Geopolitical tensions in the Middle East have escalated sharply following joint air strikes by Israel and the United States on strategic targets in Iran. While the ultimate trajectory of the conflict remains highly uncertain, the episode highlights the potential for geopolitical shocks to ripple through multiple channels of the global economy—from energy markets and shipping routes to supply chains, inflation dynamics and monetary policy. In this week’s Charts of the Week, we present six charts that illustrate some of the key issues, implications and points to watch, including movements in geopolitical risk (chart 1), shipping activity through the Strait of Hormuz (chart 2), energy prices (chart 3), global supply chain pressures (chart 4), inflation surprises (chart 5) and the evolving structure of global electricity generation (chart 6). Together they provide a framework for thinking about how events in the region could shape the outlook for the world economy in the months ahead.

- USA| Mar 04 2026

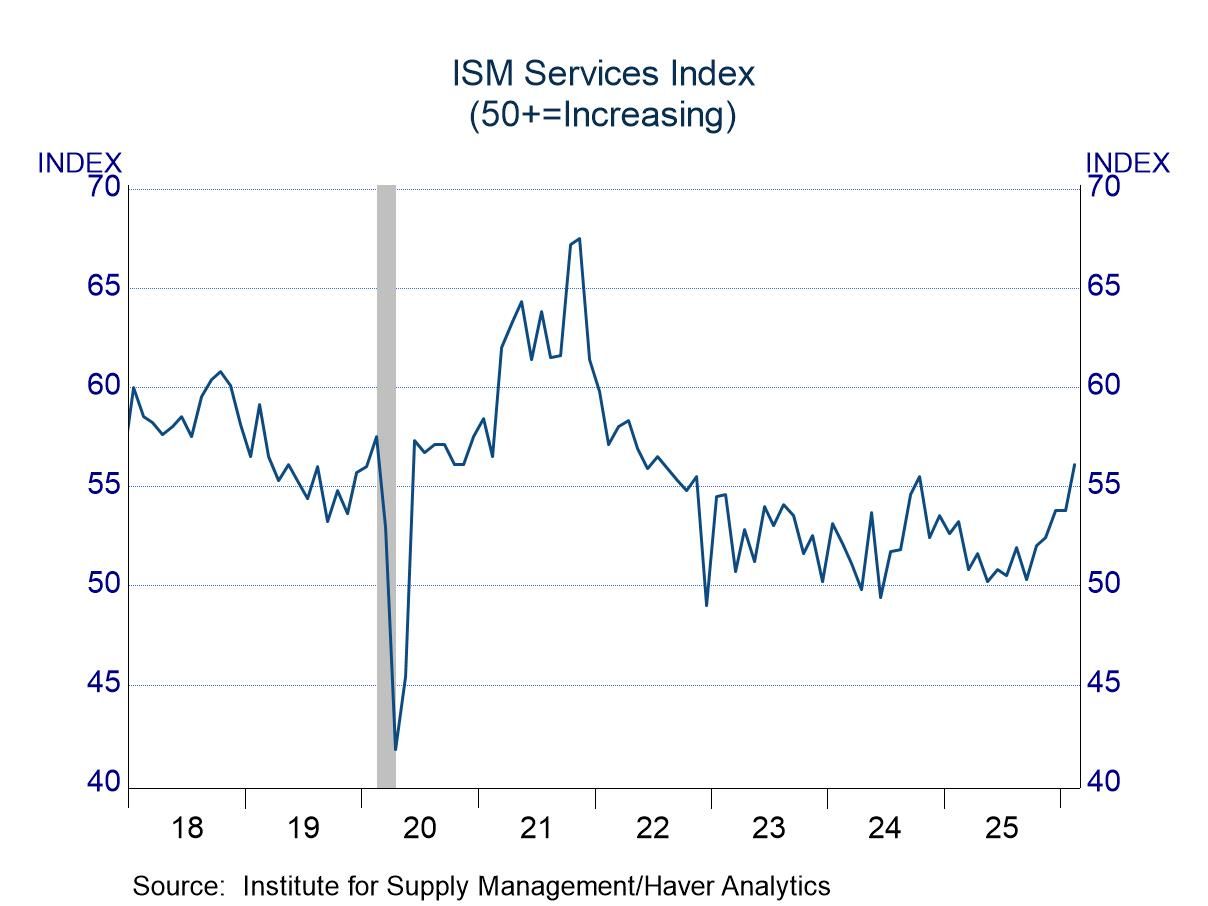

ISM Services: Favorable News from Every Perspective

- Headline index for February jumped to a multi-year high.

- Three of the four components contributed positively.

- The prices index, although still elevated, eased.

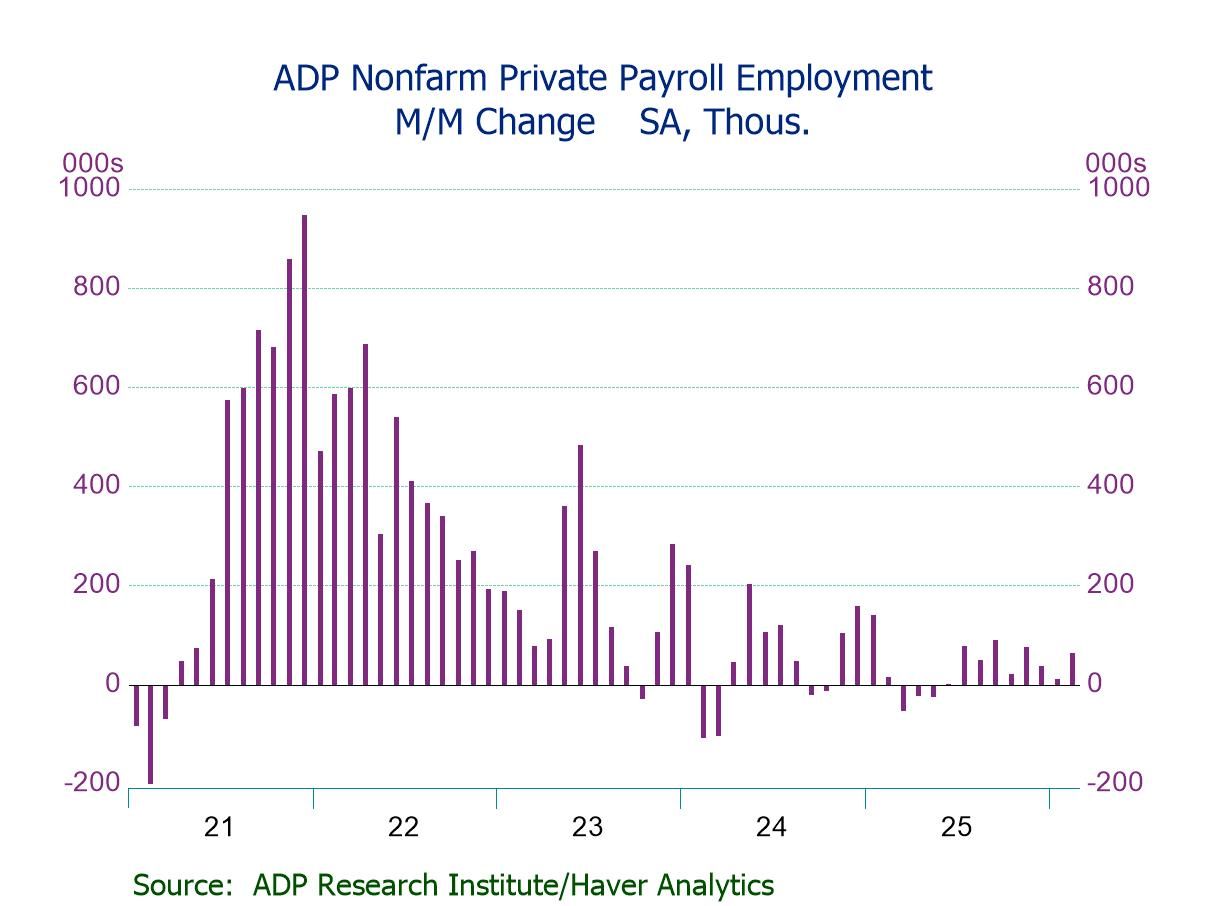

- Private payrolls +63K, eighth straight m/m gain and largest in three months.

- Hiring increase is driven by small businesses (+60K, strongest in four months).

- Service-sector jobs up (+47K), led by education & health svs. (+58K) and information (+11K).

- Goods-producing jobs up (+16K), driven by construction (+19K).

- Wage growth eases y/y for job changers (6.3%) but steady for job stayers (4.5%).

Global| Mar 04 2026

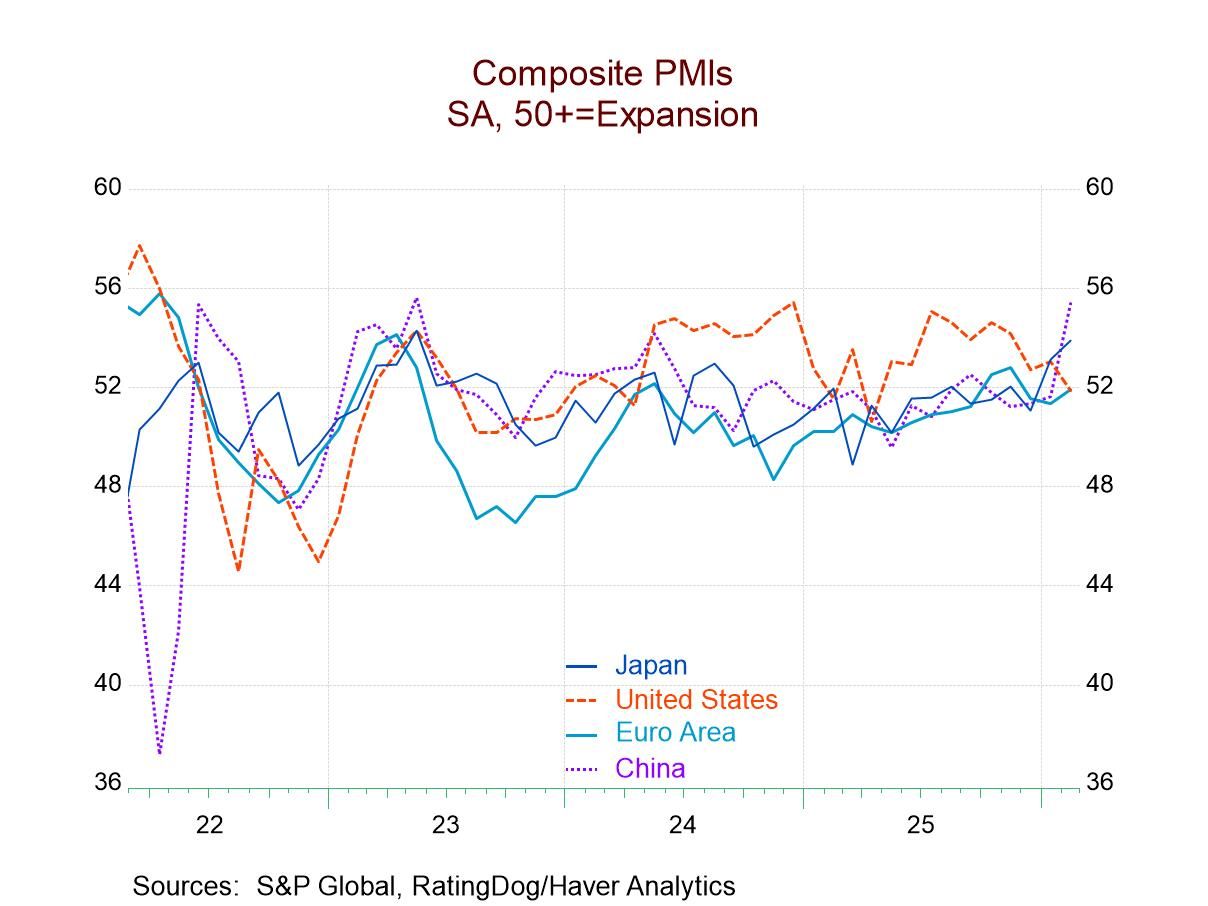

Global| Mar 04 2026S&P Composite PMIs Show Recovery Progresses

The composite PMIs showed modest increases on their full sample average and a modest step-back in the full sample median calculation in February. However, the number of areas below 50 fell to 4 in February; that count was only 5 in January, and there were none showing declines in December, so there's a great sense of progress in place. The proportion of reporters in February that were getting worse was only 40%, compared to 44% in January and 76% in December. So there has been a change for the better in terms of the proportion of these 25 reporters who are registering better growth month to month in the last two months, in particular.

Global| Mar 03 2026

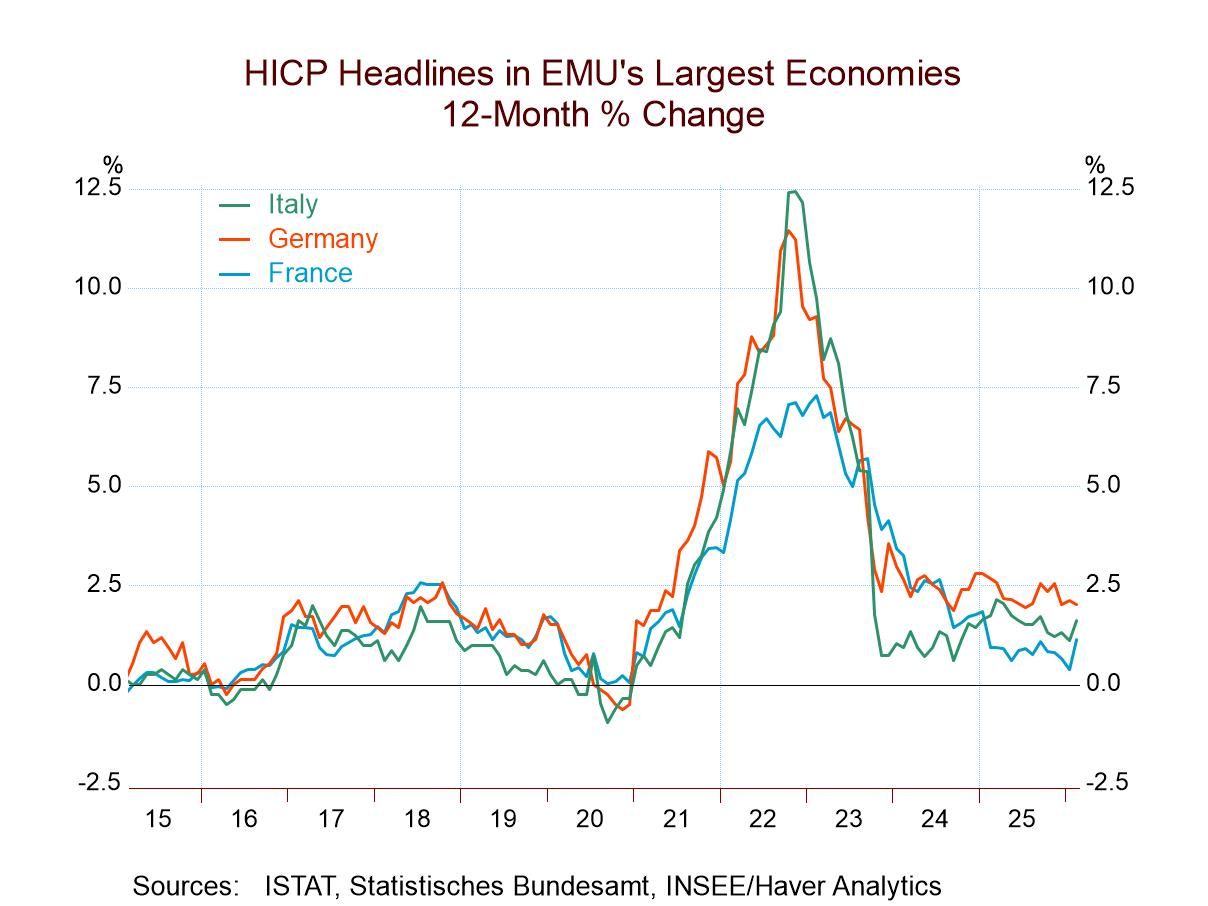

Global| Mar 03 2026Inflation in Europe Picks Up – Ahead of Hostilities

Inflation in the European Monetary Union picked up in February, ahead of the beginning of new hostilities in the Middle East. The increase in the harmonized index of consumer prices moved up to 0.3% in February from 0.1% to January. Progression on the annual rate of price increase moved up to 1.9% over 12 months, to a 2.1% annual rate over six months, and to a 2.4% annual rate over three months.

This is a modest acceleration and not something to get particularly excited about, except that with new hostilities in the Middle East, oil prices have begun to rise significantly, and there will be apprehension about how much more there is to come. However, the initial oil price reaction was muted, and the follow-up price reaction has also been relatively muted so these will translate into a nontrivial impact on inflation and in the harmonized index for consumer prices in the monetary union, as well as in the key prices watched by central banks globally.

Big Four Economies The Big Four economies in the monetary union produced scattered results in February. Germany produced no increase in its February HICP. The HICP for France jumped by 0.4% month-to-month. Spain showed an increase of 0.2%; Italy reported an outsized increase of 0.7% in February. Still, the January and February data for this group of countries show prices mostly very well behaved. If we simply multiply these 12 increases (four countries over three months) together we get prices rising at a 2.2% annual rate across all the countries over the three months. That is close to target.

Annual and Sequential Big Four Inflation Inflation for the Big Four economies ranges from a top pace of 2.4% in Spain to the lowest pace of 1.1% in France with Italy's 1.6% and Germany's on-target 2% making up middle cases. Even the biggest price increase from Spain at 2.4% is not particularly frightening. Inside of 12 months looking at the six- and 3-month trends, Germany's trends move up to 2.6% over six months and then down to 1.2%. France's 6-month inflation remains at 1.1% over six months but then moves up to a 1.9% annual rate over three months. Italy's 12-month pace of 1.6% holds in place over six months, but then the 3-month inflation rate jumps to a 4.1% annual rate. For Spain, the 2.4% 12 month rate rises to a 3% annual rate over six months and then falls sharply to a 1.6% annual rate over three months.

Headline vs. Core Inflation Headline inflation rates, of course, are mercurial because of the impact of oil prices on them. Two early reporters gave us core inflation or ex-energy inflation rates. In the case of Spain, core inflation is stuck at 2.7% on all horizons. Germany's index excluding energy is at 2.4% over 12 months, but then Germany’s six-month pace falls to 2.2%, and its three-month pace falls again to 1.7%. In the case of Germany, 12-month ex-energy inflation is mildly acceptable, but progressing to the three-month horizon, the inflation rate drops back well into place. For Spain, the 2.7% 12-month inflation rate persists across all horizons and is unacceptably high.

Longer Trends Inflation is generally behaving and riding downtrends in the monetary union, with 12- month inflation generally lower than 12-month inflation was a year ago. That is true for all the major metrics in the table except two. The first exception is France when the 12-month inflation rate is 1.1% compared to 0.9% over 12 months a year ago (still, obviously very well behaved). In the case of Spain, core inflation moves up to 2.7% over 12 months after being at 2.2% just a year ago.

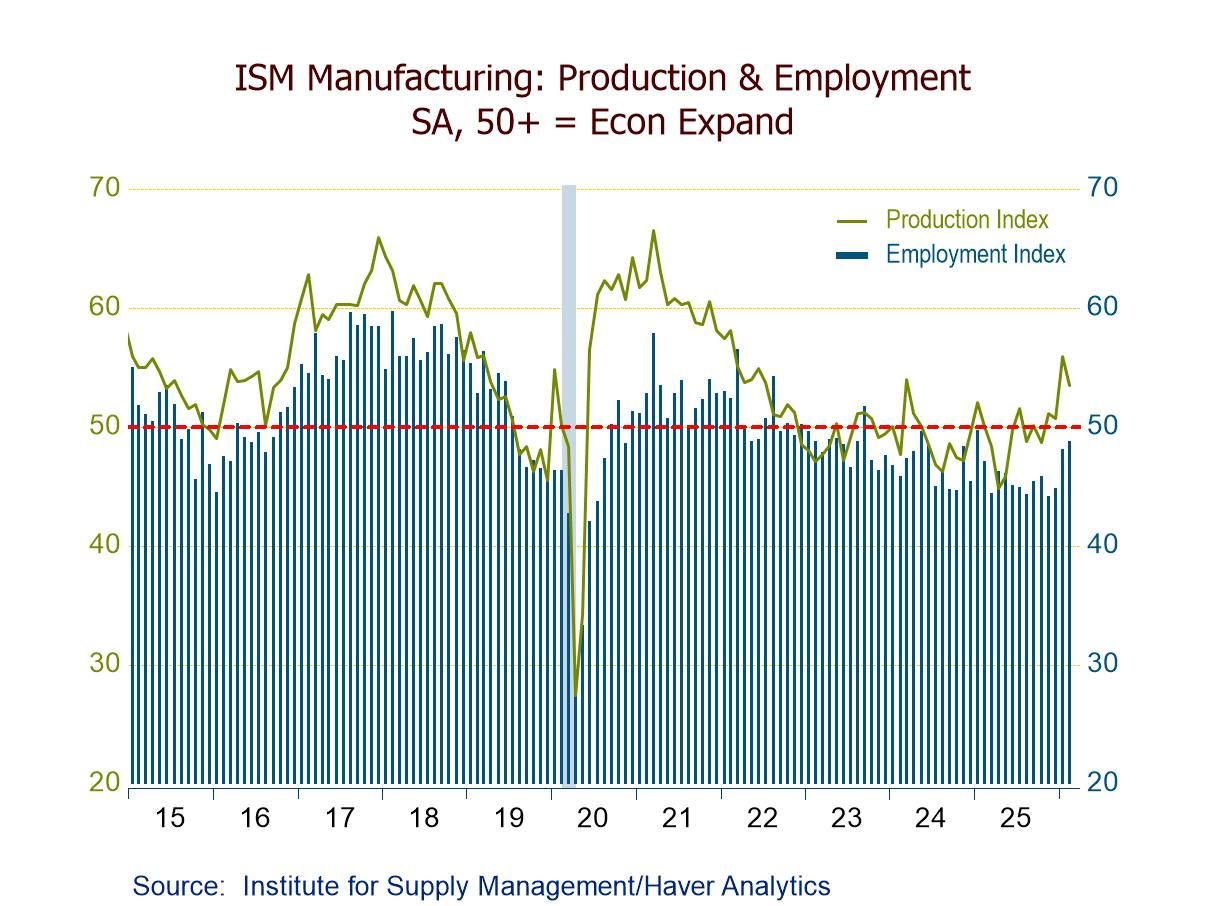

- ISM Mfg. PMI at 52.4 in Feb.; second consecutive month of expansion and only the third in 40 mths.

- Production (53.5) expands for the fourth straight mth.; new orders (55.8) expand for the second successive mth.

- Employment (48.8) contracts for the 29th straight mth. but at the slowest pace since Jan. ’25.

- Prices Index (70.5) hits its highest since June ’22, w/ prices rising for the 17th consecutive mth.

- Exports (50.3) expand for the second straight mth.; imports (54.9) reach the highest level since Feb. ’22.

Global| Mar 02 2026

Global| Mar 02 2026S&P Manufacturing PMIs Show Improvement

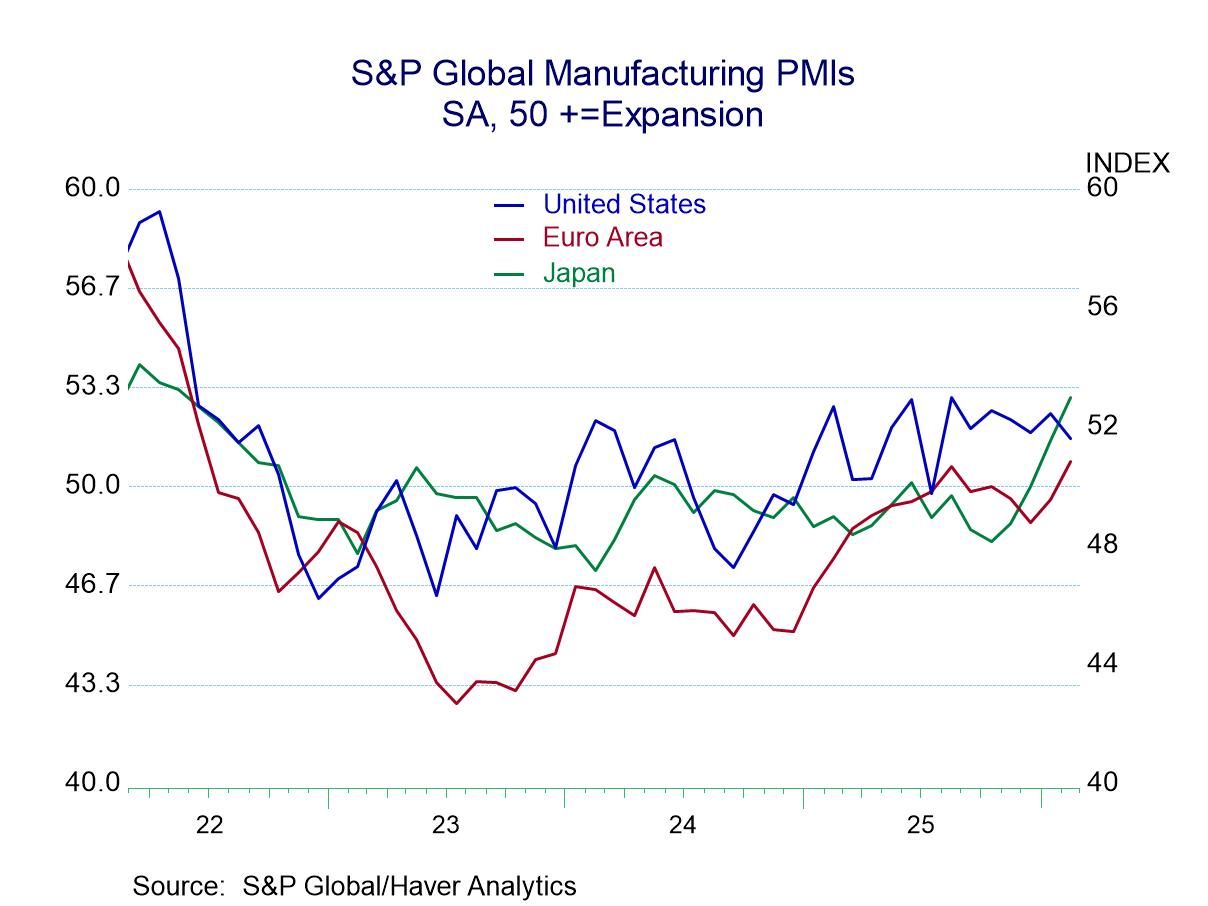

The S&P manufacturing PMI readings for February 2026 continued to show improvement, particularly on a sequential basis.

The chart shows a clear upward tendency for the United States, Japan, and the European Monetary Union where the manufacturing PMIs have been on an increasing track for some time. Japan just surpassed the U.S. this month where the manufacturing PMI reading surged above 50. The U.S. has been steady at that level for a number of months; Japan has just moved up while the euro area reading is starting to show some upward trend.

The table takes the underlying diffusion levels reported by these 18 early reporters and shuffles them into six different cohorts to summarize their performance over different periods.

In February, we see twice as many reporters in the cohort between 55 and 60 as we saw in January; that proportion moved up to 11.1% from 5.6%. The proportion in the 50 to 55 diffusion category (mild improvement) was unchanged at 55.6%; the proportion showing mild below median performance declined to 33.3% in February from 38.9% in January. The other cohorts showed no membership.

If we look at the data grouped into sequential categories of three-months, six-months, and 12-months, we see the neutral to mildly positive category of 50% to 55% moving from 28.2% of total membership over 12 months to 39.8% of membership over 6 months to 55.6% membership over 3 months. This is a clear improvement in performance over this timeline for the category indicating moderate expansion. The stronger expansion category of 55 to 60 shows a membership of 5.6% for all three-time horizons. The category showing weak declines in the 40 to 50 range for diffusion declined steadily from 66.2% over 12 months to 54.6% over 6 months to only 38.9% over 3 months. Over the last three months, fewer than 40% of the reporters were showing mild declines, 55% of the reporters were showing unchanged-to-moderate increases, while relatively larger increases have been posted by 5.6% of the reporters.

Looking back to the right of the table, we can compare the recent 12-month figures to the previous 12-months and to the 12-months before that to get a sense of the smoothed trend. There what we see is the 50 to 55 category three years ago was at 28.2% of the reporting membership; it moved up to 38% of the membership over just a year ago whereas over the past year that membership had slipped to 28% in an environment where tariffs were imposed. Although, as we see from the sequential data, it has over the shorter periods of six months and three months been seeing an increase in membership in that category.

Over the earlier years, there was also stronger membership in the stronger growth category of 55 to 60 percentile. Three years ago, it registered 8.3%, then fell to 6.4% and now sits at 5.6% over the recent 12 months. Over the recent shorter periods of three months and six months, there has yet to be an improvement in that category. As for the weaker category the cohort from 40 to 50%, we see 62% of the membership in that category three years ago, and two years ago that had fallen back to 55.6%, but then over the past year it had moved up to average 66% of the membership: fully 2/3 of the reporting membership over the last year has been in the 40 to 50 the diffusion category though that membership proportion has been falling over the last six and three months.

The grouped statistics show that there is general progress in place and in line with what we see reported in the chart. In addition, we track the number of reporters That are improving period to period. From 12 months to six months to three months, we see that percentage of reporters showing higher diffusion readings steadily improving from 50% to 61.1% to 77.8%. We also track the number of reporters with diffusion below 50 (that is those that are showing contraction) and that number hasn't changed very much; it's at 13 over 12 months and over 6 months while falling only to 12 over 3 months.

However, if we step away from averaging and we look at the raw scores for the last three months, we see the number of countries reporting output that's contracting at 8 in December, at 7 in January and at 6 in February, a clearer sense of progress. Meanwhile, on the monthly timeline, there's also a sense of improvement - not in a monotonic sense – but there is a hint of better general tendency for the percent of reporters that are showing the tendency for higher diffusion to be reported to rise.

The diffusion statistics are up to date, and they basically describe the proportion of the reporters that are seeing activity improve or decline in the reporting area. Diffusion data don’t tell us how strong that improvement is, just whether it's present. Diffusion data tend to be sensitive. They tend to quickly be able to identify changes in trends and right now we're seeing an uptick, an improvement, in the levels of diffusion being reported in this 18-country sample for manufacturing. The results are not decisive, but they are encouraging.

- USA| Feb 27 2026

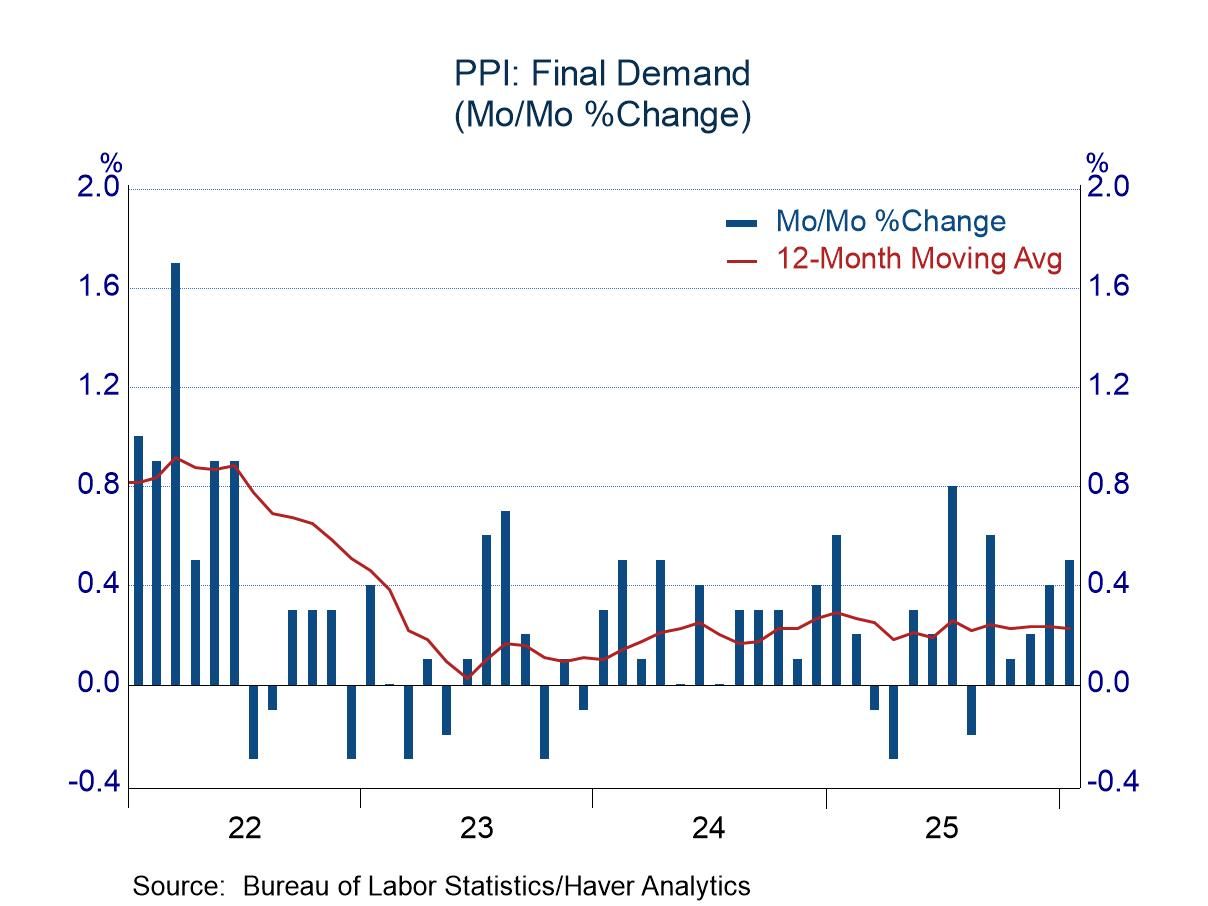

January PPI: Wild Swings in Volatile Areas

- Prices of food and energy fell sharply, while prices of trade services surged.

- Other noisy areas (transportation & warehouse services, construction) posted high-side increases.

- Excluding the (apparently) random shifts, results were tame.

- of2701Go to 2 page