Global| Nov 01 2018

Global| Nov 01 2018Global Manufacturing PMIs Weaken

Summary

Global manufacturing PMIs mostly weakened in October as 10 of 17 reporting countries/regions were weaker on the month. That followed a month in which 11 of 17 weakened and the monthly before when 9 of 17 weakened. Over the last three [...]

Global manufacturing PMIs mostly weakened in October as 10 of 17 reporting countries/regions were weaker on the month. That followed a month in which 11 of 17 weakened and the monthly before when 9 of 17 weakened.

Over the last three months on balance 10 of 17 weakened. Thirteen of 17 weakened over six months compared to 12 months. Over 12 months seven of 17 weakened compared to their levels of one year ago.

This has been a period of broad deterioration in global manufacturing. And the impact of trade conflict is only beginning to be felt.

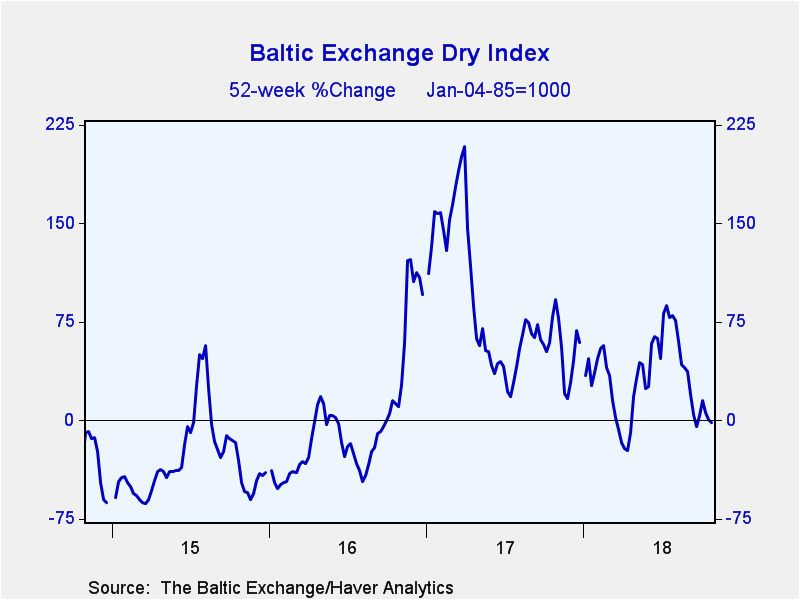

The Baltic dry goods index, an indicator of global trade volume, still does not show much impact on trade. But the pace of trade volume growth year-over-year has slipped to zero.

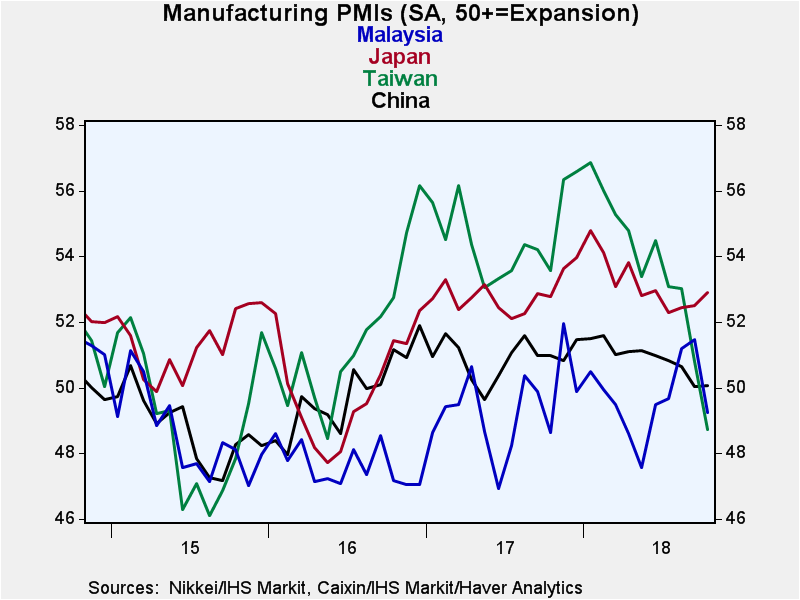

Asia feels the pain

Asia economies are feeling the impact of the global slowdown the most so far. These are economies that have leaned heavily on exports to drive domestic growth. Donald Trump is trying to stop this by forcing countries to trade fairly. So let's take a moment to look at his notion of free- or fair-trade compared to what we have.

What free trade does

We all know that 'Free Trade' is a laudable system with many benefits for all participants. When free trade reigns, people make what they make best and to produce at the cheapest costs and global welfare is enhanced as a result. This is the doctrine of comparative advantage in action. To get there, we need for countries to have some intrinsic differences so that they have advantages. Then we need a market driven systems with market-determined prices and one free of government interference of market operation.

But how much of your stuff do I buy? And how much of my stuff do you buy? This is a pointed question and it is not answered by comparative advantage. Comparative advantage only makes the point that there are gains from trade and that there is a range in which prices can hover to deliver benefits to both parties, if there is free trade.

How much to whom?

The answer to how much is really a question for financial theory. There we look at current account positions of countries and recognize that the equilibrium position in the long run is in balance. So you can buy as much as you sell and sell as much as you buy in the long run. But for interim periods, countries may be better off running surpluses or deficits. The world trading system transitioned to the fluctuating exchange rate system from the previous straight-jacketed Bretton Woods fixed currency system that was based on gold. On a gold standard, when a country runs a deficit, it loses gold; thus, most countries try to eradicate deficits quickly even in the short run to preserve their gold. For that reason, the Bretton Woods system was not very flexible. In the early 1970s, the United States wanted to grow faster than Europe, but if it did that, faster demand growth would spur imports widen the trade gap causing a current account deficit to emerge. U.S. gold would flow out to fund the imbalance.

Unwilling to lose their gold, U.S. authorities went off the gold standard to permit running deficits without the loss of gold reserves. In this new fluctuating exchange rate system, there were a different set of 'rules of the game' than there were under gold. Under the gold standard, the rules of game caused deficit countries to lose gold so they reacted quickly to close a deficit when it arose. But under the new flexible rate system, it was thought that adjustment would fall on the exchange rate.

Instead it hasn't.

Instead, there have been in many cases of NO adjustment.

And many economists have been trying to tell us over the past two decades that that's just fine! We get cheap goods from China and China gets our IOUs – a good deal for us. But is it? How did Greece fare with all is debt? Oh…Greece did not have the reserve currency. True. But at this rate, how much longer will we have the reserve currency? International trade and comparative advantage is NOT about specializing, one country in consumption and the other in production. That is not free trade.

Bonds vs. gold

The point is that we do not and have not had free trade for most of the period since we left Bretton Woods back in the early 1970s. The U.S. has run an unrelenting string of deficits and the currency has not adjusted. One thing economists never realized was that countries that were loath to run current account deficits and lose gold were not all disturbed by running deficits and having foreigners hold huge amounts of their bonds. A bond is not gold. And apparently the way your 'net asset position' erodes matters more than 'if' it erodes.

Something for the goose, something for the gander

U.S. trade partners have been quite willing to hold U.S. Treasury securities as the U.S. has run larger and larger deficits. And the U.S. has been willing to let them have them. Some in the U.S. have been happy to have an overvalued dollar because it increases U.S. purchasing power and increases U.S. welfare or least it appears to. But foreigners who have helped to prop up the dollar have done so for their own self-serving reasons. They have used their excess dollars from running trade surpluses to plowed them back into the dollar area by buying Treasury securities. As long as they do that with their excess dollars, their currency remains weak and the dollar remains strong and they can continue to drive domestic growth with an export oriented economy.

So this is how we got to where we are today: complacency on the U.S. side and joy at having an overvalued dollar so we can buy stuff cheaply. Foreigners easily fund our fiscal deficit (and other needs) as they need to place their excess dollars in the U.S. to keep the dollar strong and their currency weak to drive their exports to market. But as a result of the too strong dollar, the U.S. becomes uncompetitive and it loses all sorts of jobs to overseas markets. Goods are too cheap and that helps to erode our savings rate.

You pay the piper even if with IOUs

In the end, the U.S. has paid a great cost in competitiveness for this foolishness. There is a generation or more of foreigners who think that keeping an undervalued currency and exporting to the U.S. is a 'birthright.' Meanwhile, the U.S. has run a long period of deficits and used the money it borrowed to fuel consumption not investment. That is a squandering of all the international debt we built up during that period. The consumption goods we bought are gone, but the debt remains. Running a current account deficit is not a bad thing if a country needs to attract savings from overseas for its investment projects. But when it borrows to fuel consumption or to plug holes in domestic finances instead of cutting spending or raising taxes, that is an abuse of those capital inflows. The U.S. is now in a position where it relies on foreign inflows of capital and without them it could not fund the government.

Is the economy really in good shape?

Our economic circumstances are not good. While some laud the stronger growth and complain about Trump strong arming others over free trade, they, in fact, have it backwards. Strong growth obtained through tax cuts while massive deficits loom has only made things worse. Free trade is a way out of this mess, but it will be a slow way out and we will need to develop the labor force to allow us to exploit free trade opportunities. For now our labor force lacks a lot of the necessary skills and it is overpriced.

American firms remain among the most competitive in the world. But they mostly exploit their advantage from operations located in other countries. It will take a lot to lure them back to the U.S. and instead we are moving in the opposite direction with the minimum wage being raised in what is already a high wage economy. There is no doubt that income distribution has been skewed, but fixing this by government fiat sends all the wrong messages. When government must trump the actions of private industry, it sets the stage for that industry to leave and set up shop elsewhere. Simply put, we need to develop a more remunerative structure of jobs.

In an economic system where exchange rates and wages reflect real values, the dollar will be a lot cheaper. That by itself would make U.S. labor somewhat more attractive even though the U.S. labor pool still is largely not up to international skill levels.

It is far from clear how far the push for free trade will go. China is pushing with its belt and road program to continue to dominate world trade and keep things as they are. These are two very different philosophies. China needs to grow more internally, organically. It is too big to expect to use export-led growth since China's exports would have to be massive to do that. Something will have to give.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.