- Consumer spending and business investment in structures accounted for most of the adjustment.

- Although growth was slow, the results were not alarming.

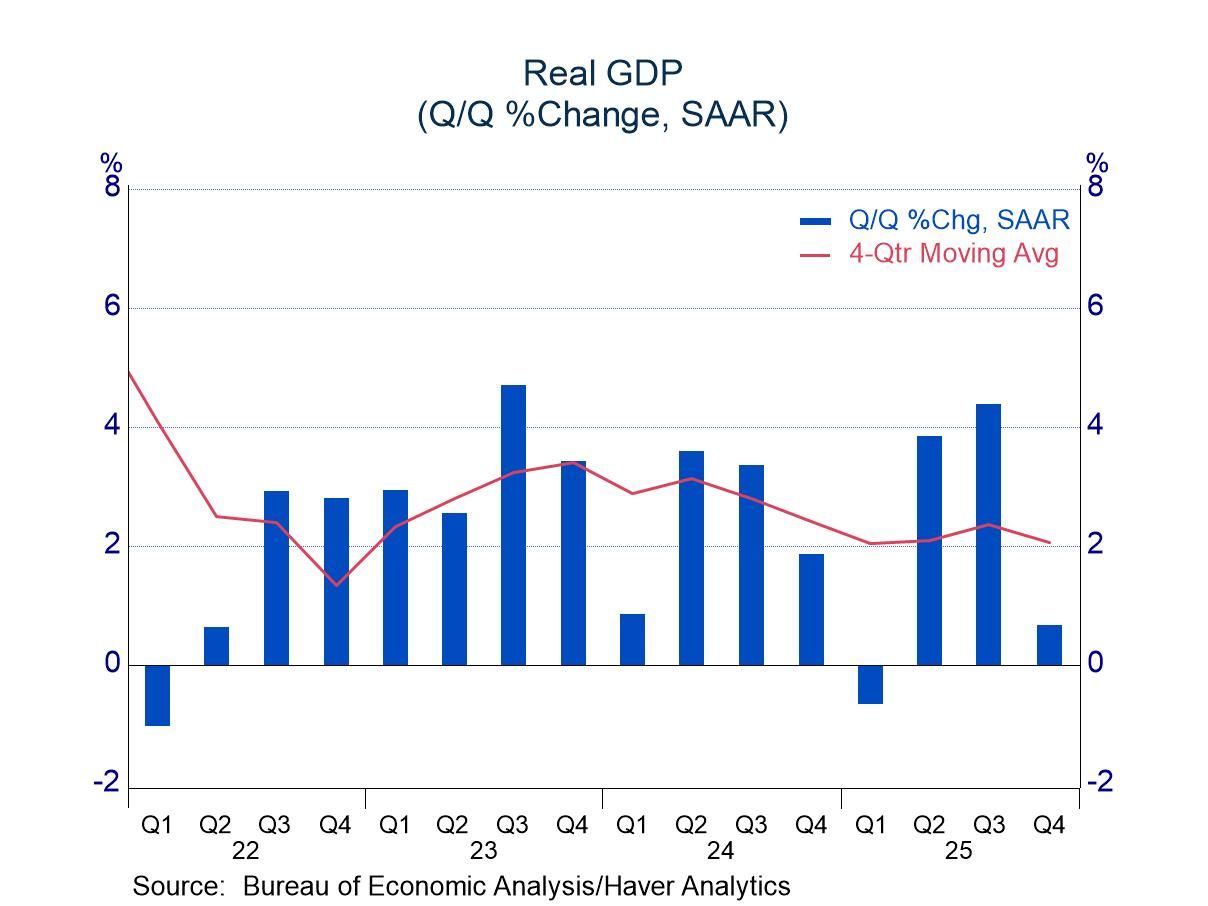

Revised Q4 GDP: Downward Adjustment Leaves Modest Growth

More Commentaries

- USA| Mar 12 2026

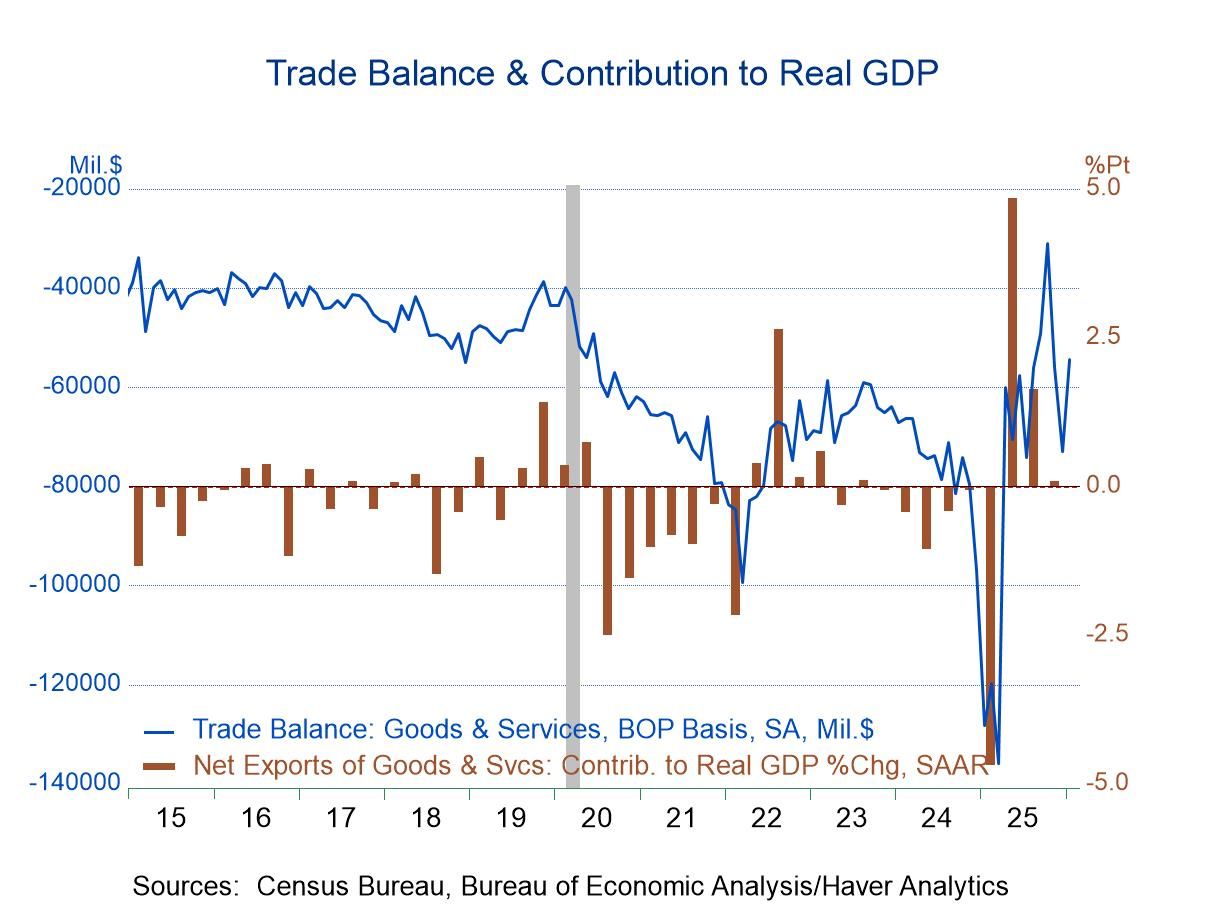

U.S. Trade Deficit Narrowed More than Expected in January

- The deficit in goods and services narrowed to $54.5 billion in January from $72.9 billion in December

- Exports rebounded, rising 5.5% m/m in January after a 1.6% m/m decline in December.

- However, 60% of the exported goods rebound was in nonmonetary gold and other precious metals.

- Imports edged down 0.7% m/m following a 3.5% monthly jump in December.

- The goods deficit narrowed to $81.8 billion while the services surplus widened slightly to $27.3 billion.

by:Sandy Batten

|in:Economy in Brief

- USA| Mar 12 2026

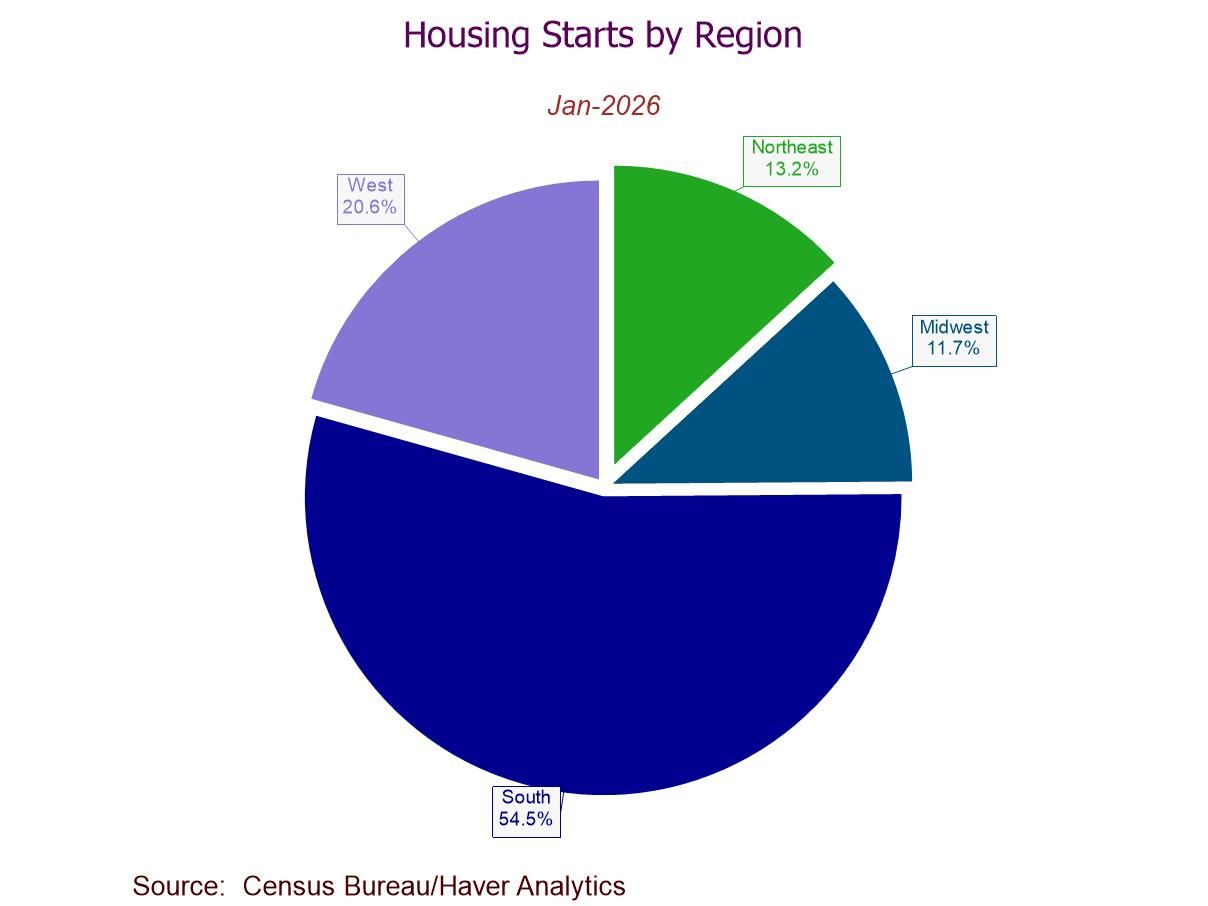

U.S. Housing Starts Jump in January to an 11-Month High

- Housing starts +7.2% (+9.5% y/y) to 1.487 mil. in Jan.; largest of three straight m/m gains.

- Multi-family starts at highest level since May ’23; single-family starts down for the first time in four mths.

- Starts m/m up in the Northeast (+47.4%) and South (+11.4%), but down in the Midwest (-10.8%) and West (-7.5%).

- Building permits at a five-month low, w/ declines in both single-family and multi-family permits.

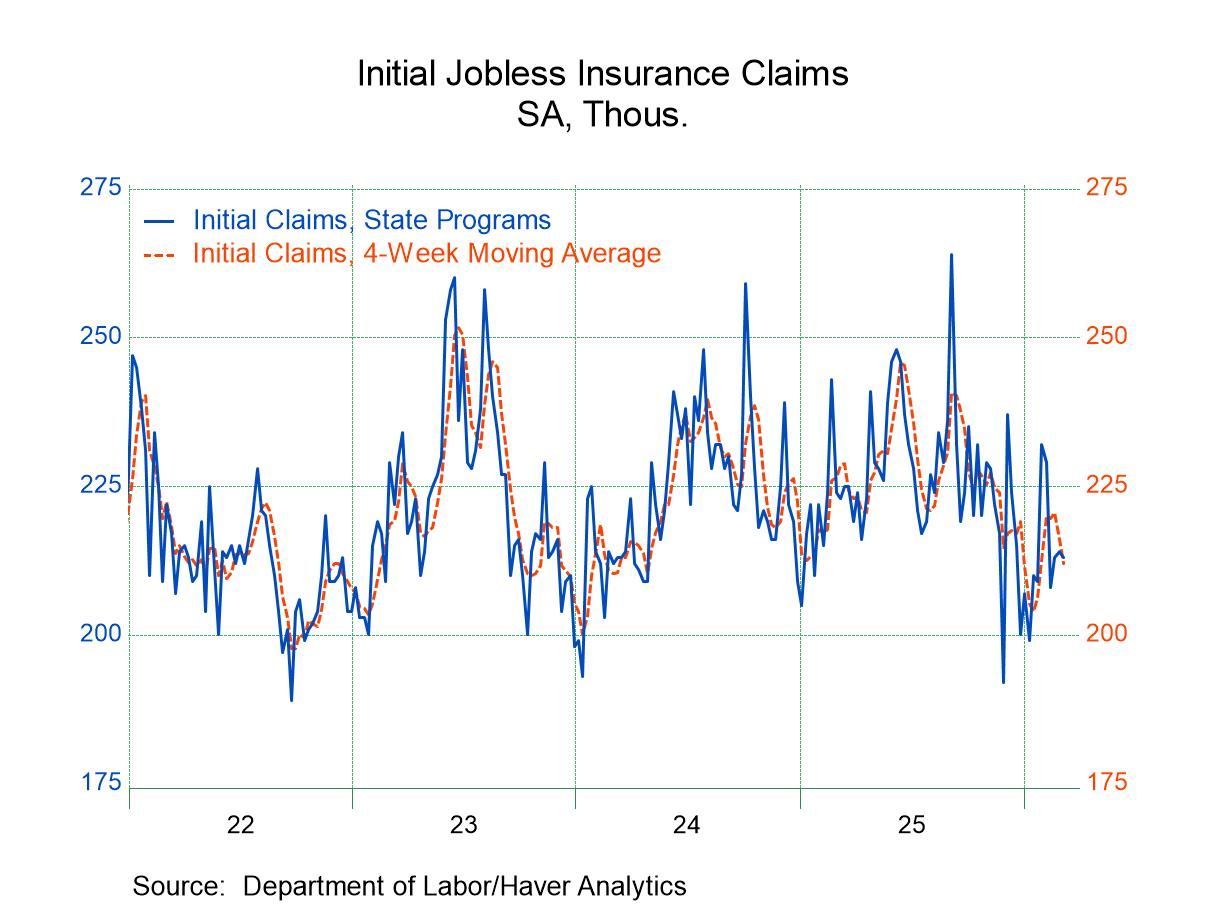

- New claims dipped by 1,000 to 213,000.

- Continuing claims declined by 21,000 to 1.850 million.

- The insured unemployment rate remained at 1.2%.

- Japan| Mar 12 2026

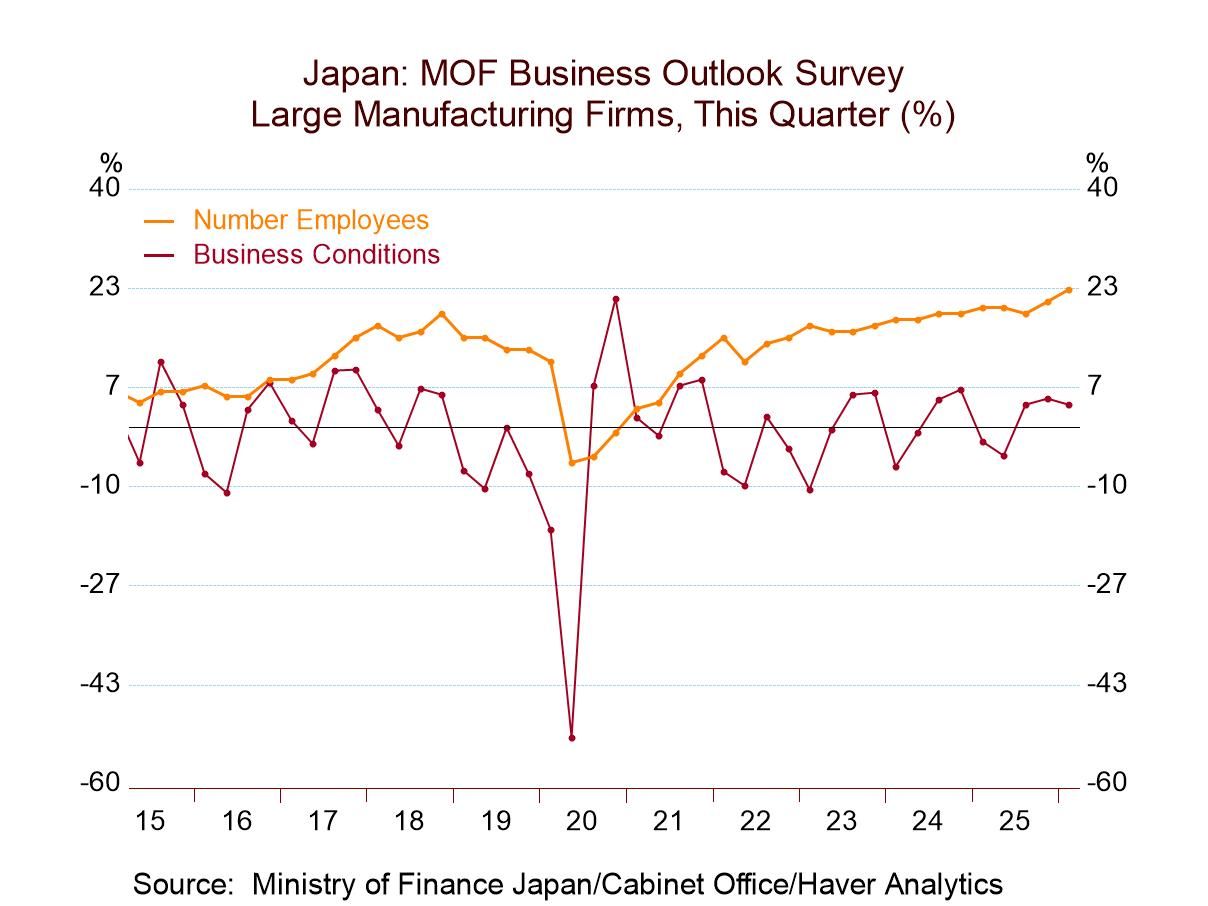

MOF Japan Business Outlook Survey

Japan's Ministry of Finance business outlook survey shows a slow but positive improvement in the outlook for employment among large firms, while the outlook for large manufacturing firms’ hiring continues to cycle and oscillate around zero (see Chart).

The assessment on current observations of the economy slipped to +4.4 for all large enterprises in the first quarter of 2026, compared to +4.9 in the fourth quarter of last year. For large manufacturing enterprises, the assessment slipped to 3.8 from 4.7. There were also slippages reported for medium-sized enterprises as well as for small enterprises; for both the total and manufacturing sectors, assessments were worse, the smaller the reporting unit (on both a net reading basis and a percentile standing basis).

The quarter-ahead assessment slipped to 3.7 from the 4.4 assessment of the first quarter for all large enterprises. For large manufacturing enterprises, the outlook slipped from plus 3.8 in the first quarter of this year to -1.1. The second quarter ahead outlook, however, improved to 4.7 from 3.7 for all large enterprises, and the manufacturing outlook for two quarters ahead picked up to 3.3 from -1.1 in the quarter ahead. However, that 3.3 outlook for large manufacturing enterprises is still below the first quarter assessment (of 3.8) as well as below the fourth quarter and the third quarter assessments of 2025.

The percentile standing of the quarter-ahead assessment for all large enterprises is 44.6. For manufacturing firms, the percentile standing is 38.4, and for nonmanufacturers it is 62.2. The percentile standing values compare the current observation with a history of observation readings back to 2007; values above the 50th percentile are above their historic medians. We can see for the quarter ahead for large enterprises all of their responses are above their medians, and the relative strength resides among nonmanufacturing enterprises; they report the highest standings.

For the second quarter ahead, the percentile standings slip for the total group of large enterprises as well as for manufacturing and nonmanufacturing, separately. This occurs even though the net assessments improve from the quarter ahead to two quarters ahead. You can get an inkling ‘why’ by looking at the ‘average’ and noting that the average two-quarter ahead reading has been higher than the average quarter-ahead reading. So, to rank higher than the quarter-ahead, the second-quarter ahead has a higher hurdle to go over. The standing for nonmanufacturing slips from a 62.2 percentile for the quarter ahead to a 58.1 percentile standing for the second quarter ahead. Large manufacturers take a relatively large step back to a 28.4 percentile standing two quarters ahead from the 38.4 percentile for one quarter ahead. These step backs are reflected in the headline which steps back to 37.8 for two quarters ahead from a 44.6 percentile standing for the first quarter ahead.

What is evident in this survey is that large enterprises that the MOF surveys are becoming increasingly pessimistic as we look farther into the future, since the current rankings for all large enterprises, large enterprise manufacturers, and large nonmanufacturers show the strongest percentile standings among this triad of readings for the current quarter, with the quarter-ahead standings weaker and two-quarter-ahead standings weaker still. This growing pessimism is not a good feature.

Medium and small enterprises not as dismally inclined Medium-sized firms: The transit to greater pessimism that we see for large enterprises as we look further into the future does not carry over to medium enterprises. Medium enterprises do see lower readings for the quarter ahead compared to the current-quarter assessments, and generally the quarter ahead provides assessments that are below the 50% mark, making them below median expectations as well. However, for two quarters ahead, the percentile standings improve, and at least for medium-sized manufacturing enterprises, there is a reading above the 50-percentile mark for that category two-quarters ahead, putting it even above the 45.2 percentile reading posted for the current quarter.

Small firms: For small enterprises, there is no real generalization across the various types of firms. Manufacturing firms’ percentile standing from the current quarter to the quarter ahead just about halve themselves, a sharp step back for manufacturers. However, for nonmanufacturers, there's an improvement from a 56.2 percentile standing in the current quarter to a 60.3 percentile standing in the quarter ahead. These two groups are moving in opposite directions for two quarters ahead. Manufacturers stop that deterioration and gain back just a small measure of what they lose in the quarter ahead with their two-quarter ahead standing, while nonmanufacturers lose some of their ebullience as the percentile standing drops to a 50.7 percentile reading from 60.3 but still sports an above-median value.

Global| Mar 11 2026

Global| Mar 11 2026Charts of the Week: Geopolitics Meets the Global Economy

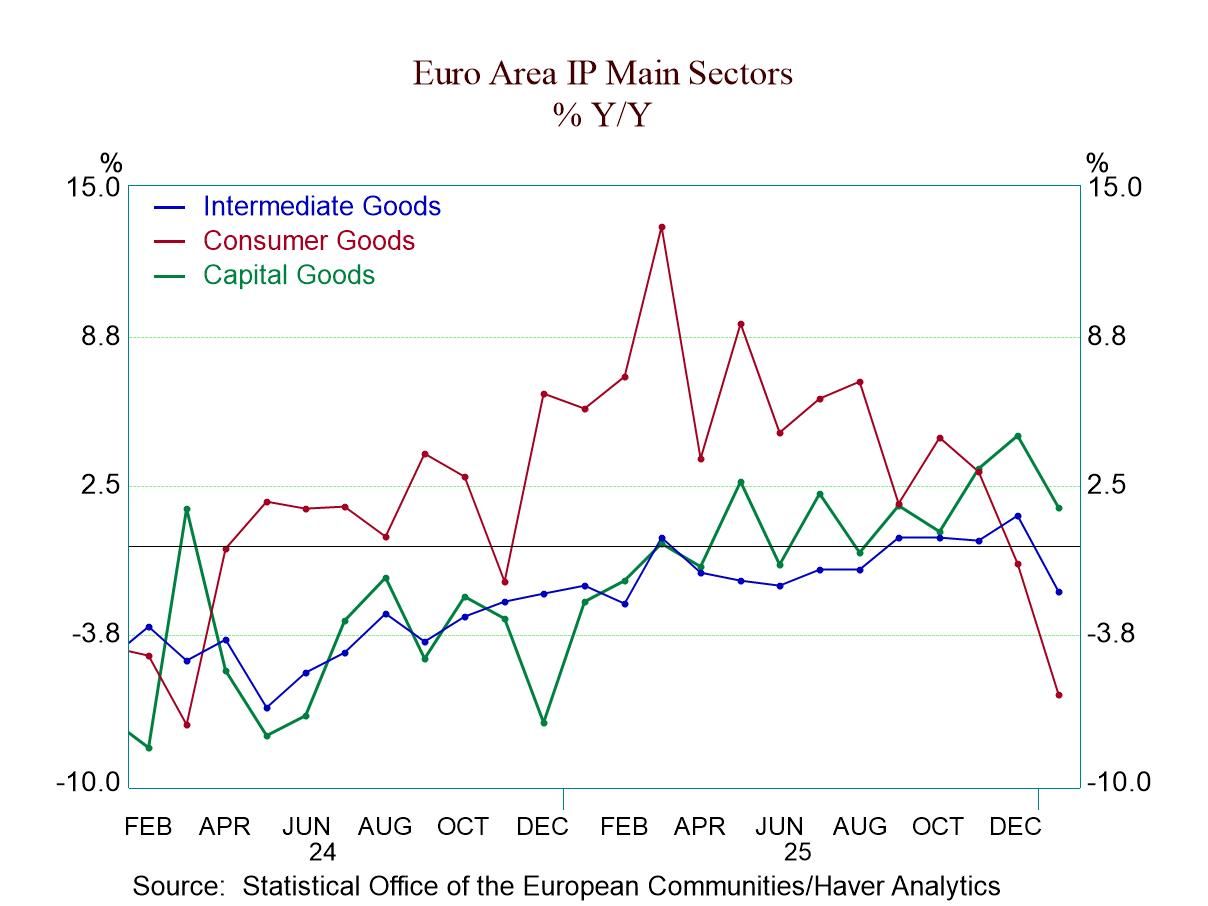

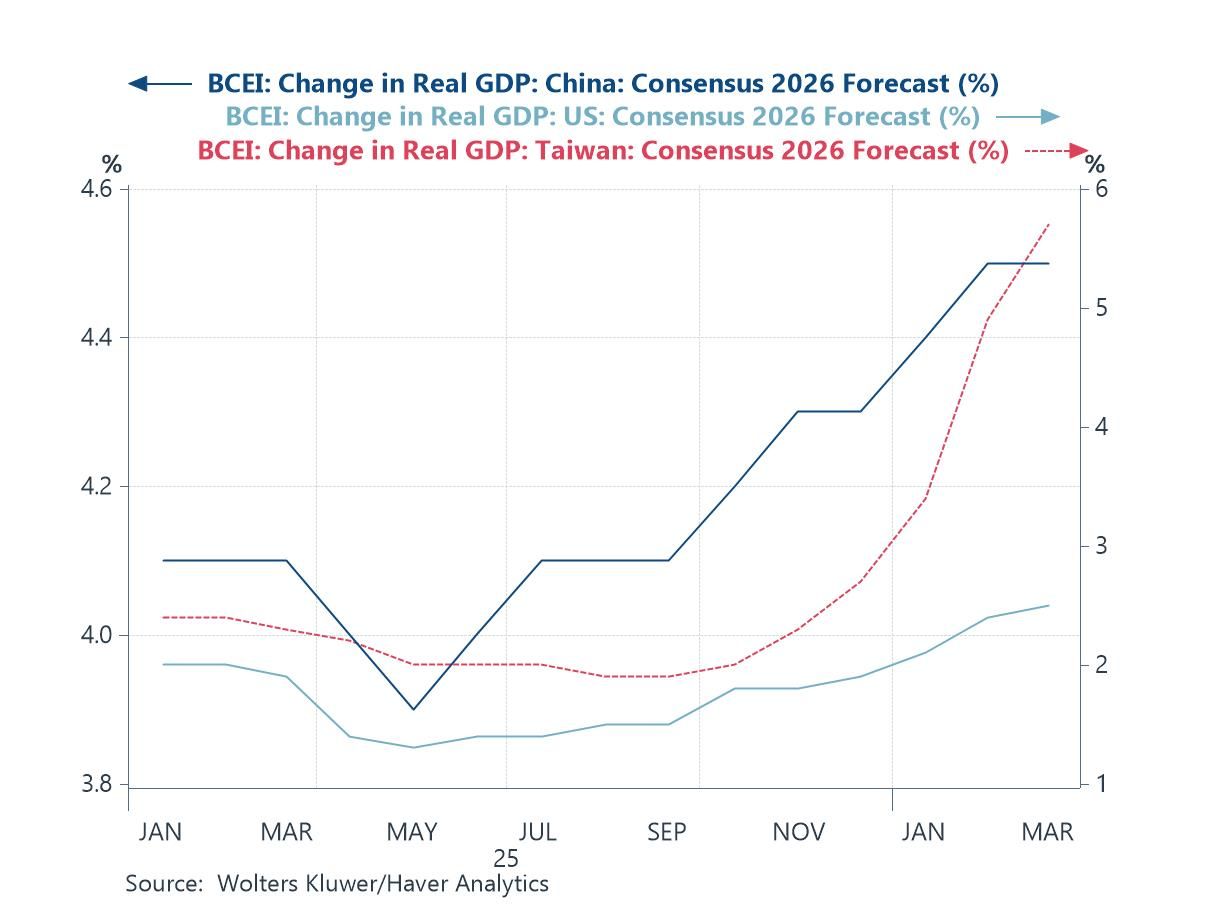

The past few days have seen financial markets rattled by a sharp escalation of tensions in the Middle East, with oil prices rising, risk assets wobbling and investors reassessing the potential macroeconomic fallout from a possible energy shock. Yet, taken together, this week’s charts suggest that the global economic outlook has so far remained relatively resilient. Blue Chip consensus forecasts for 2026 growth have held steady in recent months, with Taiwan’s steadily improving outlook hinting at the ongoing influence of the global AI investment cycle. That said, forward-looking sentiment indicators are beginning to show some cracks: the latest Sentix expectations index registered a sharp deterioration in March, potentially reflecting rising geopolitical uncertainty. Inflation expectations, by contrast, have shifted only modestly, with forecasters making few meaningful revisions despite the recent surge in oil prices. Financial markets appear to share that view, as movements in two-year US Treasury yields—often a proxy for expectations of Federal Reserve policy—have not mirrored the sharp rise in crude prices, suggesting investors currently see the oil shock as temporary. The final charts highlight why energy markets nonetheless remain central to the outlook: many major economies remain significant net oil importers, and in much of Asia oil price movements feed quickly into consumer energy inflation. Should geopolitical tensions persist and keep crude prices elevated, these channels could yet transmit broader macroeconomic pressures in the months ahead.

by:Andrew Cates

|in:Economy in Brief

- USA| Mar 11 2026

February CPI: Moderate Increase Despite Jumps in Volatile Areas

- Food and energy post above-average price increases.

- Ex food and energy, apparel and airfares misbehave...

- ...but most other areas showed modest price changes.

- USA| Mar 11 2026

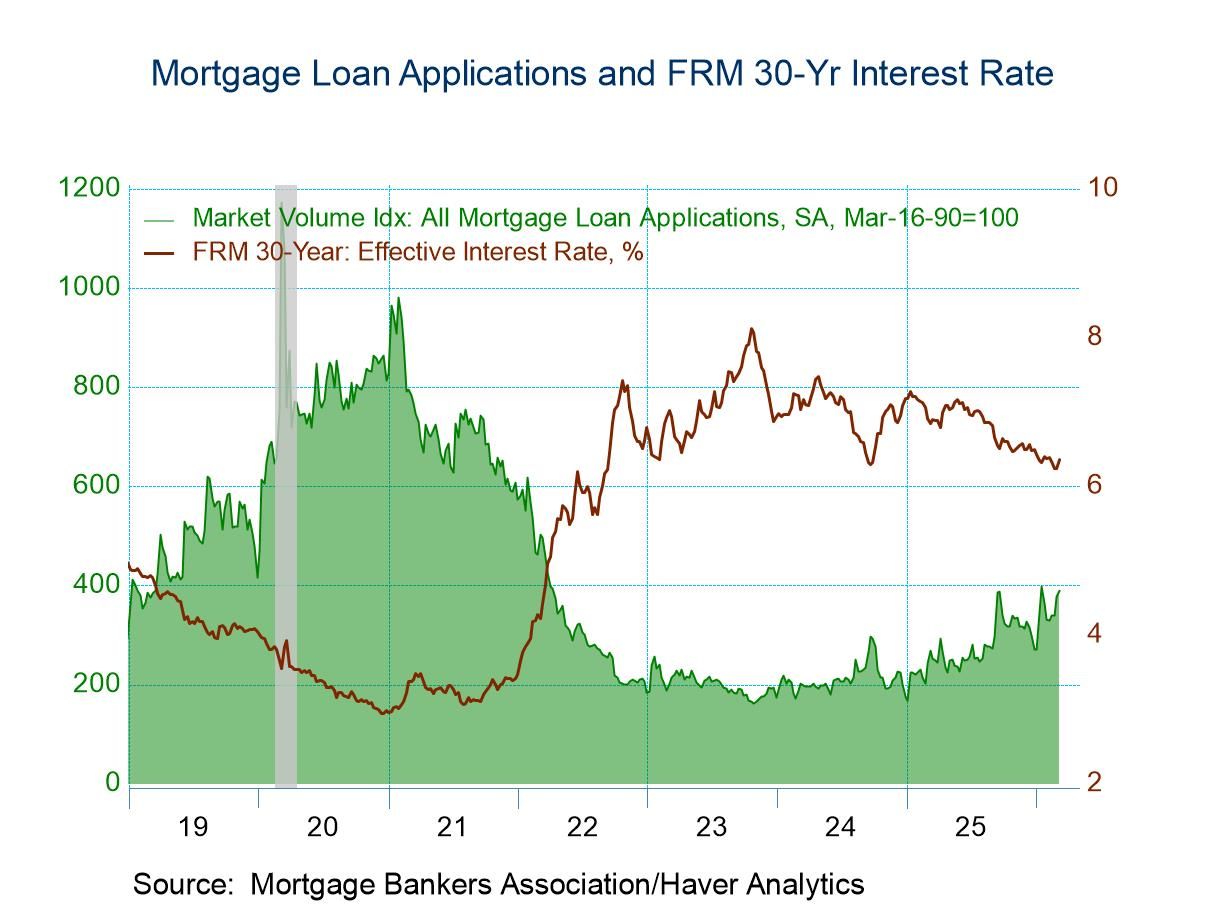

U.S. Mortgage Applications Rose Again in the March 6 Week

- Both applications for loans to purchase and for loan refinancing rose.

- Effective interest rate on 30-year fixed loans rose 12bps to 6.36%.

- Average loan size declined.

- Japan| Mar 11 2026

Japan Indicators: Strong Economy—Still, Large Question Marks

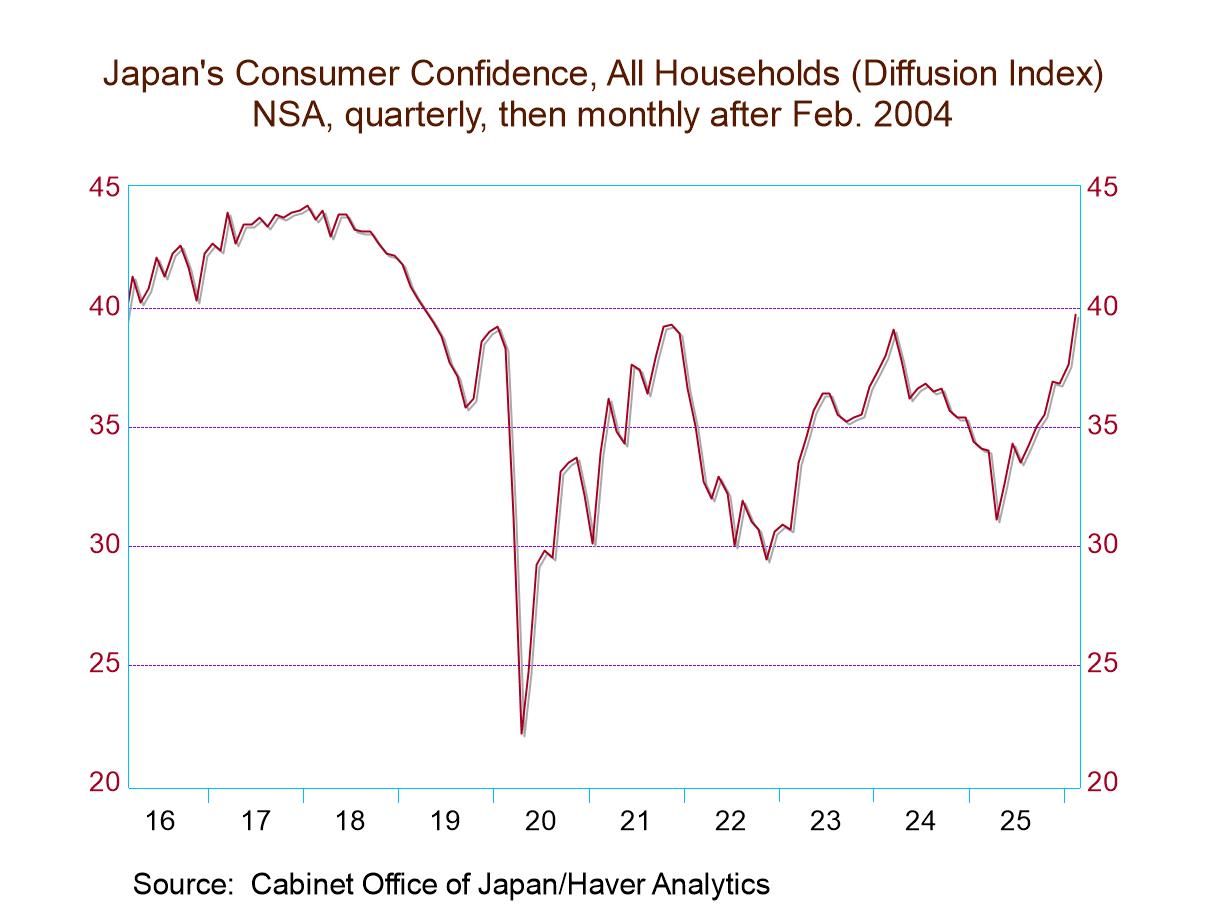

Japan's economy may not be firing on all cylinders, but the economy is looking pretty firm, and consumer confidence is just pushing up through an area that has defined several of its post-COVID peaks. Inflation in Japan is uncomfortable. The PPI index rose 0.2% in January and is running at 2.4% year-over-year. The headline CPI for January declined by 0.1% and is running at a 2.4% annual rate, above the Bank of Japan’s preferred target. However, it only has a 61.7 percentile standing compared to a 71.7 percentile standing for the PPI—above its median but not terribly high on data back to 2006.

Retail sales: Key Japan activity variables are showing sustained expansion. Retail sales in January rose by a sharp 4.6%. The sequential growth rate for retail sales mushrooms from a 1.9% pace over 12 months to a 7.3% pace over six months to 15.8% pace over three months. That’s very solid and extremely strong.

Exports: But with the yen weak on global exchange markets, Japan's exports rose by 9.9% in January. The sequential growth rate for exports is 16% over 12 months, which jumps to a 38.7% pace over six months and then jumps again to a 67.8% annual rate over three months. These are stunningly strong figures.

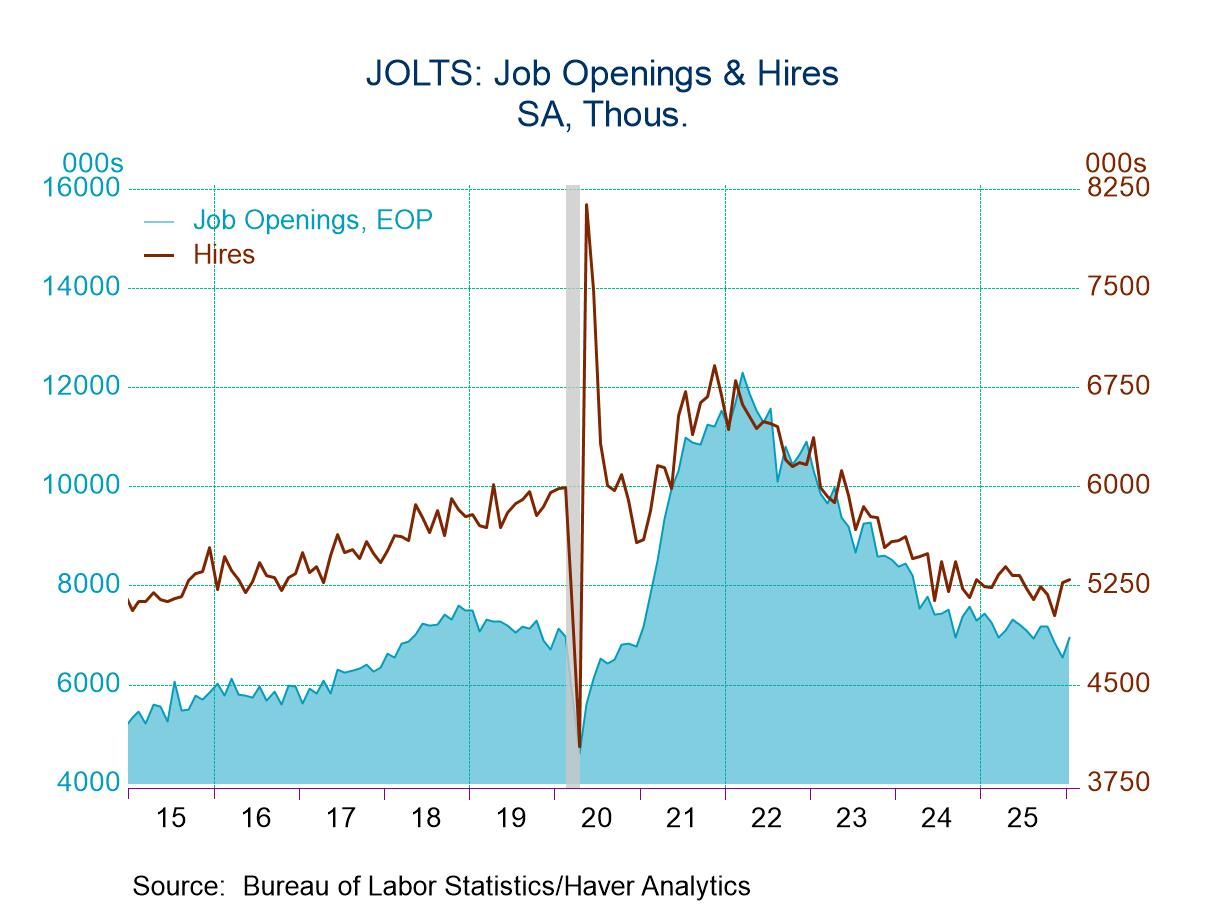

Jobs: Employment in Japan continues to show month-to-month gains, but the gains are not historically strong, even though the sequential performance is sound at 0.5% growth over 12 months and picking up to 0.6% at an annual rate over three months. That’s not bad for a country with fading demographics. However, the standing for employment is only at its 45th percentile, putting it below its median, which occurs at a ranking of 50%. On the other hand, the ranking is not far below its median, with its 45.3 percentile standing.

LEI: Japan's leading economic index rose by 1.9% in January, accelerating from its December increase of 0.6%. Again, the sequential growth rates for the LEI are strong and hint at acceleration, with a 2.5% gain over 12 months, a 9.9% annual rate gain over six months, a pace that is nearly maintained over three months, where the growth rate comes in at a nearly identical 9.2%.

Surveys: The LEI, viewed as a level, is showing ongoing gains and has a historic standing that is near its historic median. The economy watchers index has weakened in the past few months, but the sequential averages show ongoing upward momentum and a historic ranking above its median at a standing in its 52nd percentile.

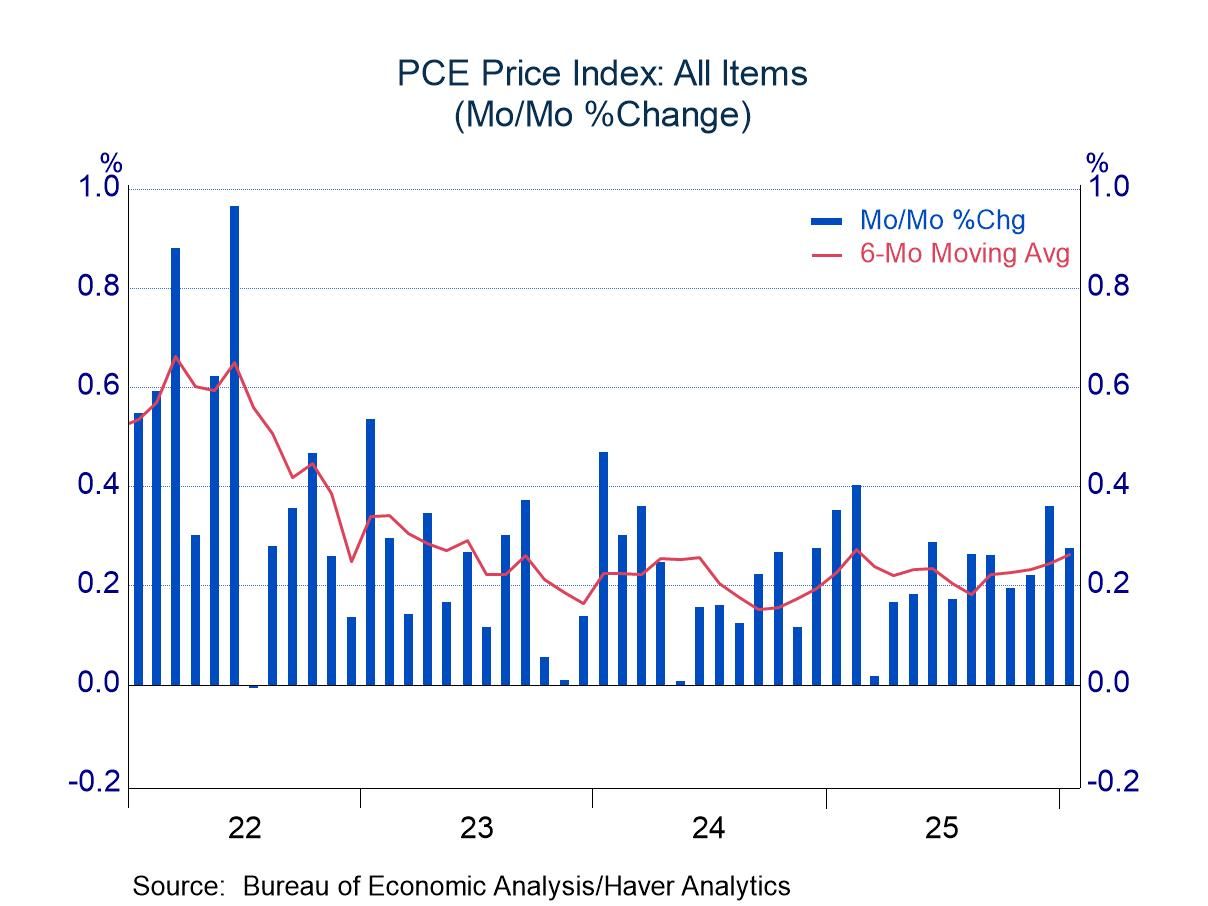

Inflation: The inflation numbers are the ‘fly in the ointment’ for Japan, although neither the PPI nor the CPI headline (headline excluding fresh food) shows a tendency - a strong tendency - to accelerate. However, there's a war in the Middle East. Oil prices are going up, and that’s going to hit Japan hard — and it’s going to have an inflation effect.

What will central bankers do? One of the key questions moving forward is how central banks are going to deal with the inflation effects from oil, because while it clearly gives a supply shock, it's a relatively large one and nobody is sure how long-lived it's going to be and how much of this supply shock will get into the core inflation measures beyond just the headline.

- of2702Go to 1 page