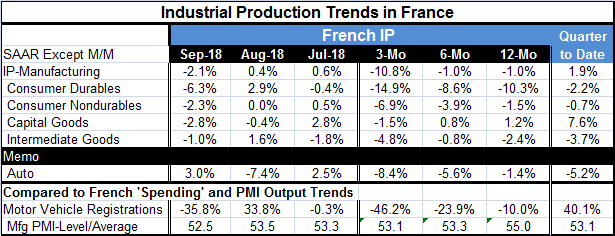

French industrial production (IP) fell by 2.1% in September. It is the largest monthly percentage drop since March 2016. France now shows declines in manufacturing IP over 12 months, six months and three months. The annualized [...]

French industrial production (IP) fell by 2.1% in September. It is the largest monthly percentage drop since March 2016. France now shows declines in manufacturing IP over 12 months, six months and three months. The annualized declines are larger over three months than over six months or 12 months. The loss of momentum and progression of weakness fits with patterns across the EMU and it dovetails with the general signal from France’s manufacturing PMI that says conditions are weakening.

French industrial production (IP) fell by 2.1% in September. It is the largest monthly percentage drop since March 2016. France now shows declines in manufacturing IP over 12 months, six months and three months. The annualized declines are larger over three months than over six months or 12 months. The loss of momentum and progression of weakness fits with patterns across the EMU and it dovetails with the general signal from France’s manufacturing PMI that says conditions are weakening.

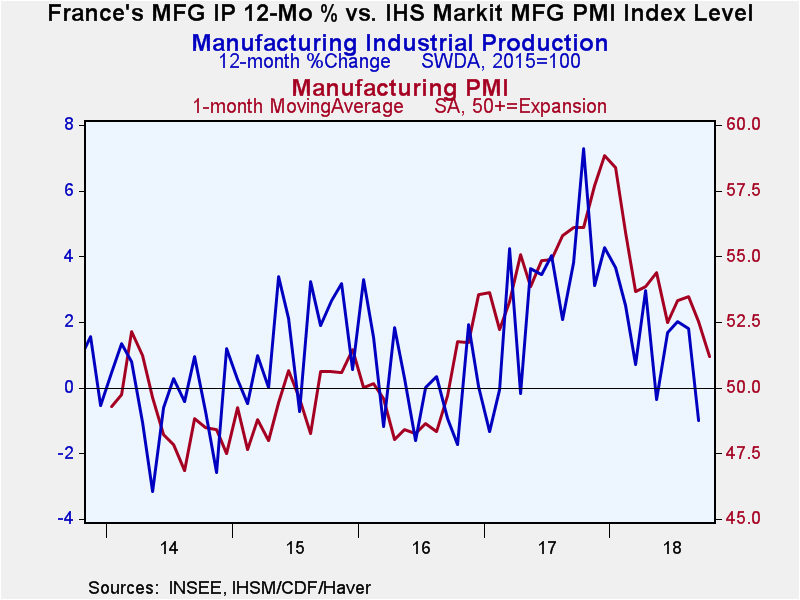

For now, however, the PMI and IP indexes are emitting different specific signals. Both signal a weakening. But while IP is lower over 12 months, the manufacturing PMI has only slipped to 52.5 and does not signal contraction in the sector. If we look at the consistency of those signals back to January 2014, we find that the signal from the PMI and the performance of IP are consistent about two-thirds of the time. That is, when the PMI is below 50, IP is usually falling over 12 months. And when IP is advancing, the PMI is usually above 50. The question for now is whether this is some signaling disconnect or is the PMI signal simply lagging the IP result?

Since 2014 the French ISM has been more prone to give off too-weak signals than to give off too-strong signals by a factor of about 2:1. So the weaker IP result than PMI result is an unusual error. Although the last six errors in this signaling mechanism have come since October 2016 and they have been failures of the PMI to signal contraction when IP actually was contracting.

You can see these episodes on the chart and may note that the first string of misses came as IP was declining year-over-year but was poised to enter an accelerating phrase. The relatively stronger PMI readings were offering the better signal. Recently, however, the situation is the opposite with IP in a declining patch and with the ISM giving us expanding signals (but increasing weaker expansion signals) while the manufacturing IP index vacillates between expanding and contracting but with trends pointing clearly lower.

Clearly, manufacturing in France is still mostly expanding with only two year-over-year manufacturing IP changes over the last 17 months showing negative results (that’s back to May 2017; IP declines are logged February and September 2018). So while growth still carries the day, trend is carrying us closer to a negative result.

However, the PMI readings, if taken less literally, do generally fall into alignment with what IP is doing. And since the French IP series is so noisy (volatile), the steadiness and consistency of the PMI readings can provide some clear sense of where IP is and where it is going. Right now both series point to a slowing in IP and the signal of contraction is hanging in the air, but it is not quite clear that such a single is going to be ratified by the PMI or rejected by it. For one thing, the September IP drop that has taken the IP change into negative territory represents a severe decline and there is often a significant rebound after a drop of this magnitude is recorded. Also the French PMI reading at 52.5 has been declining gradually but is still a long way from signaling contraction unless its pace of decline were to speed up considerably. However, that may just be another way of saying that contraction is coming but will appear farther down the line.

Both IP and PMI gauges track the demise of French momentum

The dynamics across Europe right now are not reassuring although labor market data continue to look solid. We know they are usually not in the vanguard. On the other hand, the euro PMI indexes are showing a lot of backtracking, putting France in ‘good company’ there.

The ECB is in denial about economic weakness and argues that growth is fine. It is still focused on the path ahead that will allow for policy normalization. Yet, trade wars are working their influence and Germany looks to have been caught in the collateral damage from it. That’s not surprising for a country that is so trade dependent. The Baltic dry goods index shows some substantial deterioration in the volume of global trade over the last week alone. Its year-on-year change already has gone flat. China is showing weaker domestic growth but has continued to post solid-looking trade results; still those trade results seem inconsistent with the degree of slowing we see in its domestic economy.

There is a lot of weakness in Europe and France will be one place to continue to watch. Italy already has a batch of its PMI indexes showing contraction for manufacturing, for services and for its composite. The only real pleasant surprise out of Europe in a while has been today’s U.K. GDP report. U.K. GDP rose by 0.6% quarter-on-quarter for its fastest pace in two years. But monthly U.K. data suggest that there is no fire being built under that economy. The U.K. will still have to confront whatever the realities of Brexit will be. So despite the fact that the U.K. has logged some good news, it does not seem to be something Europe can build on. The broadest trend in Europe continues to be encroaching weakness. And despite all the hair-splitting, there is no clear signal on how far the slippage might take it. France seems to be riding the overall European trend, not bucking it.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.