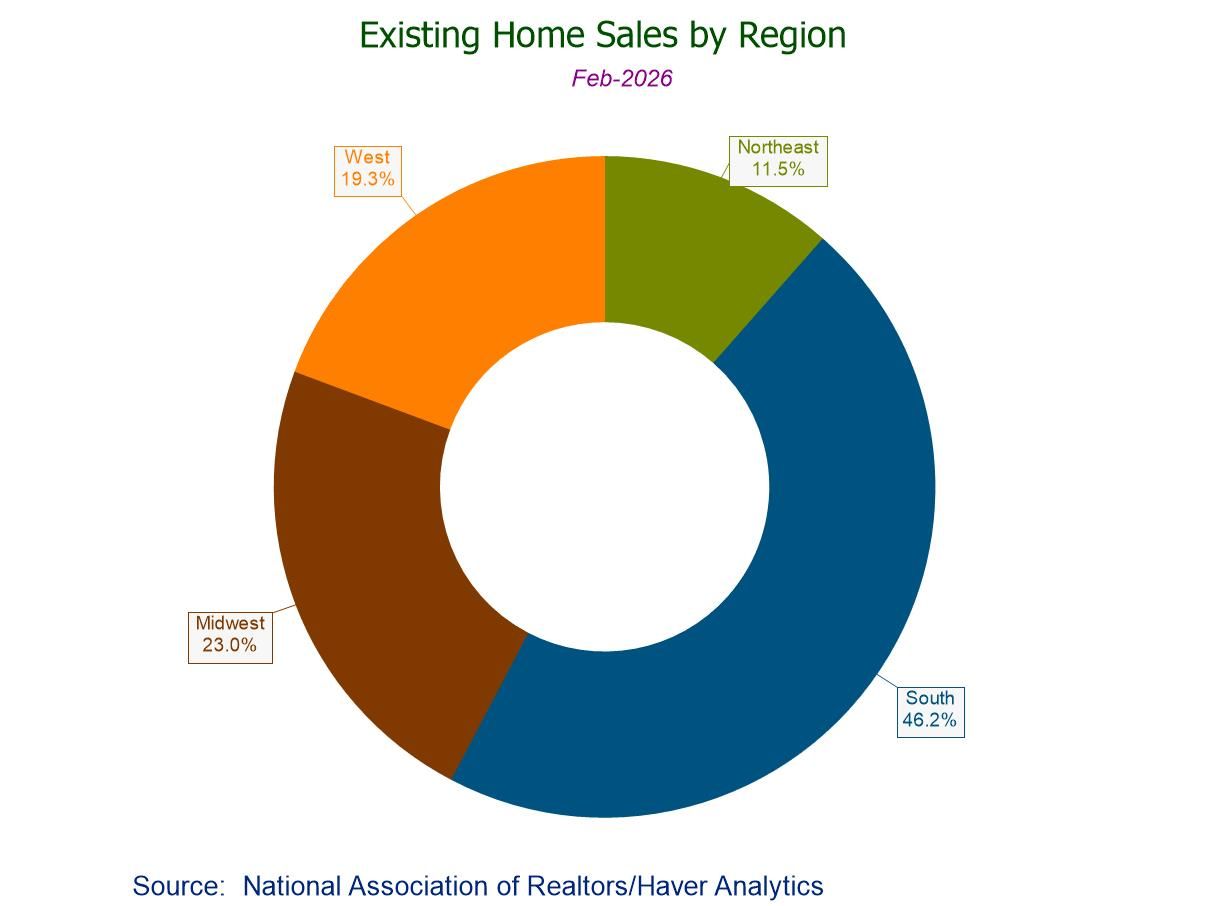

- February sales +1.7% to 4.09 mil.; -1.4% y/y, fourth straight y/y decline.

- Sales m/m up in the West (+8.2%), South (+1.6%), and Midwest (+1.1%), but down in the Northeast (-6.0%).

- Median sales price +0.8% (+0.3% y/y) to $398,000, first m/m increase since October.

- Unsold inventory +2.4% (+4.9% y/y) to three-month-high 1.29 mil. units; 3.8 months' supply.

- USA| Mar 10 2026

U.S. Existing Home Sales Unexpectedly Rebound in February

- Germany| Mar 10 2026

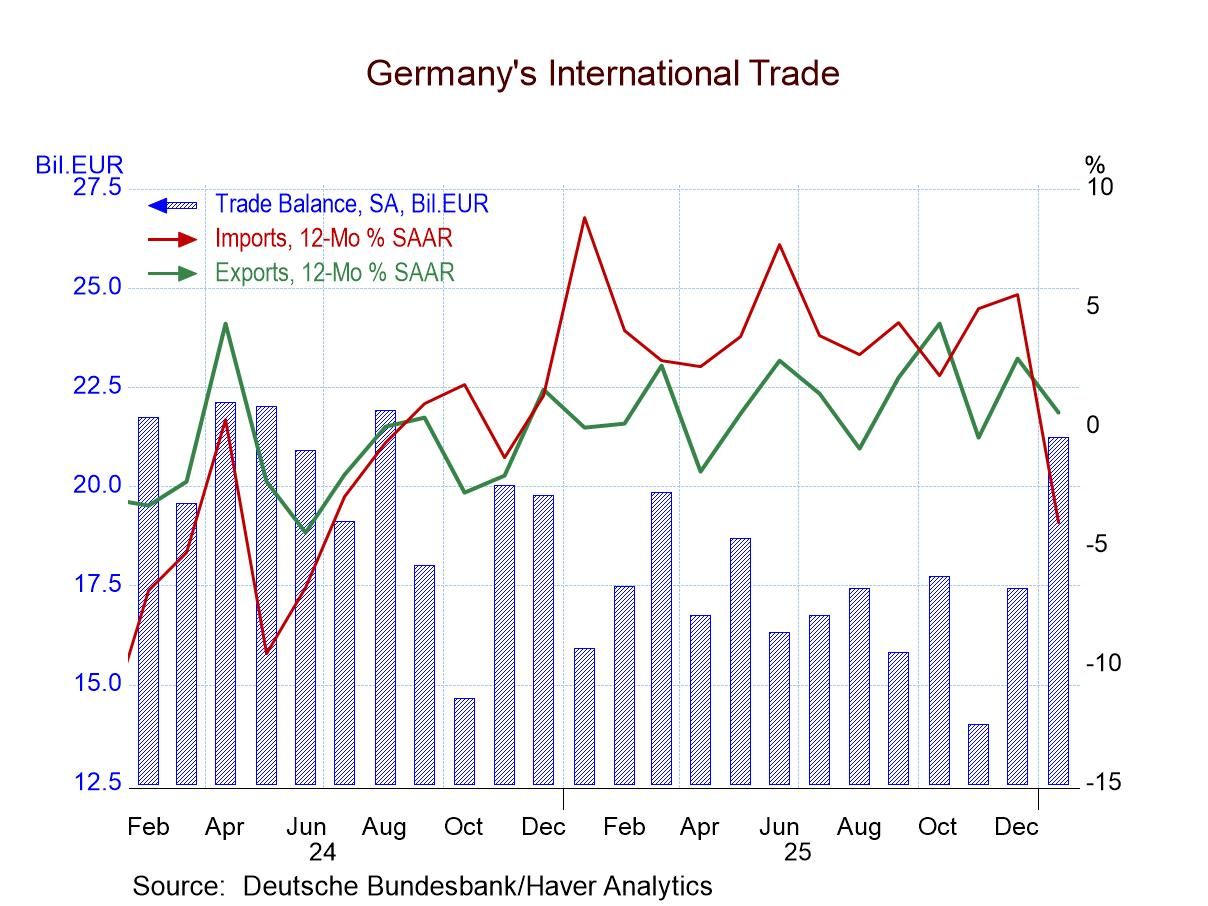

German Exports and Imports Slide in January; Sharp Import Drop Boosts Surplus

German trade flows weakened in January, with imports dropping 5.9% month to month and exports falling 2.3%. With both flows falling sharply and imports dropping at more than twice the rate of exports, the trade surplus in the month ballooned to €21.2 billion from €17.4 billion in December.

The progression of nominal growth rates for exports shows the slowing from 0.6% over 12 months to 0.3% over six months to -3.1% at an annual rate over three months. The import decline is weaker and is gathering even more downward momentum, with imports falling 4% over 12 months, dropping at a 7.4% annual rate over six months, and reaching a 15% annualized decline over three months.

Measured in real terms, exports fell by 2.9% in January as imports fell by 6.8%. The sequential growth rates for German exports and imports both show progressive deterioration, with imports weakening faster than exports. This trend is worrisome because it says that the nominal weakness is not just because of what prices are doing. Weak imports usually indicate weak domestic demand; for Germany, that could be a really bad signal. In addition, because Germany exports so much to other EMU nations, German export weakness raises questions about demand strength among fellow EMU members - and about global demand in general.

Lagged trends Lagged results give us a look into export and import trends with a one-month lag. As of December, both exports and imports still rose month-to-month. Sequential export growth was steadily accelerating, while sequential import growth rates were already decaying. German consumer goods exports were accelerating sequentially, and the ‘other exports’ category is not on its own acceleration path, but the category remains strong.

For imports, the overall nominal flows were decelerating from 12-months to 6-months to 3-months. Capital goods and motor vehicle imports both showed sequential weakening. Consumer goods imports were oscillating but still generally strong. Other imports were on a recent accelerating path, switching from negative 12-months growth to a 1% gain over six months and a 4% pace of increase over three months.

Summing up On balance, German trade trends show a lot of weakness. Much of it seems to have welled up in January ahead of the new Middle East conflict. Right now, German economic data and diagnostic trade data are not sending out good signals about the German economy.

- Germany| Mar 09 2026

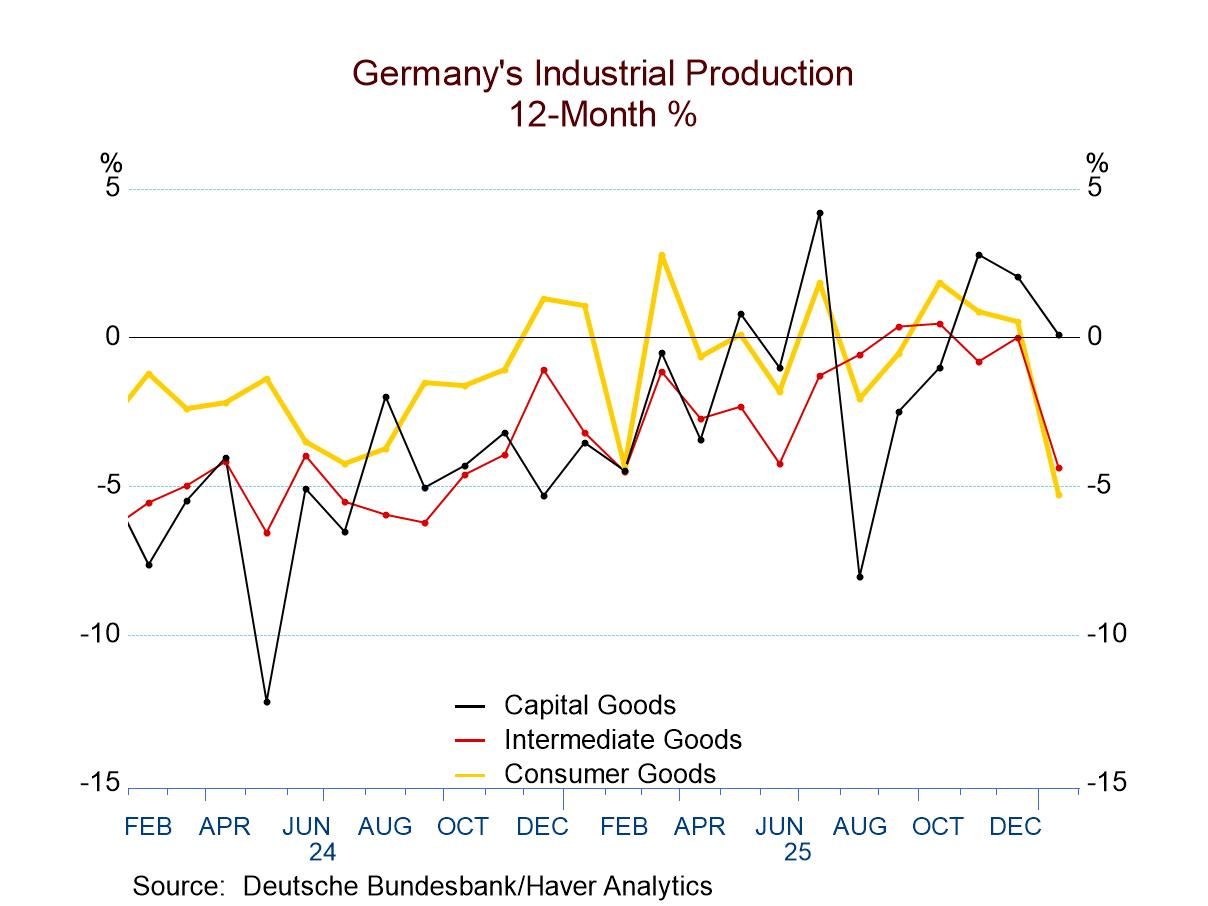

German Output Trends in January Break Lower

The German industrial sector falters German industrial output in January fell for the second month in a row; it has a sequential pattern of growth rates becoming progressively weaker from 12-months to six-months to three-months. This is not a good pattern or development. Orders also fell sharply in January, dropping by 11.1% month-to-month. At least the orders progression is not as clearly negative as it is for industrial output, but over three months real manufacturing orders are declining at a 1.8% annual rate even though the 12-month and six-month growth rates of orders still show solid positive growth results.

These data are up-to-date through January, so they do not contain any effects of the new conflict in the Middle East.

Sequential output trends German industrial output trends show progressively weaker numbers from 12-months to six-months to three-months. Consumer goods output and intermediate goods output show progressively weaker sequential results. Capital goods output shows a skinny rise of 0.1% over 12 months, a 6.6% decline at an annual rate over six months, and then a lesser pace of decline of 2.8% over three months. Capital goods output is not getting progressively weaker; however, it has been weakening and the trend is disappointing.

German survey results are less dire Other indicators of German industrial activity generally show improved monthly results. All four of the metrics in the table show improved survey values in January compared to December, but December had showed weakness relative to November across the board for those 4 metrics. The message from progressive averages in the table, from these other indicators, is that not much has changed that would allow us to discriminate strongly among activity performances reported over 12 months, six months, or three months. In the end, the three-month values are generally slightly stronger than the 12-month values, but not in a way that looks significant, and even that result does not hold for the ZEW current index.

Industrial production in other Europe Industrial production trends for other European reporters show declines in output in January of a fairly substantial magnitude in Spain and in Ireland, against strong increases in Portugal, Sweden, and Norway, and the more modest increase in France. IP in January shows cross-currents and a good deal of extremism in other Europe. The progressive trends for manufacturing production show Spanish and Irish trends deteriorating sharply from 12-months to six-months to three-months France and Portugal report uneven results that do not clarify what the underlying trend is doing. However, in northern Europe, Sweden and Norway are showing sharply accelerating growth from 12-months to six-months to three-months.

Quarter-to-Date (as of January) In the quarter to date, German manufacturing output is falling overall and for all its major components. German real manufacturing orders are falling at a 30.3% annual rate in the quarter to date, which is a nascent statistic since only January data are available now. The other industrial indicators show positive trends for most measures, with the IFO manufacturing expectation being the exception, as it weakens. Industrial production for other Europe shows sharp quarter-to-date declines in Spain and Ireland, with extremely strong quarter-to-date results in Sweden and Norway; there is strong performance from Portugal and a solid increase from France.

- USA| Mar 06 2026

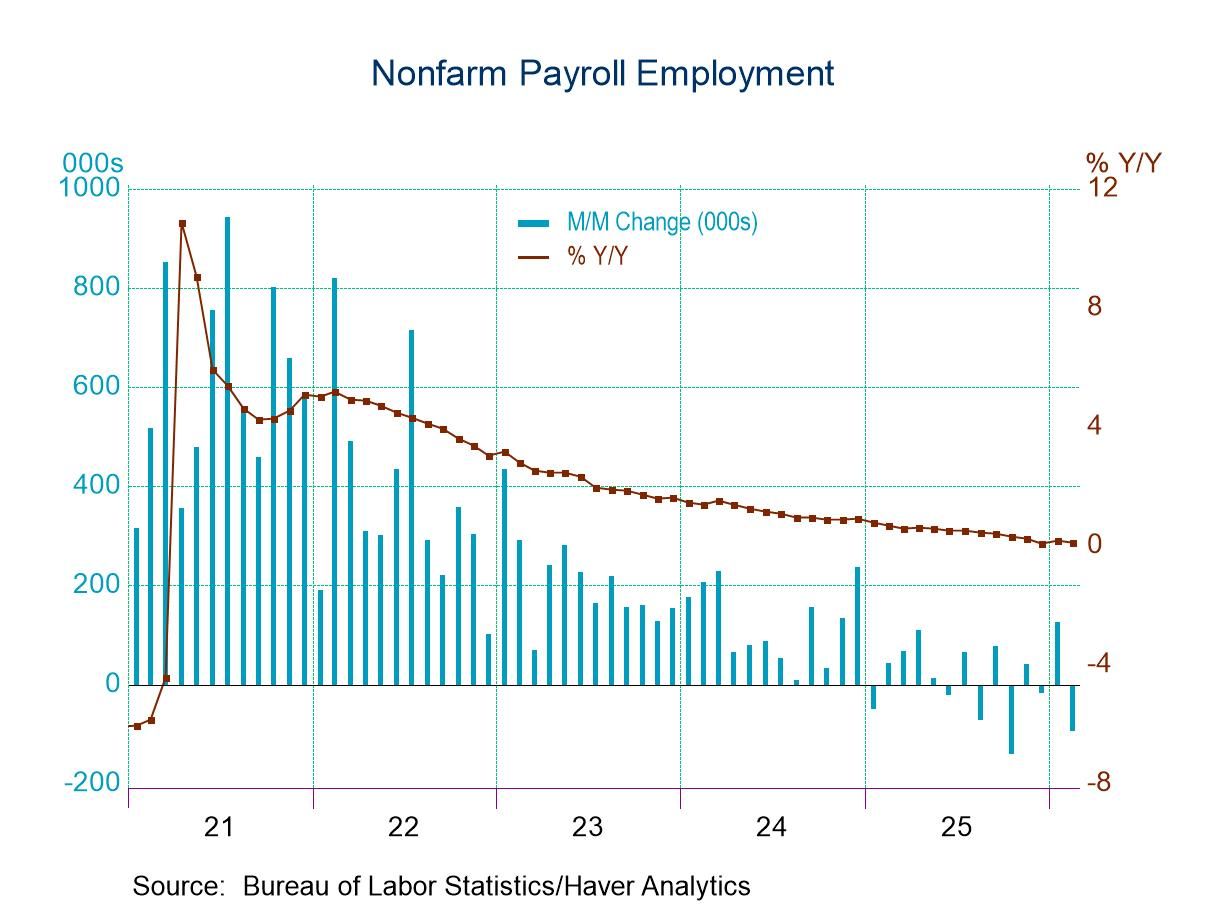

U.S. Employment Unexpectedly Fell in February

- Nonfarm payrolls fell 92,000 in February with downward revisions to both December and January

- Private sector payrolls fell 86,000 in February.

- Average hourly earnings annual growth increased to 3.8% from 3.7% in both December and January.

- Unemployment in the household survey increased 203,000, pushing the unemployment rate up to 4.4% from 4.3% in January.

- The delayed population adjustment to the household data was a very large negative as had been expected given the observed declines in immigration.

by:Sandy Batten

|in:Economy in Brief

- USA| Mar 06 2026

U.S. Retail Sales Decline in January After Flat December

- Total retail sales -0.2% (+3.2% y/y) in Jan.; 0.0% (+2.4% y/y) in Dec.

- Ex-auto sales flat for a second month (+3.9% y/y); auto sales -0.9% (+0.1% y/y), third m/m fall in four months.

- Declines m/m: gasoline stations (-2.9%), clothing stores (-1.7%), sporting goods (-1.2%), electronics stores (-0.6%).

- Gains m/m: misc. stores (+2.0%), nonstore sales (+1.9%), furniture stores (+0.7%), bldg. materials (+0.6%).

- Norway| Mar 06 2026

Norway: Output Advances in January

Industrial output in Norway rose by 1% in January after gaining 0.9% in December. Utilities output rose briskly, mining and quarrying output rose extremely sharply, while manufacturing output showed its second decline in a row.

The sequential growth rates show that the headline series for industrial production is decelerating, with nearly 7% growth over 12 months, nearly 5% growth over six months, and the growth over three months is down to zero.

On that same progression, utilities output has accelerated from 12 months to six months to three months, while mining and quarrying has a more complicated pattern—rising 1.5% over 12 month, falling at a 3.8% pace over six months, then rising at a 9.2% annual rate over three months.

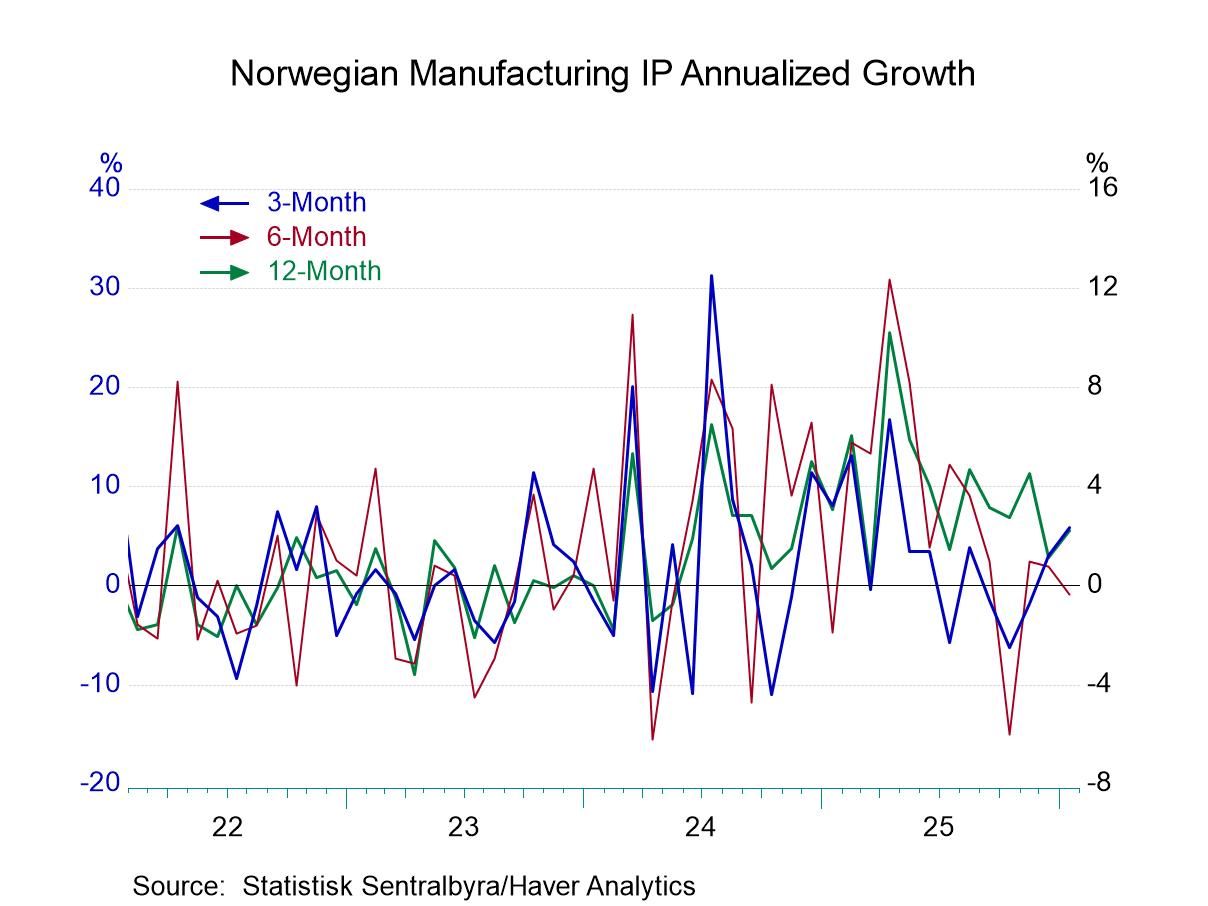

In manufacturing, the trends are also complicated but with an upbeat ending. Manufacturing output is up by 2.2% over 12 months; the growth rate shows a decline, falling at a 0.4% annual rate over six months, with output then picking up and growing at a 5.9% annual rate over three months. Despite the setback in the middle, manufacturing has a positive year-over-year growth rate and shows strength over three months. This pattern is followed by food and also by textiles, with the exception that textiles are still showing a year-over-year decline of 0.9%. However, textile output is now growing briskly at a 7.4% annual rate over three months.

Norway is also experiencing a pickup in inflation. Its HICP inflation rate is 3.5% over 12 months, stays pretty much there with a 3.4% annual rate over six months, and then jumps up to a 4.9% annual rate over three months. However, that acceleration is tempered by a core inflation rate that is unchanged at 3.2% in each horizon. These growth rates are still excessive, with the central bank having a target of 2%; however, the inflation rate isn't getting any worse.

The industrial pattern for Norway is somewhat complicated by the fact that the headline measure for industrial production is showing a clear deceleration, while manufacturing is showing a more complicated pattern with some near-term acceleration over three months.

And for the quarter to date, which is a nascent comparison since the data are only available through January, we have overall industrial production growing at a 2.7% annual rate and manufacturing growing at a 2.2% annual rate. The quarter also shows inflation flying at a 3.9% annual rate, although core inflation is more tempered at a 2.6% annual rate pace.

- USA| Mar 05 2026

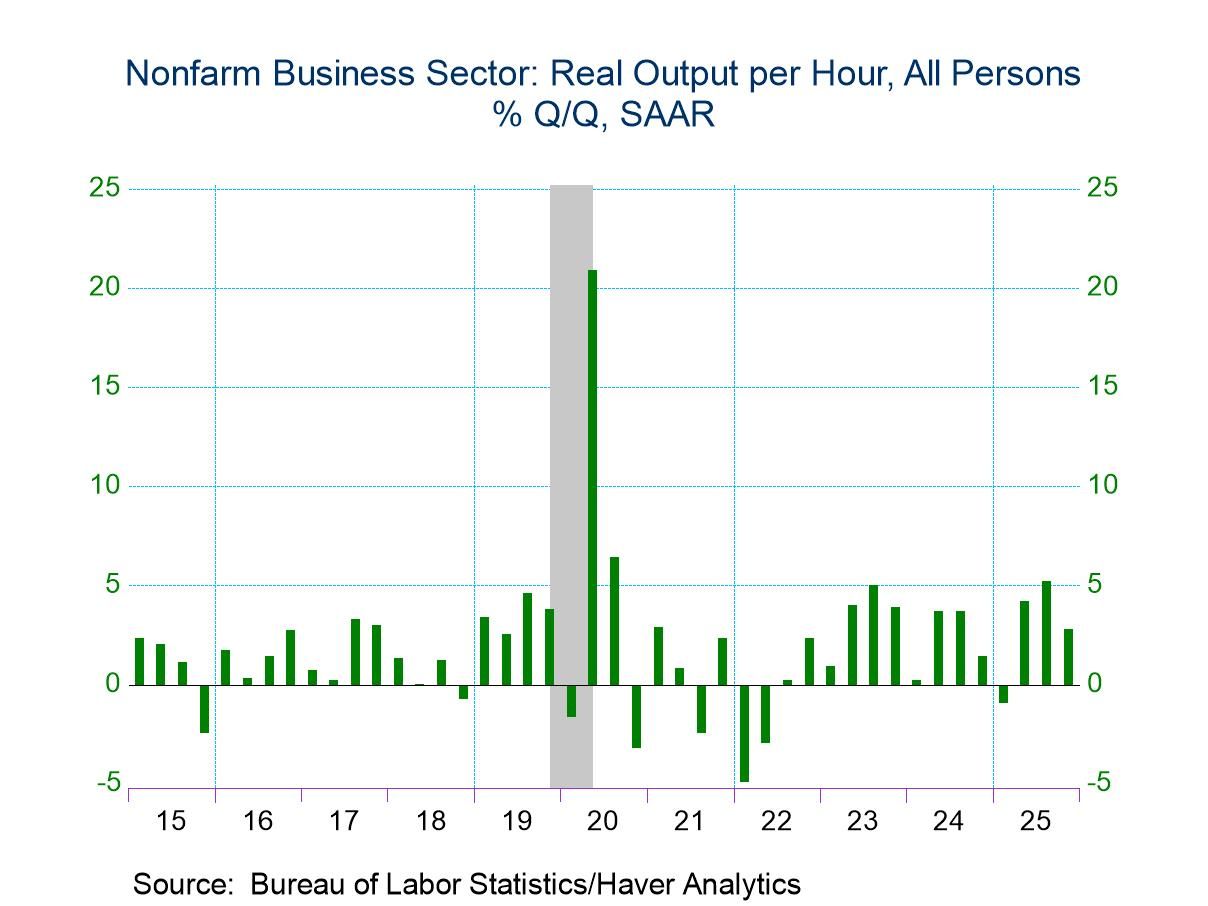

U.S. Productivity Increases More than Expected in Q4

- Nonfarm business output per hour rose 2.8% q/q SAAR in Q4 on top of an upward revision to Q3.

- Compensation jumped 5.7% q/q in Q4 resulting in a 2.8% quarterly increase in unit labor costs.

by:Sandy Batten

|in:Economy in Brief

- USA| Mar 05 2026

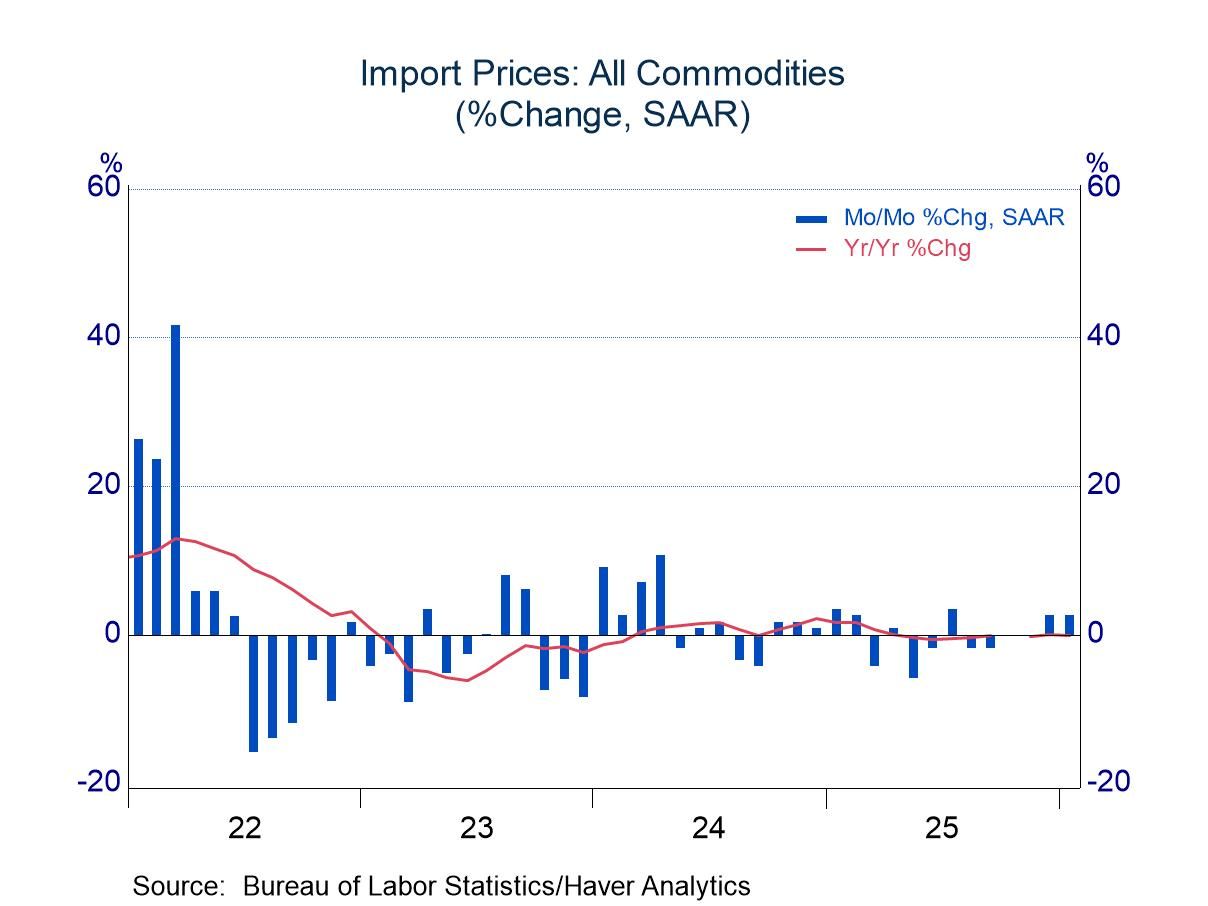

Export and Import Prices: Upward Pressure Points in January

- Nonpetroleum import prices break from a flat trend with jumps in both December and January.

- Export prices also accelerate, led by consumer goods and capital goods.

- of2702Go to 2 page