Global| Nov 05 2018

Global| Nov 05 2018U.K. Manufacturing and Services Lose Momentum

Summary

U.K. manufacturing has been losing momentum from late 2017. The services sector has fluctuated in a relatively narrow range since late 2016 with a minor eroding trend. In October, the composite index backtracked to 52.1 from 54.1, a [...]

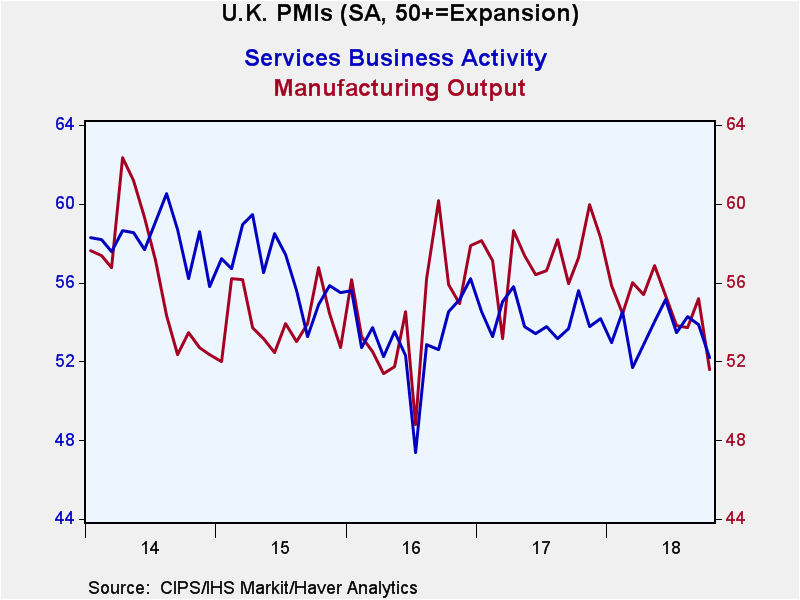

U.K. manufacturing has been losing momentum from late 2017. The services sector has fluctuated in a relatively narrow range since late 2016 with a minor eroding trend.

U.K. manufacturing has been losing momentum from late 2017. The services sector has fluctuated in a relatively narrow range since late 2016 with a minor eroding trend.

In October, the composite index backtracked to 52.1 from 54.1, a two-point drop in one month's time. The composite index most recently peaked at 55.2 in June, it was slightly higher in October 2017 and higher still in April 2017 at 56.2. The services sector has been oscillating or cycling lower for some time. The manufacturing index has had a longer clearer set of cycles. It reached its recent peak in November 2017 at 58.2. Since about February this year, the actual manufacturing index has been tracking closely with its 12-month low or setting new 12-month lows as it has done this month.

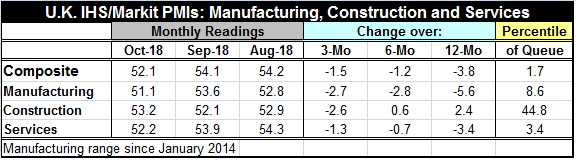

The queue standings are very telling. These standings place each sector in its queue of ordered values since January 2014. On this basis, construction is the sector closest to ‘normal' as it has a 44.8 percentile standing which is only modestly below its median value which occurs at a queue value of 50 (by construction) for queue standings. Manufacturing has fallen sharply and it reaches its lower 8.6 percentile of its historic queue of data. Services that have eroded slowly in an oscillating fashion have been lower on this timeline only 3.4% of the time. Note that the services' raw diffusion reading is higher than manufacturing's diffusion reading but that the service sector queue standing is lower. Diffusion indexes have different tendencies in different sectors. The queue standings provide a relative assessment; an assessment of each sector using its own history of information. On this timeline back to 2014, manufacturing averages a PMI reading of 53.9, compared to a higher average of 55.2 for services.

The composite index is a weighted average of the manufacturing and services indexes and - interestingly- despite its status as an ‘average' its queue standing is weaker than either of its components taken in isolation. This lower composite standing is another feature of the U.K. slowdown that both major sectors are unusually weak at the same time. In the past, when one sector was ‘this weak' the other was relatively stronger. Now with Brexit in play, both sectors are responding to the same environment, stimulus and risk factors and that has led the economy to weaken with greater synchronization and depth. This makes the BOE's job easier in that both sectors emit the same signal so there is less policy confusion about what to do. But it makes the BOE's job harder since it has to work against two sectors' momentum when the real economy goes off track.

The relatively stronger construction index still is hampered since investment has been held back as firms have continued to ponder what the Post-Brexit situation will look like.

The recent reports on Brexit negotiations suggest that that there is much more of a meeting on the minds on issues and a plan to deal with the Irish border. But Brexit watchers are too savvy to be taken in by this since nothing is really done until both sides declare it and until a deal is actually signed. On the U.K. side, it is not just Theresa May who must cut a deal with the EU negotiator, but she then must sell it for approval back home as well.

The Bank of England has said that it stands ready to react and make the policy that the U.K. needs depending on its Brexit circumstances. For now the economic background shows weakening growth. And while inflation is over the BOE target, it also broke sharply lower in September making the overshoot look like it is less in need of attention. But the main point about the BOE is that it is all–in without dogma and actively handicapping the economy's needs. Those needs remain unclear. Growth and inflation trends at the moment seem to nudge monetary policy in slightly different directions, but the Brexit path and circumstances still have not been made clear.

Robert Brusca

AuthorMore in Author Profile »Robert A. Brusca is Chief Economist of Fact and Opinion Economics, a consulting firm he founded in Manhattan. He has been an economist on Wall Street for over 25 years. He has visited central banking and large institutional clients in over 30 countries in his career as an economist. Mr. Brusca was a Divisional Research Chief at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY (Chief of the International Financial markets Division), a Fed Watcher at Irving Trust and Chief Economist at Nikko Securities International. He is widely quoted and appears in various media. Mr. Brusca holds an MA and Ph.D. in economics from Michigan State University and a BA in Economics from the University of Michigan. His research pursues his strong interests in non aligned policy economics as well as international economics. FAO Economics’ research targets investors to assist them in making better investment decisions in stocks, bonds and in a variety of international assets. The company does not manage money and has no conflicts in giving economic advice.

More Economy in Brief

Global| Feb 05 2026

Global| Feb 05 2026Charts of the Week: Balanced Policy, Resilient Data and AI Narratives

by:Andrew Cates